For some people, little or no sleep can lead to great trouble and even death. And there is another big problem - the excessive duration of this type of rest for the body. This condition is called hypersomnia, it is characterized by severe daytime sleepiness and fairly long sleep at night.

Previously, it was believed that the norm for any person was 7 hours of sleep. But based on many years of observations, it turned out that each adult has his own individual schedule, which allows him to feel in excellent shape with a certain duration and sleep pattern.

Thus, Guy Julius Caesar slept only 3 hours a day, Alexander the Great and Napoleon - 4, Thomas Jefferson and Nikola Tesla - 2 hours, Margaret Thatcher - from 1.5 to 4 hours. The great artists Leonardo da Vinci and Salvador Dali practiced “ragged” sleep - every 4 hours all day. But Albert Einstein preferred to sleep for 10-12 hours! For these great people, such a routine was normal, but, nevertheless, sleep disturbance, in particular, its excessive duration, is a serious problem.

Classification of hypersomnia

The classification of this pathology depends on the cause of its development. Based on the etiology, the following types of hypersomnia are distinguished:

- post-traumatic;

- psychophysiological;

- psychopathic;

- idiopathic;

- narcolepsy;

- associated with respiratory dysfunction during sleep and various somatic diseases.

According to clinical features, paroxysmal and permanent hypersomnia are distinguished. A feature of the paroxysmal form of this disease will be sudden attacks of drowsiness, regardless of external factors and circumstances. The phenomenon of paroxysmal hypersomnia is often a sign of cataplexy or narcolepsy. With permanent hypersomnia, patients complain of drowsiness and constant drowsiness during the day.

Types of hypersomnia

To classify hypersomnia, the etiological principle is used. Depending on the root cause, the disorder is usually divided into:

- Idiopathic hypersomnia (psychophysiological). It affects healthy people who experience regular stress and lack of sleep.

- Pathological hypersomnia. Its causes are nervous disorders and sleep disorders.

- Narcolepsy. These are imperative cases of dreams during the day. Characterized by restless sleep and a feeling of lack of sleep, it is a chronic disorder.

- Post-traumatic hypersomnia - caused by various injuries.

- Drug-induced hypersomnia. It is provoked by taking medications that cause drowsiness.

- Iatrogenic hypersomnia. Caused by certain drugs: beta blockers, antipsychotics, antidepressants, etc.

- Psychiatric hypersomnia. It is caused by mental disorders.

- Kleine-Levin syndrome. Hypersomnia occurs in episodes and is accompanied by an increasing feeling of hunger.

Permanent and paroxysmal hypersomnia are classified according to the type of course. With the first, there is constant drowsiness and drowsiness during the day, with the second, sudden, irresistible attacks of drowsiness will appear, often forcing you to fall asleep in inappropriate places. Treatment of hypersomnia directly depends on the type of disorder and its manifestation.

Causes of hypersomnia

There are many reasons why this pathological condition develops.

Most often, the main etiological factors will be:

- various neurological, somatic, mental diseases;

- sleep phenomena (motor disorders during sleep, sleep apnea syndrome);

- traumatic head injuries;

- circadian rhythm disorder (as a result of transtemporal flights, shift work schedule);

- adverse events after taking medications;

- insomnia (insomnia), etc.

The cause of psychophysiological hypersomnia, as a rule, will be lack of sleep at night, so it can be observed in healthy people and is easily eliminated by normalizing the rhythm of life, as well as minimizing mental stress.

According to studies of the mechanism and causes of hypersomnia, it is known that most often it occurs against the background of narcolepsy. Narcolepsy often occurs as a result of an existing genetic disorder. In this case, expressive daytime drowsiness and episodes of involuntary, sort of forced, falling asleep occur.

- Quite often, hypersomnic conditions can occur due to neurological dysfunction. The most unpredictable course of increased sleepiness is the clinic of hysteria. With this disease, pathological sleep can last for a very long time, in some cases several days.

- Manifestations of hypersomnia associated with mild brain injuries are difficult to distinguish from clinical manifestations of mental disorders. Differential diagnosis consists of identifying pronounced structural changes in the brain that appear as a result of injury. The absence of such damage in hypersomnia indicates that the cause of this pathological condition will not be brain damage, but a stressful state caused by trauma.

- Another cause of hypersomnia can be depressive disorders.

- In some cases, drug therapy for various diseases becomes the cause of drug-induced hypersomnia; in particular, this form of increased drowsiness is included in the list of side effects when using some antihypertensive, hypoglycemic and psychotropic drugs.

- Insufficient duration of sleep at night against the background of insomnia, dysfunction of circulatory rhythms caused by shift work and various external factors often provokes sleep disturbances and the development of a hypersomnic state.

Based on the above, it is clear that hypersomnia has a polyetiological nature, and its diagnosis requires a systematic approach.

Causes

The alternation of sleep and wakefulness in the human body is a mechanism that is clearly regulated by processes established by nature. They occur in the cerebral cortex and subcortex, a complex neural system, and are based on complex interactions of activating and inhibitory processes.

