08.12.2016

Pinchuk Elena Anatolyevna

Deputy chief physician for medical work, kmn, neurologist, doctor of physical and rehabilitation medicine

Maltseva Marina Arnoldovna

Head of the consultation department - neurologist, specialist in the field of extrapyramidal pathologies, doctor of the highest category

Kritskaya Olga Pavlovna

Neurologist, highest category

One third of the total mass of the human cerebral hemispheres is in the frontal lobes. If blood circulation is disrupted in this particular part of the brain, then, first of all, all cognitive (cognitive) processes suffer.

The main causes of impaired blood flow in the vessels of the frontal lobes of the brain are exacerbations of hypertension, atherosclerosis, some congenital pathological diseases of blood vessels, poor blood clotting, and a tendency to thrombus formation. All this leads to a stroke. Depending on its mechanism of action, a stroke can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. Further, in turn, the stroke leads to the development of frontal syndrome. It is important to note that stroke is not the only cause of this disease. However, symptoms may

Symptoms of frontal stroke

Frontal stroke most often manifests itself in the form of general cerebral symptoms:

- A person experiences acute pain in the front of the head, nausea and vomiting.

- Dizziness leads to loss of consciousness.

- A high body temperature may rise.

Specific symptoms of frontal stroke:

- Rudimentary reflexes appear: sucking, grasping, searching (in the case of extensive damage to the frontal lobes);

- A person loses the ability to control his own actions;

- The sense of self-awareness is lost;

- There are motor and speech disorders;

- The ability for abstract thinking and planning is lost;

- The functions of memory, attention and will of a person are impaired;

- The victim is unable to focus on anything, cannot solve complex problems, make logical connections, form concepts, etc.

Symptoms may also vary depending on the location of the damage. In case of a stroke on the left side of the frontal part of the brain, a person's verbal behavior is impaired. He is unable to quickly remember and name familiar objects, and cannot speak at a fast pace. If the damage occurs on the right side of the frontal part of the brain, then nonverbal fluency is impaired.

It is believed that lesions in the prefrontal region of the brain lead to disruption of a person’s executive functions. A person who has suffered a stroke of the frontal lobes may retain some motor functions, intelligence and perception, but at the same time the behavior and the very personality of the victim are distorted. Often such consequences are unnoticeable while the patient is still being treated in a medical facility. But over time, these deviations will become more and more apparent. The doctor’s task is to collect a complete history of the onset and course of the disease in order to subsequently correctly prescribe the necessary therapy.

Frontotemporal degenerations in the practice of a neurologist

The article discusses the epidemiology, main clinical manifestations, principles of diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment of frontotemporal degeneration. There is a need to conduct clinical studies of the effectiveness of Cerebrolysin in this group of diseases.

Clinical symptoms of frontotemporal degeneration

Epidemiology

Frontotemporal degenerations (FTD) are a heterogeneous group of progressive neurodegenerative diseases predominantly affecting the frontal and/or anterior temporal lobes of the brain [1–7]. FTD is the fourth leading cause of significant neurocognitive impairment after Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and cerebrovascular disease. Among presenile patients (up to 65 years), FTD is second only to Alzheimer's disease in prevalence. Overall, FTD occurs with an incidence of 3 to 26% [8]. The incidence averages 1.6 cases per 100,000 population per year and increases significantly between the fifth and seventh decades of life [9].

Clinical forms

The following main clinical variants of FTD are distinguished: behavioral form and primary progressive aphasia syndrome (PPA). PPA syndrome is in turn divided into agrammatic subtype and semantic dementia. Some researchers also include corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis–frontal-type dementia complex as FTD spectrum diseases [1–7, 10, 11]. It should be noted that the division into clinical forms is relevant only in the initial stages of the disease. As the pathological process progresses, the differences between them are erased, so a nosological diagnosis can be established only with the help of molecular genetic or pathomorphological studies [7].

FTD usually debuts at the age of 55–65 years, but cases of the disease have been described at 25 and 89 years of age [7]. Life expectancy in patients from the moment of diagnosis depends on the clinical form of FTD: the longest (over five years) with the agrammatic form of PPA and the shortest (about a year) with a combination of FTD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [12].

