Midbrain syndromes

Alternating midbrain syndromes

1.1. Weber's syndrome. The clinical picture was first described by O. Gendren in 1838. Later it was described in the works of A. Gübler (1856), G. Weber (1863) and E. Leiden (1876). The eponymous name “Weber syndrome” was proposed by J. Grasse in 1900. It occurs with a lesion in the area of the base of the cerebral peduncle in the basal region, where the corticospinal and corticonuclear tracts pass, as well as the intrastem region of the oculomotor nerve root (Fig. 19).

Rice. 19. Scheme of localization of lesions in Weber syndrome.

The clinical picture of Weber syndrome consists of the presence of signs of paresis of the oculomotor nerve (complete ptosis of the upper eyelid, mydriasis with loss of photoreaction of the pupil, divergent strabismus, diplopia, absence of upward, inward and downward movements of the eyeball, paresis of accommodation and convergence) on the affected side with contralateral spastic hemiplegia/ hemiparesis. When the lesion is extensive and involves the optic tract or the external geniculate body (more often with an aneurysm of the posterior cerebral artery), contralateral homonymous hemianopia is added to these symptoms.

With incomplete damage to the third pair, either only the internal or only the external muscles of the eye can be involved, and sometimes only individual muscles. When the external muscles are affected, the eye deviates towards the temple and “looks” towards the pathological focus in the brain, “turning away” from the paralyzed limbs.

Most often, Weber syndrome is caused by infarction or hemorrhage in the paramedian perforating branches of the terminal basilar artery or peduncular perforating branches of the posterior cerebral artery. It may also be caused by a space-occupying process at the base of the cerebral peduncle or in the temporal lobe, with dorsal spread of a tumor of the pituitary region, or basal meningitis.

1.2. Benedict's syndrome (syn.: red nucleus syndrome) was first described by the Austrian therapist and neurologist M. Benedict in 1889. It occurs when the tegmentum of the midbrain is damaged, involving the red nucleus, which is affected only in the dorsal part, with the capture of the fibers of the third pair of roots passing through it. , substantia nigra, dentarubral tract (Fig. 20).

Rice. 16. Scheme of localization of lesions in Benedict syndrome.

The clinical picture of Benedict's syndrome consists of signs of complete or partial damage to the oculomotor nerve on the affected side; extrapyramidal hyperkinesis (hemichoreoathetosis) and cerebellar symptoms (intentional hemitremor) are observed contralaterally; mild spastic hemiparesis is possible.

Benedict's syndrome occurs in circulatory disorders in the basin of the paramedian perforating branches of the terminal basilar artery or peduncular perforating branches of the posterior cerebral artery, meningovascular syphilis, solitary tuberculomas, tumors of the cerebral peduncles.

1.3. Claude's syndrome (syn.: inferior red nucleus syndrome) was described by the French neurologist and psychiatrist A. Claude together with the histologist M. Loyer in 1912. Topically, the lesion is located in the tegmentum of the midbrain involving the nucleus of the oculomotor nerve, the dorsal part of the red nucleus (Fig. 21).

Rice. 21. Scheme of localization of lesions in Claude syndrome.

The clinical picture of Claude's syndrome is characterized by a combination of damage to the oculomotor nerve on the affected side with extrapyramidal and/or cerebellar symptoms on the side opposite to the lesion.

1.4. Monakov syndrome (syn.: anterior choroidal artery syndrome) was described by the Swiss neurologist K. Monakov in 1928. It is characterized by damage to the oculomotor nerve, extrapyramidal formations (red nucleus, caudate nucleus, subthalamic nucleus of Lewis), structures of general sensitivity (medial lemniscus, thalamic nuclei) , less often the pyramidal tract and the lateral geniculate body are involved (Fig. 22).

Rice. 22. Scheme of localization of lesions in Monakov syndrome.

In the clinical picture of Monakov syndrome, damage to the oculomotor nerve (complete or partial) is observed homolaterally, on the side opposite to the lesion - extrapyramidal hyperkinesis (hemichoreoathetosis, less often - hemiballismus), hemihypesthesia of superficial and/or deep sensitivity, often without facial involvement, homonymous hemianopsia, hemiparesis or hemiplegia .

The causes of Monakov syndrome are ischemic strokes in the anterior choroidal artery basin, less often - with gliomas of the trunk and other organic processes.

1.5. Bielschowsky's syndrome was described by the German ophthalmologist A. Bielschowsky in 1914. This mesencephalic syndrome occurs when the lesion is localized at the level of the nucleus of the trochlear (IV) nerve and the pyramidal tracts (Fig. 23).