If a failure occurs in the cycle coordination system that works like a clock (even in one section), then it leads to a disruption - braking begins to predominate. The culprits for this could be:

- severe fatigue;

- stress at work and at home, emotional shock, nervousness;

- head injuries (traumatic brain injury, etc.);

- constant “lack of sleep” that continues for a long time;

- schizophrenia or any other mental disorder;

- taking medications (tranquilizers, antipsychotics, various antihistamines or sugar-lowering drugs) or drugs;

- infectious viral diseases (syphilis of the brain, encephalitis and meningitis);

- violation (cessation) of breathing - apnea, and the accompanying oxygen deficiency

- tumors, cysts, hematomas;

- disorders in the endocrine system and related diseases (diabetes mellitus, thyroid problems);

- liver and kidney diseases;

- genetics;

- heart failure;

- hypertension;

- exhaustion of the body.

These are not all the causes of hypersomnia. Its development may be associated with moving to a new place of residence, a change in lifestyle, a vacation in a situation that is sharply different from everyday life, the birth of a child, etc.

Clinical signs of hypersomnia

The clinical manifestations of this pathology are directly related to the etiological prerequisites. However, among all the signs of hypersomnia, its main symptoms are highlighted, which are represented by periodic or stable sleepiness during the day and a long duration of sleep at night. Typically, nighttime sleep with hypersomnia takes 12-14 hours. Patients often complain of difficulty waking up, lack of response to alarm clocks, and an increase in the period from a sleepy state to full awakening. Therefore, some time after waking up, patients with hypersomnia may feel lethargic and drowsy. This condition resembles a clinic of intoxication; it is also sometimes found in the medical literature under the wording “sleepy intoxication.”

The phenomenon of daytime sleepiness, regardless of its nature, is often accompanied by a decrease in performance and attentiveness, which ultimately disrupts normal work activity, provokes a disruption in the normal rhythm of life and forces people to interrupt sleep during the daytime. Sometimes, after a daytime nap, patients may notice a relief in their general condition, but in the majority of cases, drowsiness remains the same.

How much sleep should a person sleep?

According to international criteria, the average sleep duration for an adult is between seven and ten hours a day. However, the time may vary depending on age:

- The sleep norm for children is from 12 to 15 hours;

- Sleep norm for teenagers is from 10 to 12 hours;

- for older people - at least 6 hours a day.

The optimal time to go to bed is from 9 to 11 pm with sleep duration up to 6-8 am. If you follow this regime, you don’t have to worry about your health and the correct biorhythms that will correspond to the natural environment. However, there are people with both insomnia and, conversely, with hypersomnia - when for one reason or another they cannot get enough sleep and are forced to spend much more time sleeping.

Additional symptoms

In addition to the main symptoms, there are a number of clinical manifestations characteristic of certain diseases that cause hypersomnia. For example, with narcolepsy, patients may experience irresistible drowsiness and fall asleep even at the most inopportune moments. Over time, patients begin to sense in advance the approach of these attacks of forced drowsiness and take the most comfortable sleeping positions. Symptoms of this form of pathologically increased sleepiness also include hallucinations at the moments of falling asleep or waking up and awakening cataplexy, which is characterized by atony of the muscular system, as a result of which the patient loses the ability to carry out any movements for several minutes after waking up.

Psychopathic hypersomnia is characterized by an unpredictable nature of daytime sleepiness, the features of which are determined by specific psychopathology. Sleep can be quite long, but the results of a polysomnographic study indicate that the patient’s body is not in a state of sleep, and intense wakefulness is often detected on the electroecephalogram.

The phenomenon of idiopathic hypersomnia is most often characteristic of persons from 15 to 30 years old. This form of hypersomnia is manifested by difficulty waking up, constant drowsiness, in some cases, patients experience ambulatory automatism for several seconds.

If the reticular formation is damaged, as well as with epidemic encephalitis, lethargic sleep may develop, which is continuous sleep for 24 hours or more.

Modern classification of hypersomnias, their diagnosis and treatment

The ability to maintain a level of wakefulness adequate to environmental conditions is an important function necessary for a person’s normal functioning, self-realization, and achievement of success. Violation of this function and the occurrence of pathological drowsiness can significantly reduce the quality of life and performance, have significant social consequences and lead to maladjustment. Pathological sleepiness is defined as a condition characterized by an inability to maintain a sufficient level of wakefulness during the day, accompanied by episodes of an uncontrollable need to sleep, leading to involuntary (imperative) falling asleep.

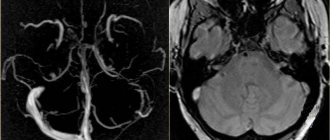

Drawing. Comparison of the representation of slow-wave sleep stages in patients with narcolepsy and healthy people

Hypersomnia is a section that includes a group of diseases that share the main symptom of excessive daytime sleepiness, not caused by disturbances in night sleep or circadian rhythms. With hypersomnia, in most cases, excessive sleepiness is a chronic symptom and must be present for at least three months before diagnosis.

Currently, according to the third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders [1], the hypersomnia section includes the following diseases:

- narcolepsy type 1;

- narcolepsy type 2;

- idiopathic hypersomnia;

- Kleine–Lewin syndrome;

- secondary hypersomnia; hypersomnia when taking medications or other drugs; hypersomnia in mental disorders;

- insufficient sleep syndrome.