A positive family history is traced in 30–40% of cases of FTD, while forms with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance account for about 15% [9, 13]. Familial cases of FTD are typically associated with mutations in three genes: tau (or microtubule-associated protein), progranulin, and C9orf72. These genes account for the vast majority (more than 80%) of cases of familial FTD [14].

The pathomorphological picture of FTD is represented by atrophic changes in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. It is also possible that the parietal cortex, substantia nigra, striatum, other subcortical structures and anterior horns of the spinal cord are involved in the pathological process, which is reflected in the clinical picture of the disease. Histological examination reveals inclusions of DNA-associated protein (TDP-43) in 50% of cases of FTD, tau-positive inclusions in 40% of cases, and inclusions of oncogenic proteins in a small percentage of cases [15].

The behavioral form of FTD accounts for more than half of FTD cases and is characterized by a combination of cognitive, behavioral and emotional-affective disorders (Table). Although emotional and behavioral disturbances are present in many neurodegenerative diseases, in the behavioral form of FTD they are the earliest, most noticeable, and disabling manifestations. The range of non-cognitive symptoms in the behavioral form of FTD depends on the location of the pathological process and the stage of the disease [1–7].

A decrease in social intelligence is one of the earliest signs of FTD and reflects the involvement of the cingulate gyrus and the anterior cortex of the temporal lobe, predominantly of the right hemisphere, in the pathological process. There is emotional coldness, decreased empathy for loved ones and friends, and indifference to the feelings of other people. Patients may remain indifferent to the loss of a loved one or react inappropriately to funerals or other important family events. This often leads to intra-family conflicts [16].

Apathy is the most common symptom of FTD, the development of which is associated with atrophy of the anterior cingulate cortex. Patients have reduced motivation for any activity, weakened interest in work, hobbies, communication and hygiene. They are often unable to begin or continue any daily activities without reminders, prompts, or constant guidance. At the same time, patients do not realize their defect, and relatives often perceive apathy as laziness or depression [17].

Disinhibition is a common symptom of FTD, which develops when the orbitofrontal cortex and the medial parts of the temporal lobe cortex, usually the right hemisphere, are predominantly involved in the degenerative process. Patients commit impulsive acts (for example, careless spending), become tactless, and violate socially accepted norms of behavior. May engage in illegal activities, such as careless driving, theft, urination or exposure in public, and violence. Typical manifestations include foolishness, flat humor, inappropriate remarks and comments when communicating with unfamiliar people, and sexual incontinence. In most cases, patients are uncritical of their actions [17].

An eating disorder is characterized by a change in eating habits, an addiction to sweet and carbohydrate-rich foods appears, and bulimia may develop with a loss of the feeling of satiety. Excessive smoking and alcohol abuse are also typical. In advanced stages of FTD, as a rule, hyperoralism is observed, that is, a constant desire to chew something, to taste all visible objects, including inedible ones. Changes in food habits correlate with degeneration of the right orbitofrontal cortex, insular cortex and ventral hypothalamus [18].

Stereotypic behavior is a fairly common and early clinical symptom of FTD; it is characterized by an excessive need to perform the same actions. Simple stereotypical behaviors may include tapping, picking, rocking, humming, and other motor compulsions. More complex compulsive (ritual) behaviors include hoarding, mindless walking along the same routes, excessive trips to the bathroom, and “tidying up.” The development of stereotypic behavior is associated with atrophy of the supplementary motor cortex in the right hemisphere [17].

Emotional and affective disorders in the form of anxiety and depression are found in a quarter of patients with the behavioral form of FTD, often at the onset of the disease. The origin of anxiety and depression is associated with dysfunction of the anterior parts of the right temporal lobe [19]. In some patients, more often in carriers of the C9orf72 gene mutation, psychotic disorders (delusional and hallucinatory disorders) have been described already in the prodromal stages of the disease [20].

