Myoclonic epilepsy is a type of epileptic seizure. Characterized by a milder flow. The disease first appears in infants or young children. The onset of myoclonic epilepsy in adulthood is atypical. This form of the disease is characterized by flaccid muscle twitching. Symptoms resemble tics or hyperkinesis. In some cases, a severe course is possible. In the international classification of diseases ICD-10, myoclonic epilepsy is coded G40.3.

You can undergo diagnosis and treatment of the disease in Moscow at the Yusupov Hospital. The examination is carried out by experienced neurologists and epileptologists using modern medical equipment. The therapy meets European standards of quality and safety.

Causes of myoclonic epilepsy

At present, the exact causes of the development of myoclonic epilepsy have not been established. However, doctors identify several predisposing factors. Among them:

- Hereditary predisposition. Certain types of myoclonic epilepsy are hereditary. For example, Unferricht-Lundborg disease, Dravet syndrome. If one of your relatives has been diagnosed with epilepsy, then subsequent generations are at risk. The probability of the disease occurring is 20-30%.

- Intrauterine infection. Some infectious agents are able to penetrate the placental barrier. As a result, the risk of developing not only myoclonic epilepsy, but also mental disorders and developmental defects increases. Myoclonic epilepsy develops at the end of the 2nd-3rd trimester.

- Diseases during pregnancy are not infectious. This group of diseases includes diabetes mellitus, thyroid pathology, kidney, liver, and heart failure.

- Uncontrolled use of drugs during pregnancy. Some drugs have pronounced teratogenic properties. Therefore, their intake negatively affects the development of the fetus. Doctors advise avoiding taking medications during pregnancy. If necessary, all prescriptions must be carried out by a doctor.

- Spontaneous mutations. The reasons for such changes have not yet been studied. Provoking factors are identified, the presence of which contributes to mutation processes. These include stress, sudden changes in temperature, and excessive physical activity.

General provisions

Epidemiology

According to the few epidemiological data available, SDMED accounts for less than 1% of all epilepsies (St. Paul's Center, 1997), 1.3% and 1.72% of epilepsies that begin in the first year of life (Dalla Bernardina et al., 1983). , and 0.39% of epilepsies beginning in the first 6 years of life (Ohtsuka et al., 1993).

Floor

Gender distribution: 52 boys and 27 girls.

Genetics

The genetics of SDMED are unknown. There are few patients, and cases of familial SDMED have not been described. A family history of epilepsy or febrile seizures (AF) was present in 39% of 80 patients. In 70 patients, the incidence of AF in the family was 17%, and the incidence of epilepsy was 24%. It is difficult to assess the type of epilepsy found in relatives. In 10 cases it was probably idiopathic epilepsy. In the case reported by Arzimanoglou et al (1996), the proband was the 2nd of 2 brothers, and the eldest suffered from typical epilepsy with myoclonic-astatic seizures (EMAS, Douz syndrome).

Anamnesis of life

Most patients had no history of pathology before the onset of MP. Only two (1.9%) had comorbidities: Douz syndrome (Drave et al., 1992) and hyperinsulin diabetes (Colamaria et al., 1987).

However, cases of AF are not rare: 19 out of 64 patients (30%). AFs were always simple, but rare (1-2) and were observed before the onset of myoclonus and before the start of treatment (15 cases).

Symptoms of myoclonic epilepsy

The clinical picture of myoclonic epilepsy depends on the type of disease. Among the main pathological symptoms are:

- Cramps. The disease is characterized by myoclonic seizures. They are not accompanied by severe pain. Cramps most often affect the limbs, less often the face and torso. On average, the duration of a seizure is 10-20 minutes. Consciousness is preserved.

- Loss of consciousness. Occurs extremely rarely. Characteristic of the youthful form.

- Tonic-clonic seizures. This form of seizure is accompanied by loss of consciousness and painful muscle contraction.

- Oligophrenia. Mental retardation occurs in various forms. Most often this is a disorder of creative thinking and intelligence.

- Mental disorders. Expressed by hallucinations, neuroses and borderline states.

Determining clinical symptoms is necessary to select the correct therapy. Doctors at the Yusupov Hospital develop an individual treatment plan for each patient.

