Diagnostics

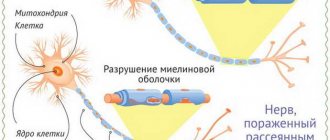

To determine multiple sclerosis, doctors use interviews and neurological examinations, and then confirm the diagnosis with MRI studies and tests.

MRI scans the brain and spinal cord for old and new lesions. For better visualization of fresh plaques, contrast is used. The diagnosis is made if the patient has 4 or more foci of demyelination measuring at least 3 mm, or 3 foci near the lateral ventricles, in the brain stem, cerebellum or spinal cord. In addition to MRI, the following may be prescribed for multiple sclerosis:

- regular blood tests to determine the level of immunoglobulins in the cerebrospinal fluid;

- lumbar punctures to study the composition of the spinal cord fluid.

How to stop multiple sclerosis: treatment of different forms of the disease

Unfortunately, despite progress in MS therapy, it is not yet possible to completely defeat the disease. However, if a person has multiple sclerosis, treatment can help reduce symptoms and reduce the number of relapses. Therapy is prescribed depending on the severity of the disease.

For progressive forms of MS, treatment can help reduce the severity of the disease. Specialists can prescribe:

- plasmapheresis - purification of the patient's blood;

- immunosuppressants - drugs that artificially suppress the immune system;

- immunomodulators are medications that regulate the body's immune response.

To prevent relapses, B-interferons can be used, and to reduce the intensity of symptoms, the following are used:

- vitamins E and B complexes;

- nootropics that improve brain activity;

- anticholinesterase drugs that inhibit the activity of the nervous system;

- muscle relaxants that help reduce muscle tone;

- enterosorbents that help remove toxins.

Rehabilitation for multiple sclerosis

- Physiotherapy.

Exercise therapy helps improve a person’s condition with impaired motor activity. Working out on exercise machines helps restore coordination of movements. With correctly selected loads, the method demonstrated excellent efficiency. - Physiotherapy.

For patients with MS, electrophoresis, myostimulation, ultrasound, and magnetic therapy are recommended. These techniques help to activate the body's metabolic processes and reduce inflammation. - Massage.

For multiple sclerosis, this rehabilitation method can be used to relieve pain symptoms and spasms. Massage also helps improve muscle tone when it decreases.

Rehabilitation for multiple sclerosis also includes psychotherapy, which will help the patient cope with negative thoughts, as well as consultations with a nutritionist.

Disease prognosis

Multiple sclerosis is not considered a fatal disease; the unpleasant symptoms of MS can be quite successfully treated. Scientists have found that thanks to modern treatment, the life expectancy of patients today has increased significantly compared to those who fell ill even a few decades ago.

Overall, people with multiple sclerosis live on average 7 years less than the general population. Often, a decrease in life expectancy is associated with complications of other pathologies: cancer and cardiovascular diseases. For many patients, quality treatment can prevent a decline in quality of life and productivity. According to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, ⅔ of people with MS are wheelchair-free even 20 years after diagnosis.

Disability in multiple sclerosis

| If multiple sclerosis has caused disability for 5 months or more within a year, the patient can apply for disability registration. |

After reviewing the documents, the commission will make a decision on incapacity for work, which gives the right to receive a pension and preferential working conditions. The establishment of a disability group is influenced by:

- the period for which the ability to work was lost;

- the period when the patient was registered with this disease;

- frequency, duration and severity of exacerbations;

- therapy results;

- changes in the course of the disease, the rate of development of symptoms.

Disability is assigned for a year, after which it is necessary to pass the commission again. Disability of groups I and II with MS gives the right to a reduced working day - 35 hours per week. In this case, wages are paid in full.

Post-stroke depression

Modern medicine sees an important role in reducing mortality and disability from stroke in primary, secondary prevention and also in effective rehabilitation after stroke, where the participation of the patient himself can hardly be overestimated. A set of measures aimed at reducing the degree of disability in stroke patients also involves combating depression (post-stroke depression, PD) that occurs in the post-stroke period.