Cognitive impairments in the behavioral form of FTD are represented by impairments in frontal executive functions (goal setting, planning and control). However, in the early stages of the disease, many patients perform well on formal neuropsychological tests. This is due to the fact that tests for assessing executive functions (frontal test battery, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, etc.) mainly assess the functions of the dorsolateral parts of the prefrontal cortex, while changes in personality and behavior are associated with dysfunction of the medial and orbitofrontal parts [21 ]. For this reason, early diagnosis of behavioral FTD relies heavily on a detailed history obtained with the help of a close relative or other person who knows the patient well. Tests to assess social intelligence, including tests of emotion recognition and empathy, may be sensitive for detecting FTD, but they are rarely performed in clinical practice and are not included in current diagnostic criteria [1, 22].

Speech impairments in the form of progressive aphasia are very characteristic of FTD. With predominant interest in the left frontal lobe, a decrease in spontaneous speech activity is observed. Patients are extremely laconic, answer questions in monosyllables, and do not start a conversation on their own. When the left temporal lobe is involved in the degenerative process, the understanding of the meaning of nouns in spoken speech is disrupted (alienation of the meaning of words). Patients begin to ask the interlocutor what this or that word means. At advanced stages of the disease, speech disorders often progress until the development of mutism [2, 4, 5, 23].

In the initial stages of the disease, cognitive functions such as memory, praxis, gnosis and counting are relatively preserved. But with the progression of the pathological process, the development of visuospatial disorders and memory impairments is possible [2, 24].

In some cases, FTD begins with speech disorders with relative preservation of other cognitive functions and normal patient behavior. The diagnostic criterion for primary progressive aphasia syndrome is considered to be gradually increasing dysphasic disorders for no apparent reason in the absence or with minimal severity of memory impairment and other cognitive functions for two or more years [5, 10, 11].

With the agrammatic variant of PPA, the clinical picture resembles transcortical motor aphasia (dynamic aphasia according to A.R. Luria). Spontaneous speech activity decreases, patients speak in simple sentences or phrases with a minimum number of words. The grammatical structure is disrupted (wrong endings of words, incorrect use of prepositions, case constructions, etc.) both in spontaneous and written speech. At the same time, oral apraxia may occur. At the same time, understanding of the addressed speech is not impaired. As the disease progresses, repeated speech suffers, echolalia and speech stereotypies may occur. In the most severe cases, mutism develops.

The semantic form of PPA is characterized by such clinical signs as impaired naming of objects (anomia) and difficulties in understanding words in spoken or written speech. The patient’s own speech retains the correct grammatical structure, but some nouns may be replaced by others that are similar in meaning (verbal paraphasias), or by pronouns (“this”, “she”). At advanced stages of the disease, the patient is not only unable to name this or that object, but also cannot explain its purpose; he only describes what he sees. When the right hemisphere is involved, prosopagnosia (impaired recognition of faces) is sometimes observed [5, 10, 11].

As a rule, several years after the onset of PPA syndrome, other cognitive and behavioral disorders join speech disorders. Thus, at a certain stage of the disease, the differences between the clinical variants of FTD disappear [9, 25–27].

In the neurological status, most patients with FTD are asymptomatic, but there may be positive symptoms of oral automatism, the phenomenon of countercontinence, and the grasping reflex. In a small proportion of patients with various forms of FTD, along with cognitive and emotional-behavioral disorders, signs of corticobasal syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, and symptoms of upper and lower motor neuron damage may develop [26, 28].

Diagnostics

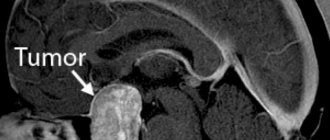

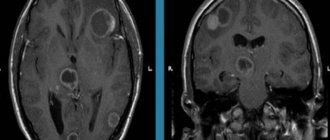

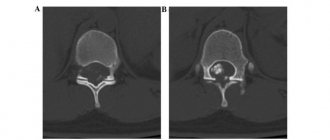

Lifetime diagnosis of FTD includes a comprehensive analysis of anamnestic, clinical and neuroimaging data. Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with behavioral form of FTD usually reveals atrophy of the frontal and/or anterior temporal lobes of the brain, often asymmetrical, as well as in some cases atrophy of the parietal lobes and subcortical nuclei [29]. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain of patients with agrammatic form of PPA reveals atrophy of the dominant hemisphere, with predominant involvement of the frontal lobe. In the semantic form of PPA, asymmetric atrophy of the temporal lobes develops, most often on the left [11].