Rice. 23. Scheme of localization of lesions in Bielschowsky syndrome.

The clinical picture consists of damage to the trochlear nerve in the form of mild converging strabismus, double vision when looking down on the side of the lesion with alternating hemiparesis/hemiplegia.

2. Quadrigeminal syndrome (syn.: midbrain roof syndrome). Occurs when the superior and inferior colliculi of the midbrain, lateral lemniscus, nuclei of the third pair of cranial nerves and periaqueductal gray matter are affected (Fig. 24). Most of the listed structures are affected secondarily, as a result of compression during pathological processes in the quadrigeminal tract or adjacent areas (pineal gland, third ventricle, thalamus, cerebral peduncles, cerebellum).

Rice. 24. Scheme of localization of lesions in quadrigeminal syndrome.

Quadrigeminal syndrome is characterized by a triad of symptoms:

1) Oculomotor disorders in the form of paresis of gaze up and down, divergent strabismus, ptosis, mydriasis, vertical nystagmus

2) Impaired coordination (contralateral cerebellar ataxia due to damage to the superior cerebellar peduncle and red nucleus)

3) Bilateral hearing loss, predominant on the side opposite to the lesion due to damage to the inferior colliculi and/or the lateral lemniscus system.

3. Parinaud's syndrome (syn.: vertical gaze palsy syndrome, supranuclear palsy) was described by the French ophthalmologist A. Parinaud in 1886. It is a variant of the quadrigeminal syndrome and occurs with bilateral processes at the level of the superior colliculus, the upper part of the posterior longitudinal fasciculus and the posterior commissure (Fig. 25).

Clinically, Parinaud's syndrome is characterized by the appearance of vertical paresis of gaze (usually upward, less often downward), paresis of convergence of the eyeballs with, as a rule, preserved horizontal conjugal eye movements, often bilateral miosis (or mydriasis) with the absence/dissociation of the photoreaction, reaction to convergence and accommodation; when trying to look up, converging or vertical nystagmus appears. Often there is partial bilateral ptosis of the upper eyelids, pathological retraction of the upper eyelids (the position of the upper eyelid in which a white strip of sclera is visible between the edge of the eyelid and the limbus of the cornea when looking straight) or lag of the upper eyelids (the same phenomenon when looking down), sometimes an imbalance.

Rice. 25. Scheme of localization of lesions in Parinaud syndrome.

The causes of Parinaud's syndrome are similar to quadrigeminal syndrome, most often of secondary dislocation origin in tumors of the quadrigeminal, pituitary region or pineal gland, strokes, brainstem encephalitis (including epidemic Economo encephalitis), neurodegeneration (progressive supranuclear palsy), hydrocephalus.

4. Körber-Salus-Elschnig syndrome (syn.: aqueduct of Sylvius syndrome) was described by the French ophthalmologist A. Parino in 1883, and by the German ophthalmologist G. Körber in 1903. Associated with damage to the gray matter surrounding the cerebral aqueduct. Manifested by retraction and trembling of the eyelids, anisokaria, convergence spasm, vertical gaze paresis. Is a sign of a tumor process with compression of the Sylvian aqueduct

5. Opsoclonus syndrome ("dancing eyes" syndrome) occurs when the posterior longitudinal fasciculus is damaged at the level of the midbrain, which has the nature of irritation, as well as the cerebellar-stem connections - the dentorubro-olivary tracts (Fig. 26).

Rice. 26. Scheme of localization of lesions in opsoclonus syndrome.

Clinically, it is manifested by hyperkinesis of the eyeballs in the form of friendly, fast, jerky movements, irregular in amplitude, usually in the horizontal plane. A disorderly change of horizontal, vertical, diagonal, circular and pendulum-like movements of different frequencies and amplitudes is possible. The direction of opsoclonus changes quickly and suddenly, the intensity increases with gaze fixation and voluntary eye movements. Opsoclonus persists during sleep and worsens upon awakening. Opsoclonus is often mistaken for nystagmus, which is distinguished by the presence of two phases: slow and fast. A combination of opsoclonus with generalized myoclonus (opsoclonus-myoclonus), ataxia, intention tremor, hypotension, etc. is possible.

Opsoclonus occurs in viral encephalitis, multiple sclerosis, tumors of the brainstem and cerebellum, paraneoplastic syndromes (especially in children, in the form of opsoclonus-myoclonus), trauma, metabolic and toxic encephalopathies.