And it occurs in almost every third patient (in 33% of cases) who survived an acute cerebrovascular accident after 3–6 months.2 And the doctor should not forget about its negative impact on the rehabilitation process, the health of patients, and their quality of life. Moreover, there is evidence that PD provokes manifestations of concomitant mental illnesses (including anxiety disorders) and significantly worsens the survival prognosis. In patients with symptoms of PD, mortality within 15 months after a stroke is 8 times higher than in patients without symptoms, and 3.5 times higher within 10 years after the event.3,4

Clinical manifestations

In patients who have had a stroke, as a rule, depression of mild severity is observed - 77%, less often (20%) - of moderate severity ("minor depression"), "major depression" (severe form) is observed no more often than 3% cases.5 PD lasts more than six months in about half of the patients, and its duration depends on the location of the stroke (six months - symptoms persist in the vast majority of patients with a stroke in the middle cerebral artery, much less with a lesion in the vertebrobasilar system).5

With mild (or moderate) degrees of depressive disorders, the patient’s complaints are often poorly represented or hidden behind motivational (sleep and/or appetite disturbances), somatic (chronic pain) and autonomic manifestations that are not perceived by the patient as depressive, which seriously complicates diagnosis.

With more severe disorders, patients most often suffer from mood swings, fatigue, sleep disturbances, irritability, fear, or apathy. At the same time, manifestations such as anhedonia, pessimism, suicidal thoughts or attention deficit, as a rule, occur in major depressive disorder and are not characteristic of PD.

Important: in a patient who has suffered a stroke, it is difficult to determine whether the symptoms of asthenia and apathy are a consequence of depression or post-stroke neurological deficit. But PD cannot be ignored, since it significantly reduces the patient’s physical activity and quality of life,6 and also significantly increases the risk of suicide.7 This condition negatively affects the patient’s motivation to take treatment, reduces his adherence to treatment, leads to increased physical disability, poor functional outcome, which ultimately increases the likelihood of recurrent stroke and determines higher mortality. As a poor prognostic sign, PD requires timely diagnosis and treatment, which are vital for recovery and prognosis in stroke survivors.

Diagnostics

Diagnosing depressive disorders after a stroke is quite difficult: contact with the patient is difficult due to aphasia; the sadness on his face is due to weakness of the facial muscles; crying - may be associated with pseudobulbar palsy; apathy – caused by damage to the right hemisphere, etc.

Diagnostic criteria for PD:8

Three (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the week and represent a change from previous functioning:

- The patient does not communicate (eg, avoids talking) most of the day, every day, or most of the week.

- Tired every day or most of the week.

- Depressed mood that persists most of the day, every day, or most of the week, as indicated either by the patient's complaints or by other people's observations (eg, feeling sad, crying easily).

- Insomnia, waking up early, or hypersomnia every day or most of the week.

- Feeling helpless, worthless most of the day, every day or most of the week.

- Periodic thoughts about death (not just fear of death), periodic thoughts about suicide without a specific plan, a suicide attempt or a specific plan to commit suicide.

- Feeling hopeless or despair (especially about the stroke) most of the day, every day, or most of the week.

- Unreasonable irritability every day or most of the week.

Symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social interaction, occupation, or other important areas of functioning. The occurrence, development and duration of these symptoms are closely related to cerebrovascular disease. The occurrence of a major depressive episode cannot be a manifestation of an adjustment disorder with depressive mood, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, delusional disorder or other specified or unspecified spectrum of schizophrenia or other mental disorders. No manic or hypomanic episode.

It is important to screen for depressive symptoms in the acute phase of stroke (within 1 month) and, if possible, record the time of onset, characteristics, severity, and associated psychological and somatic symptoms of depression. Given the close relationship between post-stroke depression and stroke, a general assessment of the stroke, including its type, location, size, severity, and the patient's functional status, is also important.

There is no diagnosis of “post-stroke depression” in the current ICD-10. Currently, a non-psychiatrist does not have the ability to use psychiatric codes, so this diagnosis will always be a complication of a stroke.