Single-photon emission computed tomography and positron emission tomography, which are more sensitive than magnetic resonance imaging, can detect frontal and/or temporal hypoperfusion and hypometabolism. However, due to high cost and low availability, these methods are rarely used in clinical practice.

Specific biomarkers of the pathological process in FTD have not been established.

According to the criteria proposed by an international group of experts, a diagnosis of a possible behavioral form of FTD is established if there are at least three signs of the following: disinhibition, apathy, emotional indifference, stereotypic behavior, changes in eating behavior, impaired executive functions. For a probable diagnosis, in addition to the above, there must be significant impairment in daily activities and characteristic changes on neuroimaging. A definite diagnosis is made by identifying typical pathological changes or known genetic mutations [1].

Differential diagnosis

“Frontal” symptoms and non-cognitive neuropsychiatric disorders necessitate differential diagnosis of FTD with other neurological and psychiatric diseases.

The greatest difficulties arise in the differential diagnosis of FTD with atypical forms of Alzheimer's disease. The full-blown clinical picture of Alzheimer's disease may be preceded by the logopenic form of PPA syndrome, which is manifested by difficulties in selecting words in spontaneous speech and naming (logopenia), and impaired repetition of phrases and sentences. However, unlike the agrammatic form of PPA, the logopenic form preserves the grammatical structure of speech and, unlike the semantic form of PPA, speech understanding is not affected [30]. It is even more problematic to distinguish FTD from the “frontal” form of Alzheimer's disease, which, like FTD, is characterized by impaired executive functions, behavioral disorders and presenile age of onset of the disease. In this case, the study of biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease (assessment of the levels of beta-amyloid, total and phosphorylated tau protein in the cerebrospinal fluid, positron emission tomography with Pittsburgh substance) can help in the differential diagnosis [31, 32].

Currently, in the absence of reliable biomarkers for FTD, the main clinical difficulty is in the differential diagnosis of FTD with psychiatric diseases. In a study of 252 patients with neurodegenerative diseases observed in a specialized clinic, more than 50% of patients with FTD were misdiagnosed with a psychiatric disease [33]. The presence of stereotypic behavior in FTD leads to the misdiagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder. FTD symptoms such as disinhibition and impulsivity may be incorrectly attributed to bipolar disorder. However, unlike bipolar disorder, disinhibition in the behavioral form of FTD is progressive and does not always respond to pharmacotherapy. Apathy, loss of initiative, emotional indifference, and decreased empathy in the early stages of FTD can be mistaken for depression, although patients with FTD often do not have other symptoms typical of depression and do not usually complain of feelings of sadness. The presence of psychotic symptoms at the onset of FTD in carriers of the C9orf72 gene mutation also often does not allow distinguishing FTD from primary psychiatric causes [33, 34].

Treatment

Awareness of relatives and caregivers is of great importance in the management of patients with FTD. It is important to provide them with complete and detailed information about the diagnosis, the nature of the disease, existing and expected future symptoms. It should be explained how to behave with the patient in various situations, how to relate to certain manifestations of the disease. For example, it is recommended to maintain a warm emotional climate in the family, to encourage the patient’s friendly attitude towards others, and his reasonable activity in the social and everyday spheres. Mental stimulation and cognitive training will be helpful [35].

The heterogeneity of the morphological and molecular substrate in FTD significantly complicates the search for effective therapy. FTD, like other neurodegenerative diseases, is characterized by multiple neurotransmitter deficiencies. Some studies in FTD have shown insufficiency of the serotonergic system (reduction in the number of serotonin receptors and death of raphe nucleus neurons) [36]. According to these data, the use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors is justified. Their beneficial effects on the most common non-cognitive neuropsychiatric symptoms of FTD, including stereotypies, disinhibition, eating disorders and sexual incontinence, have been reported in separate placebo-controlled studies. At the same time, serotonergic drugs do not affect the cognitive functions and functional status of patients [37–39].