Course and treatment

Children with SDMED do not experience seizures of any other type, even if they remain untreated (up to 8.5 years in one of our patients), this is especially true for petit epileptic or tonic seizures. Clinical examination results are normal. Interictal myoclonus was described only by Giovanardi-Rossi et al. (1997) in 6 patients. Analyzing the condition of our patients, we found mild interictal myoclonus in 2 according to EEG recordings. Many patients were not examined, but when CT and MRI were performed, the results were normal (33 patients).

Outcome likely depends on early diagnosis and treatment. Myoclonus is easily amenable to monotherapy with valproate, and the child’s development is appropriate for his age. If left untreated, the patient continues to have myoclonic seizures, which can lead to impaired psychomotor development and behavioral abnormalities.

Treatment methods were more or less thoroughly tested on 74 patients. 65 patients received monotherapy, 6 received polytherapy, and 3 received no treatment. Monotherapy included valproate (VPA), phenobarbital (PB), nitrazepam (NTZ). 6 patients received therapy with primidone (PRM) and ethosuximide (ESM). As a result of treatment, seizures disappeared in 69 patients (93%).

These data confirm that VPA is the first choice drug for SDMED. However, treatment should be carried out under the control of drug concentration in plasma, because improper use may lead to relapse or cause drug-resistant epilepsy.

Diagnosis of myoclonic epilepsy

Myoclonic epilepsy requires a comprehensive diagnosis. The examination includes:

- Collection of complaints and medical history. During the initial examination, the neurologist questions the patient about existing complaints, the time of their appearance, and the severity of symptoms. In addition, the duration of the attacks and the condition after them are specified.

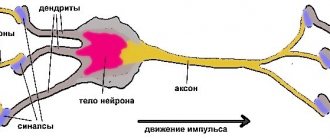

- Neurological examination. The doctor evaluates reflexes and conducts tests to assess the state of nervous activity.

- EEG. Thanks to the study, it is possible to establish the pathological activity of various brain structures. The lesion site is determined in this way.

- MRI. To enhance the effect, the examination is carried out using contrast. Myoclonic epilepsy is not characterized by the presence of structural changes in the brain. However, there are exceptions.

The Yusupov Hospital uses modern medical equipment to diagnose myoclonic epilepsy. It allows you to quickly and effectively determine the presence of the disease. Based on the data obtained, correct therapy is prescribed.

Long-term results and prognosis

The duration of observation for 63 patients was 9 months. up to 27 years, of which 45 patients were observed for about 5 years. The age of patients during the observation period ranged from under 5 to over 15 years.

In all cases, MPs were stopped. The duration of the disease is known in 52 patients: in most of them, MP lasted less than one year, in 7 - from 1 to 2 years, only in 5 - more than two years.

The occurrence of generalized epileptic seizures (GES) after cessation of MP was reported in the case of 10 patients without concomitant MP.

The results of observation of 74 patients were reported.

The attacks stopped in 28 patients over the age of 6 years. In 6 children of the same age, seizures persist: with photostimulation - in 2 (Drave et al., 1992), for an unknown reason - in 3 (Giovanardi-Rossi et al., 1997). Also, attacks persisted in 13 patients under 6 years of age. 3 patients under 6 years of age remained without treatment (Ricci et al., 1995). There is no information about 24 patients.

The EEG pattern is known for 55 patients. It quickly normalized in 23. Rare spontaneous generalized SV persisted in 13. Photosensitive changes were observed in 6. Interestingly, photosensitivity can appear after the disappearance of MP and persist for many years after the cessation of MP until adulthood. Focal abnormalities were also presented. They were recorded in 5 patients during awakening as SV in two fronto-central and parietal areas, sometimes in the fronto-parietal and fronto-temporal. They disappeared over time. On the contrary, in other patients they appeared only during sleep. They still persisted at the end of the observation period in 5 of our patients, and only during sleep.

Overall, the psychological outcome was favorable and most patients recovered. This is known for sure in 69 cases. 57 (83%) were healthy, of whom 38 were aged 5 years or older. 10 (14%) had mild retardation and attended a specialist school, but none of them were admitted to hospital. In 2 patients (3%) cognitive ability was impaired and deviations in personality formation were identified: one patient had Down syndrome and severe sensitivity, the other had MP with sensitivity to IRS and to eye closure up to 5 years of age. This psychotic disorder appeared in him at the age of 10 years and progressed.