As can be seen from the presented classification, hypersomnias of central origin include narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia and Kleine-Lewin syndrome. Drowsiness in other nosologies is largely secondary.

Diagnostic methods

To assess the severity of daytime sleepiness, introspective methods are used, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Stanford and Carolina Sleepiness Scales, and objective methods - multiple sleep latency test, actigraphy, polysomnography. The results of these studies do not always correlate with each other and should be subject to appropriate clinical evaluation.

The multiple sleep latency test assesses a person's ability to fall asleep in a quiet environment. Before the study, it is necessary to conduct a polysomnography, which confirms that the duration of the previous night's sleep is at least seven hours. At the end of the test, the average sleep latency is calculated, which in a healthy person usually exceeds ten minutes. For hypersomnia, the diagnostic value is a time to fall asleep of less than eight minutes. Another equally important aspect of assessing the test results is the presence of episodes of early, within less than 15 minutes, onset of REM sleep (sleep onset REM period - SOREMP). It is important to note that the presence of SOREMP can be recorded in people with chronic sleep insufficiency, circadian rhythm disorder, sleep-disordered breathing, and sometimes in healthy people (in 4–9% of cases). To diagnose idiopathic hypersomnia, long-term actigraphy and polysomnography are used with continuous recording of indicators throughout the day.

Narcolepsy

This disease from the group of hypersomnias is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness, attacks of complete or partial loss of muscle tone (cataplexy) and other phenomena associated with the REM sleep phase.

In 1880, the French physician JB Gelineau described this disease in detail and called it narcolepsy (from the Greek narke

- stupor and

lepsis

- attack). The clinical picture of narcolepsy has been well studied; the main symptoms are called the “narcoleptic pentad” [2]:

- daytime sleepiness, imperative sleep;

- daytime attacks of cataplexy; hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations;

- cataplexy of waking up and falling asleep;

- night sleep disturbances.

With narcolepsy, it is not necessary to have all of the above symptoms.

Excessive sleepiness during the day is the first and cardinal symptom of the disease, often the most disabling for the patient. Episodes of an irresistible need to sleep can occur repeatedly during the day and end with falling asleep. The duration of sleep can vary from two or three to several tens of minutes. Moreover, after waking up, most patients note some relief, but after a short time the drowsiness intensifies again. As a rule, it increases in situations that do not require the active participation of the patient, for example, when watching television, reading, or in transport. Physical activity can temporarily suppress the desire to sleep, but in some cases, drowsiness manifests itself in the form of sudden sleep attacks, which can occur, for example, while walking or while eating. Many patients with narcolepsy, due to severe drowsiness, report memory lapses, sometimes in combination with episodes of automatic behavior.

Cataplexy is a sudden short-term complete or partial loss of muscle tone while maintaining consciousness. As a rule, cataplexy occurs against the background of expressed emotions, mostly positive. Almost all patients note the occurrence of cataplexy in situations associated with fun: laughter, when telling a joke, etc. However, fear and anger can also provoke episodes. Attacks may occur at a frequency of less than one per month and more than 20 times per day. Over time, patients learn to avoid situations that provoke attacks of cataplexy, and to some extent can control their occurrence. The manifestations of cataplexy can vary significantly between patients - from rare focal attacks caused by laughter to frequent generalized attacks accompanied by falls.

Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations occur when falling asleep or waking up from sleep. As a rule, hallucinations are “holistic”, often combined with visual, auditory and tactile symptoms; they can be vivid and have a fantastic character. They are believed to reflect dream activity occurring “at the wrong time.” When they happen for the first time, they often frighten patients; over time, patients get used to them and can clearly distinguish them from real events.

Cataplexy of awakening and falling asleep (sleep paralysis) is a condition that occurs upon awakening from sleep, less often before falling asleep, characterized by the inability to make voluntary movements. In this case, the patient is fully conscious, adequately assesses the events occurring around him, but cannot move, sometimes even open his eyes. Awakening cataplexy lasts from a few seconds to several minutes and can be excruciating for sufferers. Hallucinations and sleep paralysis occur in 33 to 80% of patients with narcolepsy. They are not specific to this disorder and may appear as isolated symptoms and be diagnosed as parasomnias associated with REM sleep.

Nighttime sleep disturbance in narcolepsy is quite common. More than 70% of patients report dissatisfaction with their sleep. Falling asleep is not a problem for them, but they often complain of an inability to maintain uninterrupted sleep (frequent awakenings, difficulty falling asleep again, poor sleep quality). The time it takes patients with narcolepsy to fall asleep rarely exceeds 8 minutes; in 50% of cases, an early onset of the REM sleep phase is noted - less than 15 minutes. Compared to healthy individuals, they have an increased number of awakenings, time of wakefulness within sleep, the presence of the first stage of sleep, the number of electroencephalographic (EEG) activations, a reduced presence of delta sleep, and higher motor activity (Figure) [3]. Insomnia in narcolepsy is not a comorbid disorder, but a symptom of the disease that correlates with the severity of daytime sleepiness, reduces the quality of life of patients and requires therapy.