There are no controlled studies of the effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs for the management of behavioral symptoms in FTD. However, these agents are not recommended due to the high risk of extrapyramidal side effects, to which patients with FTD are particularly vulnerable [40].

In contrast to Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia, in FTD the deficit of the acetylcholinergic system is slightly expressed [36]. Although acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are ineffective in FTD, they are sometimes recommended as a trial therapy due to the significant clinical variability of Alzheimer's disease and the inability to accurately differentiate it from FTD [41]. Memantine also did not show a positive effect on cognitive and behavioral functions in two placebo-controlled studies conducted in a relatively small group of patients with different forms of FTD [42].

Drugs with neuroprotective effects are of great interest. Cerebrolysin is a natural preparation obtained from the brain of pigs, containing biologically active polypeptides and amino acids. The experiment showed that the active substances of Cerebrolysin are similar in their effect on brain neurons to nerve growth factor. When using Cerebrolysin, neuronal plasticity and the number of dendrites increase, new synapses are formed, intraneuronal metabolism and neurogenesis are activated, new vessels are formed and blood supply to the brain improves [43]. In the USA, Cerebrolysin is approved as an innovative drug, and its study in some orphan diseases, including FTD, is allowed [44].

Numerous clinical studies have convincingly demonstrated the effectiveness of Cerebrolysin in Alzheimer's disease, traumatic brain injury, vascular cognitive disorders, and in the acute stage of stroke [45].

A meta-analysis of six studies assessing the effectiveness of Cerebrolysin in Alzheimer's disease (the drug was prescribed in a dose of 10 to 60 ml for five days a week for four weeks) showed a significant positive effect of the drug on cognitive functions and the safety of its use, including including in elderly patients [46]. It was found that the use of Cerebrolysin in patients with Alzheimer's disease increased the content of cerebral neurotrophic factor, which can slow down the progression of the disease and the rate of cognitive decline [47].

A Cochrane review (2013), based on the results of six studies (n = 597), confirmed the positive effect of Cerebrolysin in doses of 15–30 ml on cognitive function in patients with vascular dementia [48].

Administration of Cerebrolysin in the acute period of stroke had a beneficial effect on the speed and completeness of recovery of motor disorders and reduced the severity of cognitive disorders. A meta-analysis of nine double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies in which Cerebrolysin was administered daily at a dose of 30–50 ml/day for 10–21 days from the first three days of ischemic stroke demonstrated a significant reduction in the severity of neurological disorders in the drug group compared with the placebo group [49 ].

Conclusion

A thorough assessment of behavioral disturbances and the emotional sphere in patients with FTD is of great importance for a differentiated approach to treatment and a more accurate determination of the prognosis of the disease. It seems appropriate to conduct clinical studies of the effectiveness of Cerebrolysin in FTD.

Consequences of frontal stroke

The consequences of a frontal stroke can be expressed in the form of frontal syndrome. There are two types of this disease: abulic and disinhibited.

The abulic type leads to the loss of a person’s ability to think creatively, initiative, and curiosity. Often there is a disturbance in the emotional background, manifested in the form of apathy and indifference.

The disinhibited type of frontal syndrome is directly opposite to the abulic type - impulsive behavior occurs, a person loses common sense in their actions, and is unable to foresee the consequences of their actions. Memory and thinking are completely preserved. Thus, a person is able to characterize his actions in possible situations, but in practice he will act completely inadequately and unpredictably.

Clinical Brain Institute Rating: 4/5 — 10 votes

Share article on social networks

a) Somatosensory afferent synthesis disorder syndrome (SSAS)

This syndrome occurs when the upper and lower parietal regions are affected ; the formation of its constituent symptoms is based on a violation of the factor of synthesis of cutaneous-kinesthetic (afferent) signals from extra- and proprioceptors.

1. Inferior parietal syndrome of SSAS disorder occurs with damage to the postcentral middle-inferior secondary areas of the cortex, which border on the areas of representation of the hand and speech apparatus.

Symptoms:

- astereognosis (impaired identification of objects by touch),

- “tactile agnosia of object texture” (a more severe form of asteregnosis),

- “finger agnosia” (inability to recognize one’s own fingers with eyes closed),

- “tactile alexia” (inability to recognize numbers and letters “written” on the skin).