Factors that increase the risk of PD:

- older age;9

- disability and change in status in society and family after a stroke;10

- negative life events;11

- lack of social support, low family income;12

- personal premorbid neurotic disorders and type A behavior (“workaholics”, perfectionists);13

- family history of depression.14

A history of stroke, as well as depression and other mental disorders, are all important predictors of PD. Assessment of cardiovascular risk factors is also necessary, since hypertension and angina are independent predictors of PD.15,16 Motor disability is the most severe consequence of stroke.

To assess neurological deficits, it is recommended:

- NIHSS;17

- modified Rankin scale (mRS);18

- Barthel index (BI).19

Depressive symptoms can be assessed using either self-rating scales or a medical assessment.

Among the self-assessment scales in Russia, the most popular are:

- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).20

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).20

- Center for Epidemiological Research Scale.21

Differential diagnosis

Post-stroke apathy. Differential diagnosis is quite difficult, but one can rely on the clinical features of emotional manifestations and facial expressions. Apathy is accompanied by decreased cognitive function and behavioral disturbances, while PD will be characterized by anxiety, agitation, and irritability. Patients with apathy are indifferent, have a neutral mood and usually do not experience suicidal thoughts.22,23 While people with PD show a clearly negative mood. In terms of facial expression, apathetic patients often have a flat affect and lack of eye contact, while most people with depression tend to express sadness with emotion in the eyes.23

Post-stroke anxiety. It is usually observed a month after a stroke, and its frequency increases with time.24 In most patients, PD occurs in the acute stage (in the first 30 days), its occurrence is weakly related to a previous history of depression, but rather strongly depends on the stroke itself. Post-stroke anxiety is closely related to pre-existing anxiety.24 Patients with PD are characterized by persistent depressed mood and loss of interest, accompanied by physical or mental disturbances such as restlessness, tension, and palpitations. Patients with post-stroke anxiety present with fear, tension, restlessness, irritability, or restlessness.25

Post-stroke asthenia. It is a subjective feeling of physical or mental fatigue and lack of energy. It is independent of exercise or previous activity and makes it difficult to maintain even routine activities. In PD, fatigue and loss of energy may also occur, but there will also be depressed mood.26

Post-stroke psychotic disorder. May occur at different stages of stroke and rehabilitation. This symptom complex includes hallucinations, delusions, and delirium, which interfere with functional outcome and quality of life, and is associated with poor prognosis for dementia.27

Diagnosis of PD, as already mentioned, requires a serious approach and high qualifications from a specialist. This also applies to the choice of diagnostic tool (scale, questionnaire, consultation with a psychiatrist) and the commitment to diagnose depression by doctors from a neurological or rehabilitation department. It is important that stroke patients often present with aphasia, agnosia, and cognitive impairment, which increase the difficulty of recognizing and diagnosing PD.14,28

Complex therapy of patients with PD

In complex therapy of PD, various means and methods are used that have proven their effectiveness: antidepressants, psychostimulants, electroconvulsive therapy (for drug intolerance and severe depression refractory to treatment), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive behavioral psychotherapy.4

Drug therapy. The first-line drugs of choice are antidepressants; their use is most justified pathogenetically. They not only help relieve depression, improve emotional well-being and cognitive function, but also have a positive effect on neurological outcome and long-term prognosis.4

Antidepressant treatment should be initiated as soon as stroke survivors are diagnosed with PD. The choice of antidepressant depends on the patient's symptoms of depression, side effects, especially in older adults, and interactions with other medications. Clinicians should closely monitor and evaluate response to therapy, especially early in therapy, due to the potential for adverse events. Please be aware that there is also a risk of developing a manic episode during treatment. If this occurs, the antidepressant dose should be reduced or stopped immediately and replaced with an anticonvulsant or antipsychotic.29 After 2 to 3 months of resolution of depressive symptoms, therapy can be discontinued.30

Physiotherapy. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) may be an effective and safe treatment for patients with refractory PSD.31 However, side effects (headaches, gastrointestinal reactions, dry mouth, tinnitus, seizures) limit the widespread use of this method.32

Psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Effective and helpful in socializing patients in the treatment of mild to moderate depression.33,34