In addition, narcolepsy is often accompanied by other sleep disorders. Researchers from Innsbruck report that 24% of one hundred patients with narcolepsy examined using polysomnography were diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea of varying severity, and 34% were diagnosed with parasomnias (in 24% of cases - rapid eye movement sleep without atonia, and in 10 % of cases – parasomnias not associated with REM sleep). Movement disorders were observed in 55% of patients (31% had bruxism, 24% had restless legs syndrome) [4].

In addition to the main symptoms of narcolepsy, obesity (defined as a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m²), symptoms of depressive or anxiety disorders with panic attacks are diagnosed twice as often as in the general population. In 20% of cases, social phobias are identified. More than half of patients with narcolepsy report increased fatigue not associated with drowsiness.

Narcolepsy type 1

Diagnostic criteria for type 1 narcolepsy (hypocretin deficiency syndrome, narcolepsy with cataplexy) include complaints of daytime sleepiness or urgency for more than three months, and one or both of the following criteria:

1) the presence of cataplexy. When performing a multiple test, mean sleep latency is ≤ 8 minutes and two or more SOREMP episodes are recorded. In this case, an episode of SOREMP recorded during an overnight polysomnography can replace one SOREMP on a multiple sleep latency test;

2) hypocretin 1 level in the cerebrospinal fluid ≤ 110 pg/ml or

The prevalence of narcolepsy with cataplexy in different populations ranges from 0.02 to 0.18%. Both men (with a slight advantage) and women are susceptible to the disease. The onset of the disease in most cases occurs after five years, and the most typical age of onset of first symptoms is from 10 to 25 years. In young children, symptoms of narcolepsy and especially cataplexy may manifest atypically, which complicates diagnosis and increases the time to establish a diagnosis. Narcolepsy type 1 has been shown to be associated with hypocretin deficiency due to selective loss of neurons in the hypothalamus. Post-mortem examination of the brains of narcoleptics using the latest immunohistochemical antigen reconstitution methods revealed the loss of up to 90% of hypocretin neurons and their axons. The overwhelming majority (90–95%) of patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy have low levels of hypocretin 1 (

In 1999 and 2000 Reports have been published that narcolepsy may be autoimmune in nature: the immune system mistakenly attacks certain brain cells, perceiving them as foreign. 90% of patients with type 1 narcolepsy have a special variant of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene group of subtypes DR2/DRB1*1501 and DQB1*0602, but in the general population this variant occurs in 12 to 38% of cases. The proteins encoded by the genes in this region are involved in the presentation of antigens to cells of the immune system, and many autoimmune diseases are associated with one or more types of HLA genes. In 2013, the increased incidence of narcolepsy was confirmed to be associated with seasonal increases in streptococcal infections, H1N1 viral infections, and H1N1 influenza vaccinations, but definitive cause-and-effect relationships have not been established [5]. Studies have shown an increase in the number of antibodies to beta-hemolytic streptococcus, the maximum values of which occurred at the onset of narcolepsy and decreased subsequently. It has been suggested that streptococcal infection may represent an environmental “trigger” that triggers the development of the disease. However, definitive evidence of the autoimmune etiology of narcolepsy has not yet been obtained.

Narcolepsy type 2

Diagnostic criteria for type 2 narcolepsy (narcolepsy without cataplexy) are:

- complaints of daytime sleepiness or urgency to fall asleep for more than three months;

- when performing a multiple test, mean sleep latency ≤ 8 minutes, two or more episodes of SOREMP are noted. In this case, an episode of SOREMP recorded during an overnight polysomnography can replace one SOREMP on a multiple sleep latency test;

- absence of attacks of cataplexy;

- Cerebrospinal fluid hypocretin 1 was not measured or was > 110 pg/mL, or > 1/3 of the mean values of healthy individuals in the population.

It should be noted that if over time the patient develops attacks of cataplexy or at a later stage the concentration of hypocretin 1 in the cerebrospinal fluid is ≤ 110 pg/ml or

Excessive daytime sleepiness is the main symptom of type 2 narcolepsy. Although there is no cataplexy, sufferers may experience a feeling of weakness caused by strong emotions such as stress and anger. In addition, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations, automatic behavior, and nighttime sleep disturbances may occur. The prevalence of type 2 narcolepsy is 15–25% of the total number of patients with narcolepsy. The disease usually debuts in adolescence. Approximately 10% of patients develop cataplexy during their lifetime, requiring a change in diagnosis. The pathogenesis of type 2 narcolepsy is unclear. This is most likely a heterogeneous disease, but there is evidence that it may be caused by partial loss of hypocretin neurons [6].