This psychological outcome depends in part on early diagnosis, allowing appropriate treatment and reassuring the family of a good future.

These data confirm the generally good prognosis of SDMED. Seizures caused by noise or conversation were easier to control than spontaneous ones. Photosensitivity was more difficult to control and persisted for several years after the seizures stopped.

Types of myoclonic epilepsy

Myoclonic epilepsy is divided into several types. Let's look at the main ones.

Infantile myoclonic epilepsy

Diagnosed in 30-40% of cases. Characterized by symptoms such as hyperkinesis or tics. A mild degree of development of the disease can go unnoticed for many years. Intellectual development does not suffer against the background of infantile myoclonic epilepsy. The disease can appear in a child from 2 months to 3 years.

Dravet syndrome

Identified in the first year of life. Symptomatically reminiscent of infantile myoclonic epilepsy. Dravet syndrome causes severe mental disorders. They manifest themselves as oligophrenia, mental retardation. Without correct treatment, the number of attacks increases to several times a week.

Unferricht-Lundborg disease

It is considered a genetic disease. Characterized by severe neurological symptoms. Unferricht-Lundborg disease is also accompanied by mental disorders. The first attack most often occurs during puberty. The disease is diagnosed in 10-20% of cases.

MERRF epilepsy

More often diagnosed in adults. Myoclonic epilepsy of adolescence is characterized by tonic-clonic paroxysms. The disease is not accompanied by neurological disorders or mental disorders. Consciousness remains clear during the attack.

Absence seizures are a type of epileptic seizure. Considered one of the symptoms of myoclonic epilepsy.

Depending on the progression of epilepsy, the following forms of the disease are distinguished:

- Progressive. The clinical picture of epilepsy is gradually increasing. As the disease progresses, the risk of death increases. In some cases, the disease is difficult to treat.

- Stable. Symptoms remain at approximately the same level.

- Remitting. Signs of epilepsy may develop slowly and then subside over a long period of time. Over time, complete disappearance of pathological signs is possible.

TYPES OF SEIZURES IN IDIOPATHIC GENERALIZED EPILEPSY

Absence seizures are generalized seizures accompanied by a short-term loss of consciousness, cessation of gaze and the presence of specific patterns on the EEG in the form of generalized synchronous regular “peak-wave” complexes with a frequency of 3-3.5 Hz. Such absences are called typical.

First described by Poupart in 1705, and later by Tissot in 1770, who used the term "petitaccess." The term "absence" was first used by Calmeil in 1824.

The relationship between loss of consciousness and 3 Hz peak-wave complexes on the EEG was identified and described by Gibbs, Davis, and Lennox in 1935.

The prevalence of this type of attack is 1.9-8 per 100,000. Typical absence seizures are more common in girls - 2:1. Absence seizures with myoclonus are more common in boys.

In 90.6% of patients, attacks are accompanied by variable motor components (complex absences): automatisms - 63%, myoclonic component -45.5%, decreased postural tone - 22.5%, increased postural tone - 4.5%. One attack usually has two or three motor components, but three or more are rare. In the presence of motor components in the structure of the attack, absence is designated as complex, in their absence - as simple.

The classic EEG pattern of absence seizures is generalized bilaterally synchronous peak-wave complexes with a frequency of 3 Hz (Fig. 1). The peak-wave complexes are faster at the beginning of the discharge (mostly around 4 Hz), then slow down to 3.5-3 Hz in the main portion and slow down to 2.5 Hz by the end of the attack. If the peak-wave discharge is prolonged, then the frequency can be reduced to 2 Hz. If the peak-wave discharge has developed before the start of recording, then the differentiation of peak-wave and sharp-slow wave complexes may be difficult.

The maximum of peak-wave activity is almost always located above the frontal regions in the midline, and the minimum is found in the temporal and occipital leads.

The onset of peak-wave activity in the midline leads of the frontal region does not mean that the source of activity is the parts of the frontal lobe in the immediate vicinity of the interhemispheric sulcus, which is typical for all primary generalized epilepsies.