Early prevention

Early prevention can reduce the incidence of PD and promote effective recovery of neurological function.35 Prophylactic use of both antidepressants, especially SSRIs, and psychotherapy reduces the risk of PD, improves daily activities and cognitive function, and reduces mortality in patients with stroke, thereby improving prognosis in patients who have had a stroke.36,37

Nursing

It is very important for patients with PD both in the acute phase and in the recovery phase.38 Psychological support is also important - it is necessary to help patients adapt to the new condition, provide comfortable sleeping conditions to ensure adequate rest.39 Physical exercise can improve emotional and physical functioning of patients, thereby improving their quality of life.40

In summary, PD is common in stroke survivors and has a significant impact on physical and cognitive outcomes. Timely diagnosis makes it possible to recognize individuals at high risk of PD. The choice of treatment depends on the patient's characteristics and general condition, severity of symptoms and side effects. Early inclusion of antidepressants in treatment promotes both physical and cognitive recovery after stroke and may improve long-term survival after stroke.14,28

Unfortunately, very often PD remains unrecognized, and only in a small number of cases (about 10%) do patients with this condition receive adequate treatment. Therefore, it is especially important that doctors are aware of PD and are able to promptly recognize this condition and properly help their patients and their loved ones.

Literature

1Kaerova E.V., Zhuravskaya N.S., Matveeva L.V., Shestera A.A. Analysis of the main risk factors for stroke // Modern problems of science and education. No. 6, 2021. URL: https://www.science-education.ru/ru/article/view?id=27342

2Hackett ML, Pickles K. Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2014 (Dec.), 9 (8), p. 1017‒25.

3Kanner A.M. Depression in neurological diseases. M.: Litterra, 2007, 159 p.

4Voznesenskaya T.G. Depression in cerebrovascular diseases // Neurol. neuropsychiatrist and psychosom. No. 2, 2009, p. 9–13.

5Skvortsova V.I., Gubsky L.V., Stakhovskaya L.V. and others. Ischemic stroke / In the book: Neurology: national guide. Ed. E.I. Guseva, A.I. Konovalova, V.I. Skvortsova. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2009, p. 593‒615.

6Jiao JT, Cheng C., Ma YJ, Huang J., Dai MC, Jiang C., Wang C., Shao JF Association between inflammatory cytokines and the risk of post-stroke depression, and the effect of depression on outcomes of patients with ischemic stroke in a 2-year prospective study. Exp Ther Med. 2021 (Sep.), 12 (3), p. 1591‒1598.

7Pompili M., Venturini P., Campi S., Seretti M.E., Montebovi F. et al. Do stroke patients have an increased risk of developing suicidal ideation or dying by suicide? An overview of the current literature. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012 (Sep.), 18 (9), p. 711‒721.

8Fu-ying Zhao, Ying-ying Yue, Lei Li, Sen-yang Lang et al. Clinical practice guidelines for post-stroke depression in China. Braz J. Psychiatry. 2021, 40 (3), p. 325‒334.

9Verdelho A., Hénon H., Lebert F., Pasquier F., Leys D. Depressive symptoms after stroke and relationship with dementia: A three-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2004, (Mar. 23), 62 (6), p. 905‒911.

10Göthe F., Enache D., Wahlund LO, Winblad B., Crisby M., Lökk J., Aarsland D. Cerebrovascular diseases and depression: epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Panminerva Med. 2012 (Sep.), 54 (3), p. 161‒170.

11Tang WK, Chan SS, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, Wong KS et al. Poststroke depression in Chinese patients: frequency, psychosocial, clinical, and radiological determinants. J. Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005 (Mar.), 18 (1), p. 45‒51.

12Townend BS, Whyte S, Desborough T, Crimmins D, Markus R et al. Longitudinal prevalence and determinants of early mood disorder post-stroke. J. Clin Neurosci. 2007 (May.), 14 (5), p. 429‒34.

13Storor DL, Byrne GJ Pre-morbid personality and depression following stroke. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006 (Sep.), 18 (3), p. 457‒69.