Idiopathic hypersomnia

This disorder is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness that cannot be explained by another sleep disorder, in the absence of cataplexy and the presence of no more than one SOREMP documented on a multiple sleep latency test and previous polysomnography. The presence of somnolence should be confirmed using objective research methods: multiple sleep latency test (average sleep latency ≤ 8 minutes), 24-hour polysomnography (total sleep time ≥ 660 minutes), actigraphy. The duration of night sleep in at least 30% of patients exceeds ten hours. Sleep efficiency according to polysomnography is usually high (averaging 90 to 94%). With idiopathic hypersomnia, a prolonged and severe form of sleep inertia (sleep intoxication) is observed in 36–66% of cases, and may be accompanied by irritability, automatic behavior, confusion, the duration of this state can be an hour or more. To wake up, patients are forced to use special devices or procedures. As a rule, patients do not notice any relief after sleep and feel overwhelmed, sleepy and tired. Quite often, patients with idiopathic hypersomnia have concomitant symptoms of dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system: headache, orthostatic disorders, impaired thermoregulation, Raynaud's syndrome. Sleep paralysis and hypnagogic hallucinations occur in 4–40% of cases.

Previously, this disease was divided into two forms: with increased sleep time (≥ 10 hours) and without increased sleep time (

Idiopathic hypersomnia is currently considered a heterogeneous disease, the pathophysiology of which is not yet known. The average age of onset of the disease in different populations ranges from 16.6 to 21.2 years. Women get sick slightly more often. There is a family predisposition to the development of this disease. After the appearance of the main symptoms, the disease, as a rule, proceeds without significant fluctuations for a long time, however, in 14–25% of cases, spontaneous remissions are observed. Complications are observed mainly in the social and professional spheres: working capacity, educational performance, social status decrease, and job loss is possible.

Kleine–Lewin syndrome

Kleine-Lewin syndrome (periodic hypersomnia, periodic hibernation syndrome) is characterized by recurrent episodes of severe sleepiness associated with cognitive, psychiatric and behavioral disorders. The duration of a typical episode averages about ten days (range from 2.5 to 80 days). In rare cases, this condition can last for several weeks or months. Often the first episode is provoked by viral infections of the upper respiratory tract (less often gastroenteritis), head trauma, alcoholic excess, the effects of anesthesia, and stress. Subsequently, episodes recur on average once every three months for many years. During these periods, patients may sleep up to 16–20 hours a day, waking and rising only to eat and recover (no urinary incontinence occurs). When they wake up, they remain sleepy, lethargic, and apathetic; if they are not allowed to sleep, they become irritable. Typical are retrograde amnesia and changes in the perception of the environment (derealization). Less commonly observed are hyperphagia (66%), hypersexual behavior (53%, mostly men), depression and anxiety (53%, mostly women), hallucinations and delusions (30%). The simultaneous occurrence of all these symptoms is the exception rather than the rule. Their appearance is more typical at the beginning of the disease and during the first part of the episode. In some cases, periodic drowsiness may be the only symptom of the disease.

During an attack, social and professional functions are significantly impaired; patients are forced to stay in bed and cannot study or work. Physical examinations do not reveal any changes except for general psychomotor slowing.

Between episodes, patients look absolutely normal in terms of sleep, learning, work, mood, and nutrition. Kleine–Lewin syndrome, in which episodes of hypersomnia were associated exclusively with the menstrual cycle (occurring immediately before or during menstruation), is a condition that has been described in only 18 women. At the same time, drowsiness was combined with hyperphagia in 65%, sexual disinhibition in 29% and depressive mood in 35% of cases. The episodes lasted from three to 15 days and occurred less than three times a year. Menstrual cycle-related sleepiness may be a variant of Kleine-Lewin syndrome, although a positive response to contraceptive doses of estrogen and progesterone suggests endocrine disturbances in these cases.

Kleine–Lewin syndrome is a rare disease, with an incidence of one to two cases per million. Typically, it begins in early adolescence (81%). Risk factors for the development of the syndrome include birth injuries and perinatal pathology. Familial cases of the syndrome are observed in 5% of cases. In most cases, the disease has a benign course. Over time, there is a decrease in the frequency, duration and severity of hypersomnia episodes. Its average duration is 14 years. Male gender, onset of the disease at the age of younger than 12 years or older than 20 years, as well as the presence of hypersexuality during episodes of hypersomnia are prognostic signs of a longer duration of the disease.

The results of polysomnographic studies are difficult to interpret and depend largely on the length of recording, as well as the timing of recording relative to the onset of the hypersomnia episode and the duration of the disease. Overall, there was an increase in total sleep time to 18 hours (average 11–12 hours). During episodes of hypersomnia, the EEG showed a general slowing of background activity and frequent bilateral high-amplitude paroxysms in the range from 5 to 7 Hz.

The pathophysiology of this disease is currently unknown. Various studies: magnetic resonance imaging of the head, cerebrospinal fluid tests, determination of the concentration of hypocretin 1, hormone levels and its daily fluctuations did not reveal any significant changes. Positron emission tomography during episodes of hypersomnia showed a decrease in metabolism in the thalamus, hypothalamus, medial temporal and frontal lobes of the brain. In half of the patients, these changes persisted during asymptomatic periods. Pathological studies of patients with Klein–Lewin syndrome revealed foci of local multifocal encephalopathy in various areas of the brain. The cause of these disorders may be autoimmune, inflammatory or metabolic lesions.