- Possible speech defects in the form of afferent motor aphasia, manifested in difficulties in the articulation of individual speech sounds and words in general, in the confusion of similar articles.

- Other complex movement disorders of voluntary movements and actions such as kinesthetic apraxia and oral apraxia are possible.

2. Upper parietal syndrome of CVS disorder is manifested by disorders of body gnosis, i.e. violations of the “body scheme” (“somatoagnosia”).

More often, the patient has poor orientation in the left half of the body (“hemisomatoagnosia”), which is usually observed when the parietal region of the right hemisphere is affected.

Sometimes the patient experiences false somatic images (somatic deceptions, “somatoparagnosia”) - sensations of a “foreign” hand, several limbs, reduction, enlargement of body parts.

With right-sided lesions, one’s own defects are often not perceived—“anosognosia.”

In addition to gnostic defects, SSAS syndromes with damage to the parietal region include modality-specific impairments of memory and attention .

Violations of tactile memory are detected during memorization and subsequent recognition of a tactile pattern.

Symptoms of tactile inattention are manifested by ignoring one (usually on the left) of two simultaneous touches.

Modality-specific defects (gnostic, mnestic) constitute the primary symptoms of damage to the parietal postcentral areas of the cortex; and motor (speech, manual) disorders can be considered as secondary manifestations of these defects in the motor sphere.

Programs:

Assessment of rehabilitation potential

Movement restoration

Rehabilitation after stroke

Restoration of cognitive functions

Early (resuscitation) rehabilitation

Epilepsy of the occipital and parietal lobe

Any age of onset. Most patients with epilepsy of the occipital and parietal lobe were over 16 years of age at the onset of the disease. The disease rarely begins before age 6 years. This feature distinguishes TE from GE.

Seizures in TE are simple partial sensory attacks in the form of tingling, numbness, and an electrifying sensation. Paresthesias may be localized or distributed in a Jacksonian pattern. There may be a desire to move a part of the body or a sensation as if a part of the body has already moved. Most often, those areas that have the largest cortical area are affected - for example, the arm, shoulder and face. You may experience a numb sensation with a tingling tongue, a hard tongue, or a cold tongue. Sensory disturbances in the facial area can be bilateral. Sometimes, especially when the lower and lateral parietal lobes are affected, feelings of nausea, choking or suffocation appear. The sensation of pain occurs rarely and is more often perceived as a superficial burning sensation or an occasional, vague, very painful sensation.

Visual manifestations of damage to the parietal lobe can be colorful and take on an animal-like appearance. Metamorphopsia may occur with distortion, reduction or elongation of the image, which is more often observed with discharges in the non-dominant hemisphere. Along with these “positive” phenomena or productive symptoms, so-called negative phenomena are also formed, manifested, in addition to numbness, by a feeling of the absence of any part of the body, loss of the ability to recognize part or half of the body - asomatagnosia (more often with right-sided seizures). Severe dizziness may indicate involvement of the suprasylvian parietal lobe. Seizures of the left posterior lobe are accompanied by receptive and conductive speech disorders (Wernicke's center).

A fairly rare sensory disorder involving the paracentral lobule affects both lower extremities. Seizures of the paracentral lobule tend to be secondary to generalization.

In case of ZE, seizures are usually manifested by visual symptoms: simple - volatile visual porropsia (scotoma, hemianopsia, amaurosis, or sparks, flashes). More often they are in the visual field opposite to the place of discharge in the visual cortex. Illusions of perception with distortion of objects: one-sided diplopia, changes in size, distance, location of objects in a certain part of space, distortion of objects, sudden change in shape. Visual hallucinatory seizures can be complex and take the form of colorful scenes. Along with this, the scene may be distorted or reduced, and sometimes a person may see his own image (discharges in the temporo-occipital cortex).

Seizures may present without visual symptoms - contraversion of the eyes or head and eyes, twitching of the eyelids, forced closing of the eyes, a sensation of trembling of the eyes or the whole body, isolated dizziness or dizziness and unsteady walking, together with headache and migraine.

Neurology - focal neurological symptoms.