6. Hertwig-Magendie syndrome was described by the French physiologist F. Magendie in 1833, and later by the German biologist R. Hertwig in 1926. Hertwig-Magendie syndrome is associated with unilateral damage to the cerebral peduncle, disconnection of the connections of the medial longitudinal fasciculus, which is observed more often in cranial trauma, brainstem stroke, midbrain tumors. It manifests itself in different vertical positions of the eyeballs: on the affected side the eye is deviated downward and slightly inward, on the healthy side - upward and outward (Fig. 27). This syndrome is a type of so-called “oblique deviation” - vertical divergence of the eyeballs, not associated with damage to any extraocular muscle or muscle group.

Rice. 23. Hertwig-Magendie syndrome (damage to the cerebral peduncle on the right - on the affected side the eyes are deviated downward and inward, on the opposite side - upward and outward).

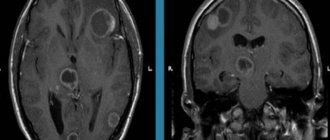

7. Decerebrate rigidity. This syndrome was first described by C. Sherrington in 1895; detailed clinical manifestations were described by D.S. Footer in 1948 Decerebrate rigidity occurs when the lesion is localized just above the vestibular nerve nuclei, which leads to disconnection between the pons and the overlying brain structures. Decerebrate rigidity is a common manifestation of severe TBI and indicates compression of the brain, i.e. on the development of dislocation syndrome due to hematoma of the posterior cranial fossa, extensive hemispheric and intraventricular hematomas, and cerebral edema. The severity of disturbances in vital functions, oculomotor disorders, the depth of paresis, and the state of muscle tone are of prognostic significance.

The main clinical manifestations of decerebration are paroxysmal tonic extension of the upper and lower extremities (hyperextension and hyperpronation), throwing back the head, clenching the jaws, and arching the back. The forearms are pronated, the hands, feet and fingers are bent (Fig. 28). Along with muscle rigidity, patients experience tonic neck reflexes, disturbances of consciousness and speech, anxiety, violent laughter and crying, breathing and sleep disorders, in some cases, impaired thermoregulation and pyramidal disorders, as well as hyperkinesis. Decerebrate posture can occur spontaneously or in response to an external stimulus (light, noise, painful stimulation).

Rice. 28. Decerebrate rigidity.

Decerebrate rigidity syndrome is observed with severe traumatic brain injury, hemorrhages in the tegmentum of the midbrain, any dislocation syndromes, and less often with severe metabolic disorders.

Middle cerebral artery syndrome

Conservative therapy

Standards of medical care require hospitalization of the patient within 1-1.5 hours from the onset of symptoms, which makes it possible to carry out treatment in the first 3-4 hours and minimize necrosis of nervous tissue. When the middle cerebral artery is damaged, patients receive complex therapy, which includes 2 main areas:

- Basic treatment

. To support vital functions, correction of blood pressure and cardiac activity, respiratory support (ventilation if indicated), infusion therapy and normalization of glycemia are recommended. - Differentiated treatment

. The “ischemic cascade” is blocked by prescribing systemic thrombolytic therapy, antiplatelet medications, and correcting the level of intracranial pressure. It is advisable to administer neuroprotectors and neurometabolites.

If there are complications, their specific treatment is provided. To correct neurological pain, antidepressants and anticonvulsants are used; for psychomotor agitation, benzodiazepines and anesthesia drugs are used. To provide nutrition for dysphagia, patients are given a nasogastric tube. Given the prolonged bed rest and immobility of patients, adequate prevention of bedsores is necessary.

Surgery

Since the options for drug thrombolysis are limited, for injuries at the level of the truncus arteriosus, some patients are prescribed interventional treatment. Mechanical thrombectomy is performed during cerebral angiography within 8 hours from the manifestation of the syndrome. If complications occur, surgical decompression of the brain may be required.

Rehabilitation

For the maximum possible restoration of neurological functions after suffering from the syndrome, the patient requires the help of a multidisciplinary team of specialists: physical therapy doctors, speech therapists, psychologists, and nurses. Rehabilitation begins early, immediately after relief of acute circulatory disorders, which has a beneficial effect on the long-term prognosis of the disease.

In order to restore range of motion in paretic muscles, electrical stimulation, acupuncture, electrophoresis are prescribed, and various areas of kinesiotherapy are used depending on the patient’s condition. To reduce emotional and volitional disorders, individual and group sessions with psychologists are recommended. Patients who have partially retained their ability to work benefit from occupational therapy with elements of vocational guidance.