Secondary hypersomnia

This is hypersomnia caused by another disease, manifested by an increase in sleep time at night, daytime sleepiness, or daytime falling asleep. Daytime sleepiness can vary in severity and be accompanied by episodes of daytime sleep that are brief and relieved, as in narcolepsy, or long and unrefreshing, as in idiopathic hypersomnia. Other symptoms such as sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations, or automatic behavior may also be present.

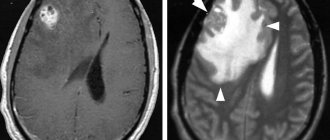

The main task in secondary hypersomnia is to establish the connection between hypersomnia and the underlying disease. Hypersomnia can occur against the background of damage to the central nervous system: metabolic encephalopathies, strokes, infections, tumors, sarcoidosis, neurodegenerative diseases, especially if they affect the hypothalamus or the rostral part of the brain. Daytime sleepiness in Parkinson's disease is considered a common symptom, but it must be taken into account that it can be caused by severe disturbances in night sleep, as well as by taking dopaminergic drugs. Secondary hypersomnia can be observed in genetic diseases: Niemann-Pick disease type C, Norrie disease, Prader-Willi syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, Moebius syndrome, Smith-Magenis syndrome, etc.

The presence of other sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea or periodic limb movement syndrome, does not exclude the diagnosis of secondary hypersomnia, but it can only be made after adequate treatment of these disorders.

Cataplexy, multiple sleep latency test recordings of two or more SOREMPs, or low hypocretin 1 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are diagnosed as secondary narcolepsy.

Hypersomnia when taking medications or other drugs

Sedation and excessive daytime sleepiness are common side effects of a large number of drugs used in medical practice, such as benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, opioids, barbiturates, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antihistamines and some antidepressants. Drowsiness can also occur while taking dopamine agonists - pramipexole or ropinirole, or, in more rare cases, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, some antibiotics, antispasmodics, antiarrhythmics and beta blockers. The most susceptible to the development of such drowsiness are elderly people suffering from comorbid diseases and forced to take a large number of medications in various combinations. The diagnosis is confirmed if symptoms resolve after stopping the drug that causes drowsiness. The diagnosis also includes hypersomnia that occurs when taking psychostimulants, amphetamines and other drugs.

Hypersomnia in mental disorders

This form of hypersomnia is characterized by complaints of drowsiness as part of the symptoms of mental illness. It most often occurs against the background of seasonal affective disorder, depression and bipolar disorder.

Hypersomnias in mental disorders account for 5–7% of all hypersomnias. Women are more often affected. The typical age for developing this condition is between 20 and 50 years. Despite the fact that patients complain of increased sleep time, no objective evidence of this has been obtained. Polysomnography revealed an increase in the time spent in bed, time falling asleep, the number of awakenings and time spent awake within sleep, and a decrease in sleep efficiency. In depression, there may be a reduction in REM sleep latency. Mean sleep latency as measured by multiple sleep tests generally remains within the normal range and contrasts with subjective complaints of sleepiness and Epworth sleepiness scores. The results of 24-hour polysomnography show a significant increase in time in bed during the day and night, and this behavior of patients can be characterized by the term “clinophilia.”

Insufficient sleep syndrome

Insufficient sleep syndrome (behaviorally induced sleep insufficiency syndrome, chronic sleep deprivation) occurs when the amount of sleep necessary to maintain a normal level of wakefulness is regularly limited. There is a significant discrepancy between the need for sleep and the duration of actual sleep. The significance of this discrepancy is underestimated by patients. The most common complaints when visiting a doctor, in addition to drowsiness, are irritability, inattention, decreased motivation and activity, lack of energy, dysphoria, fatigue, anxiety, and general malaise. A significant increase in sleep time before the weekend or on vacation compared to the work week indirectly confirms the presence of this disorder. Polysomnography and multiple sleep latency tests are not required to make a diagnosis. The diagnosis is considered proven if the symptoms regress with increasing sleep duration of the patient.

Insufficient sleep syndrome can develop regardless of gender at any age, but teenagers are more often affected. This is due to the high need of adolescents for sleep, however, social factors, the need to get up early for school, increased activity in the evening, computer, Internet, and underestimation of the importance of sleep often lead to its chronic limitation.

Treatment of hypersomnias

Therapy of hypersomnic syndromes must be carried out taking into account the etiology of the disease. In cases of a secondary nature, the main efforts should be aimed at treating the underlying (somatic, neurological or psychiatric) disorder causing drowsiness.

Currently, treatment of hypersomnias of central origin (narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, Kleine-Lewin syndrome) is symptomatic and is focused on reducing the severity of symptoms and improving the quality of life of patients. Therapy for narcolepsy includes three main areas: reducing the severity of daytime sleepiness, preventing cataplexy and improving night sleep.

The most commonly used drugs are sodium hydroxybutyrate, modafinil, and antidepressants with an activating effect [8]. Sodium hydroxybutyrate (gamma-hydroxybutyric acid) increases the duration and presence of both delta and REM sleep. Given the fact that nighttime sleep disturbance is a leading symptom in narcolepsy, improving the quality of nighttime sleep reduces “sleep pressure” during the day and reduces the severity of drowsiness. In addition, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid is effective against other symptoms of narcolepsy: cataplexy, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations.