14Hackett ML, Yapa C., Parag V., Anderson CS Frequency of depression after stroke: a systematic review of observational studies. Stroke. 2005 (Jun.), 36 (6), p. 1330‒40.

15de Man-van Ginkel JM, Hafsteinsdottir TB, Lindeman E. et al. In-hospital risk prediction for post-stroke depression: development and validation of the post-stroke depression prediction scale. Stroke. 2013, 44, p. 2441‒2445.

16Jiang XG, Lin Y., Li YS Correlative study on risk factors of depression among acute stroke patients. Euro Rev. Med Pharmacol. Sci. 2014,18, p. 1315‒1323.

17Brott T., Adams HP, Jr., Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989, 20, p. 864‒870.

18Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. II. Prognosis. Scott Med J. 1957, 2, p. 200‒15.

19Mahoney FI, Barthel DW Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965, 14, p. 61‒65.

20Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J. An inventory for measuring depression. Erbaugh J. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961 Jun; 4, p. 561‒571.

21Radloff LS The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for reseach in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977, 1, p. 385‒401.

22Withall A., Brodaty H., Altendorf A., Sachdev PS A longitudinal study examining the independence of apathy and depression after stroke: the Sydney stroke study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, p. 264‒273.

23Ishizaki J., Mimura M. Dysthymia and apathy: diagnosis and treatment. Depress Res Treat. 2011, 2011, p. 893‒905.

24Campbell Burton CA, Murray J., Holmes J., Astin F., Greenwood D., Knapp P. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2013, 8, p. 545‒559.

25Schöttke H., Giabbiconi CM Post-stroke depression and post-stroke anxiety: prevalence and predictors. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, p. 1805‒1812.

26Staub F., Bogousslavsky J. Fatigue after stroke: a major but neglected issue. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001, 12, p. 75–81.

27Almeida OP, Xiao J. Mortality associated with incident mental health disorders after stroke. Aust NZJ Psychiatry. 2007, 41, p. 274‒281.

28Chemerinski E., Robinson RG The neuropsychiatry of stroke. Psychosomatics. 2000 (Jan.-Feb.), 41(1), p. 5‒14.

29Xu XM, Zou DZ, Shen LY, Liu Y, Zhou XY et al. Efficacy and feasibility of antidepressant treatment in patients with post-stroke depression. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021, 95, e5349.

30Hebert D., Lindsay MP, McIntyre A., Kirton A. et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: stroke rehabilitation practice guidelines, update 2015. Int. J. Stroke. 2016, 11, p. 459‒84.

31Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Tateno A, Narushima K et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as treatment of poststroke depression: a preliminary study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004, 55, p. 398‒405.

32Shen X., Liu M., Cheng Y., Jia C., Pan X. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of post-stroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J. Affect Disord. 2021, 211, p. 65‒74.

33Friedland JF, McColl M. Social support intervention after stroke: results of a randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992, 73, p. 573‒581.

34 Nicholl CR, Lincoln NB, Muncaster K, Thomas S. Cognitions and post-stroke depression. Br J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 41, p. 221‒231.

35Wang F. The influence of early prevention of post-stroke depression on the rehabilitation of patients with acute stroke. Chin J. Mod Drug Appl. 2013. 7, p. 98‒99.

36Flaster M., Sharma A., Rao M. Poststroke depression: a review emphasizing the role of prophylactic treatment and synergy with treatment for motor recovery. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2013, 20, p. 139‒150.

37Ramasubbu R. Therapy for prevention of post-stroke depression. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011, 12, p. 2177‒2187.

38Clark PC, Dunbar SB, Aycock DM, Courtney E., Wolf SL Caregiver perspectives of memory and behavior changes in stroke survivors. Rehabil Nurs. 2006, 31, p. 26‒32.

39Harris AL, Elder J., Schiff ND, Victor JD, Goldfine AM Post-stroke apathy and hypersomnia leading to worse outcomes from acute rehabilitation. Transl Stroke Res. 2014, 5, p. 292–300.

40Kang JH, Park RY, Lee SJ, Kim JY, Yoon SR, Jung KI The effect of bedside exercise program on stroke patients with dysphagia. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012, 36, p. 512–20.