Because of its short half-life (30 minutes) and duration of action of two to four hours, to fully consolidate six to eight hours of sleep, sodium hydroxybutyrate must be taken twice: just before bed and in the middle of the night. The initial dose of the drug for adults is 4.5 g per day. Then, under the supervision of a doctor, the dose of the drug can be increased step by step (by 1.5 g every three to seven days) to a total of 6 to 9 g per day. The most common side effects include nausea and weight loss. It should be noted that due to the strong sedative effect of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid, the symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome may intensify.

The exact mechanism of action of modafinil is unclear, although numerous studies have demonstrated increases in monoamine levels with drug use: dopamine in the striatum and nucleus accumbens, norepinephrine in the hypothalamus and ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, and serotonin in the amygdala and frontal cortex. The starting dose of modafinil is 100 mg in the morning. Then the daily dose of the drug is increased to 200 mg with 100 mg taken in the morning and at noon. In the future, the daily dose can be increased to 400 mg. For armodafinil, the starting dose is 50 mg in the morning with a possible subsequent increase to 250 mg. Experience shows that the stimulating effect of modafinil drugs is sufficient in more than 50% of cases. A common side effect is headache, but this can be avoided by increasing the dosage more slowly and gradually. In addition, there may be an increase in anxiety and increased blood pressure. Like many other drugs, modafinil can cause an allergic reaction, in severe cases Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Currently, modafinil is not registered in the Russian Federation.

The situation with the treatment of cataplexy is somewhat better in our country. Stimulant antidepressants have very little effect on sleepiness, but are very effective against the accompanying symptoms of narcolepsy: cataplexy, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations. The drugs of choice today are selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: venlafaxine, less commonly duloxetine. Unfortunately, venlafaxine has a short duration of action, so it is preferable to use extended-release dosage forms of the drug. As a rule, the drug is effective in relatively small doses, from 37.5 to 150 mg in the morning. The prescription of fluoxetine (20–60 mg/day), given the longer period of action of the drug, is justified in the presence of depressive or anxiety symptoms accompanying narcolepsy. In addition, clomipramine or imipramine (25–200 mg/day) can be used. However, it is necessary to take into account possible side effects due to anticholinergic properties: accommodation disorder, constipation, urinary retention, dry mouth, cardiac conduction disturbances, orthostatic hypotension, decreased threshold for convulsive activity. Unlike cases of depression or anxiety, the action of antidepressants in cataplexy develops immediately. It is important to note that abrupt withdrawal of drugs can lead to a significant increase in cataplexy, up to “cataplexy status”.

Prescribing medications for hypersomnia requires an individual approach. In each specific case, before prescribing a drug, it is necessary to weigh the possible benefits of its use and the risk of side effects and complications. In any case, therapy begins with minimal doses with a gradual increase until effective. Patients can take the drugs daily or periodically in situations that are particularly significant to them.

In addition to drug therapy, individual adaptation of the patient is very important, including professional and social rehabilitation aimed at maintaining the patient’s social status, employment in an accessible profession, psychological correction, and other measures of social assistance. It is necessary to conduct psychotherapy with the patient and his family members in order to explain the essence of the disease, develop the right attitude and adaptive behavior in conditions of illness, and increase the patient’s self-esteem. As a behavioral therapy, the technique of planned daytime falling asleep is used (planning sleep one to three times a day). In addition, it is necessary to adhere to the principles of sleep hygiene and adherence to a routine.

In conclusion, it must be emphasized that the problem of hypersomnia is an important clinical aspect of sleep medicine, and doctors are still not sufficiently informed about this problem. We hope that the information provided in this article will help improve the diagnosis and treatment of these fairly common conditions.

Diagnosis of hypersomnia

Making a correct diagnosis for hypersomnia requires a complex of diagnostic procedures, since it is very important to clarify the form of hypersomnia and its etiology; this is the only way to prescribe appropriate therapy. Therefore, in addition to a standard neurological examination and history taking, a number of additional studies may be required, and in some cases it is advisable to involve additional specialists (traumatologist, psychiatrist, ophthalmologist, cardiologist, gastroenterologist).

In the process of collecting anamnesis, attention is focused on the presence of genetic diseases, recent head injuries, concomitant pathologies, as well as the general rhythm of life of the patient.

Additional methods for studying hypersomnia include specific tests (sleep latency test, Stanford School of Sleepiness).

An important diagnostic role in identifying pathologically increased sleepiness is to perform a polysomnographic study. Polysomnography allows you to clarify the form and features of the clinical course of hypersomnia.

It is also important to differentiate hyposomnia, which has developed against the background of other pathologies, from increased drowsiness with an organic etiology (as a result of asthenia, chronic fatigue syndrome, depression), since this is the only way to prescribe optimal therapy. Such differentiation often involves echo-EG, CT of the brain, ophthalmoscopy, etc.

Mental disorders

It should be kept in mind that the major mental disorders are now known to have a biological basis and thus represent a subset of medical conditions.

Depression can lead to changes in REM sleep. Almost 40% of people suffering from depression have insomnia. PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) can cause vivid and terrifying nightmares. Anxiety disorders predispose to insomnia. The most common of these are generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other anxiety disorders. Thought disorders and misperceptions of sleep status can also potentially cause insomnia

Psychotropic medications such as antidepressants can disrupt normal REM sleep patterns. Rebound syndrome during withdrawal of benzodiazepines or other hypnotics is common.

Treatment of hypersomnia

Treatment of hypersomnia has a direct relationship with the accuracy of diagnostic results and elimination of the underlying disease. In some cases, the disease that causes hypersomnia cannot be completely cured, then therapeutic tactics are aimed at minimizing symptoms that negatively affect the patient’s quality of life.

An important point in the fight against this pathological condition will be the normalization of sleep patterns. Patients need to abandon the daily work schedule and go to bed at the same time. You also need to include 1-2 times of daytime sleep in your daily schedule, while the duration of night sleep should not be more than 9 hours. To achieve positive results in the treatment of hypersomnia, it is necessary to stop drinking alcohol, exclude heavy foods from the diet (too fatty, smoked) and try to avoid eating immediately before going to bed.

Drug therapy for a hypersomnic state involves the use of the following stimulant drugs:

- propranolol;

- modafinil;

- dextroamphitamine;

- mazindol.

For cataplexy phenomena, patients are prescribed antidepressants:

- viloxazine;

- clomipramine;

- protriptyline;

- fluoxetine, etc.

After all therapeutic measures have been implemented, the patient must be provided with dynamic monitoring, since hypersomnia is prone to relapses.

Medical conditions

Heart diseases that can lead to sleep disturbances include myocardial ischemia and congestive heart failure. Neurological conditions include stroke, degenerative diseases, dementia, peripheral nerve injury, myoclonic seizures, restless legs syndrome and central sleep apnea. Endocrine diseases affecting sleep are associated with hyperthyroidism, menopause, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and hypogonadism in older men.

Pulmonary diseases include diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, central alveolar hypoventilation and obstructive sleep apnea (associated with snoring). Gastrointestinal conditions include gastroesophageal reflux. Hematological diseases include: paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, hemolytic anemia associated with brownish-red morning urine.

Substances that can lead to insomnia include stimulants, opiates, caffeine and alcohol, or quitting any of these can cause insomnia. Medications that may be implicated in insomnia include: decongestants, corticosteroids, and bronchodilators.

Other conditions that can affect sleep include fever, pain and infection.

Prognosis of hypersomnia

The prognosis, as well as the treatment of a hypersomnic state, depends on the cause of its development. For example, with post-traumatic hyposomnia in most cases it is favorable; very often increased drowsiness disappears upon completion of treatment and rehabilitation of the patient. With narcoleptic hypersomnia, as well as organic brain lesions, the prognosis is less favorable. Hypersomnia itself is not a fatal pathology, but it significantly increases the risk of injury, since the patient can fall asleep at any moment.

Description

Hypersomnia is classified as a sleep disorder. It is characterized by an increase in its duration at night and increased sleepiness during the day. With this pathology, the duration of sleep increases significantly. Despite this, the patient constantly does not get enough sleep and does not feel cheerful after waking up. Its main signs are considered to be:

- the need for long night sleep of more than ten hours;

- paroxysmal or constant drowsiness during the day;

- after a nap there is no noticeable improvement in the condition;

- difficult and prolonged period of waking up;

- the presence of a feeling of “drunk intoxication” - when waking up, dizziness appears, the patient finds it difficult to get up, he feels unwell.

In case of hypersomnia, the need for long-term sleep is assessed using an individual approach. This is compared to the duration before the problems with excessive sleepiness occurred. The diagnosis of hypersomnia is made if such symptoms last for at least three months.

Diagnostics

Differential diagnosis must be made with the following conditions:

- Alcoholism

- Anxiety disorders

- Bipolar affective disorder

- Sleep disorder associated with breathing

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Depression

- Emphysema

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Opioid abuse

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

Laboratory tests for sleep disorders may include the following studies:

- Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels

- Arterial blood gases

- Thyroid hormone levels

- Drug testing

For diagnostic purposes, oximetry may be performed during sleep to determine blood oxygen levels in the presence of sleep apnea and breathing disorders.

Medical imaging methods (MRI, MSCT) cannot directly identify the cause of insomnia, but they help determine the presence of morphological changes in the brain or other organs.

Subjective sleep ratings are obtained using a sleep log.

Objective measures of sleep can be obtained using electroencephalography (EEG) or polysomnographic studies. Techniques such as multichannel EEG, electrooculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG), oximetry, abdominal and thoracic motion studies, and electrocardiography (ECG) may also be used. Patients with chronic illnesses such as fibromyalgia or anxiety disorders often have a characteristic alpha rhythm of brain wave activity that occurs during the deep stages of sleep. When diagnosing sleep disorders, consultation with psychiatrists is often required. The group for optimal assessment of the cause of sleep disorders should optimally include a psychiatrist, neurologist, pulmonologist, specialist somnologist and nutritionist.