Although classic peak-wave complexes are bilaterally synchronous and symmetrical, and asynchrony usually does not exceed 20 ms, they may begin 100-200 ms earlier or be more pronounced over one hemisphere. However, such dominance may change its side over the course of one or more recordings. Rarely are classical peak-wave discharges recorded over one hemisphere.

At least 40% of patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsies have focal epileptic discharges on interictal EEG.

Clinical manifestations of absence seizure are usually pronounced when the duration of the discharge exceeds 5 seconds. Shorter outbreaks usually occur without obvious symptoms.

Absences are not obligatory and the only type of seizures that are accompanied by discharges of peak-wave complexes on the EEG - the frequency of clinically obvious absences ranges from 26% to 70%; grandmal frequency - 37-86%; the frequency of myoclonus is 14-27%. In a small number of cases, tonic, atonic seizures or only febrile seizures occur.

Differential diagnosis of absence seizures is most often carried out with atypical absence seizures, complex focal seizures of frontal and temporal origin, non-epileptic “freezing”.

Atypical absence seizures occur mainly in children with severe symptomatic or cryptogenic epileptic syndromes, which are represented by a combination of atypical absence seizures, atonic, tonic, myoclonic and generalized seizures. Clinically, the onset and end of atypical absence seizures are more gradual, changes in muscle tone are more pronounced, and there may be post-attack confusion. The EEG shows irregular peak waves with a frequency of less than 2.5 Hz or other variants of epileptic activity (Fig. 2). Background bioelectrical activity is usually changed.

Freezing with loss of reactivity can also be part of the structure of complex focal seizures in temporal or frontal epilepsy. “Frontal” absence seizures (a focus in the region of the pole of the frontal lobe) may not clinically differ from typical absence seizures; differential diagnosis is based on EEG data.

Clinical differences between complex focal seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy and typical absence seizures in IGE are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Differential diagnosis of typical absence seizures and complex focal seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy.

| Sign | Complex focal seizures (temporal lobe epilepsy) | Typical absence seizures |

| Aura | Often | Never |

| Duration | usually more than 1 minute | Usually a few tens of seconds |

| Provocation by hyperventilation | Rarely | Usually |

| Photosensitivity | Rarely | Often (depending on the syndrome) |

| Loss of consciousness | Usually deep | Variable (depending on the syndrome) |

| Automatisms | Almost always; the trunk and legs are often involved ipsilaterally. Dystonic positioning of the contralateral limbs in 40% of cases. | Up to 2/3 of cases. Minimal expression. The trunk and legs are rarely involved. |

| Outpatient automatisms | Often | Only in absence seizure status |

| Clonic seizures | Rarely; unilateral at the end of the attack | Often; bilateral, usually in the mouth and/or eyelids |

| Non-convulsive status | As an exception | May occur |

| Post-seizure symptoms | Almost always confusion, often amnesia and dysphasia | Never |

Unlike typical absence seizures, which interrupt ongoing activity, nonepileptic freezing typically occurs during periods of inactivity, can be interrupted by external stimuli, and is not accompanied by motor components or discharges on the EEG.

Myoclonus is characterized by rapid involuntary muscle contractions, usually with joint movement, generalized or limited to a specific muscle group, mainly in the flexors. Epileptic myoclonus is accompanied by epileptic discharges on the EEG.

If an epileptic discharge causes muscle tone to be “switched off,” a brief movement may occur under the influence of gravity. This option is called “negative” myoclonus.

A generalized tonic-clonic seizure is a variant of an attack represented by successive phases of continuous muscle contraction (tonic phase) and intermittent contractions (clonic phase) with loss of consciousness. The attack begins with a loss of consciousness and a sharp tonic tension of all muscles lasting 30-40 seconds. In this phase, sharp cyanosis appears. Next, rhythmic muscle spasms appear with a gradual increase in the intervals between individual contractions lasting up to several minutes. After the contraction, complete relaxation and a short-term comatose state occurs, which turns into sleep.

Treatment of myoclonic epilepsy

Medications are used to treat myoclonic epilepsy. Doctors at the Yusupov Hospital use the following groups of drugs:

- antiepileptics;

- barbiturates;

- tranquilizers;

- nootropics.

An individual treatment plan is developed for each patient. It takes into account the form of myoclonic epilepsy, stage of development, age of the patient and the presence of concomitant diseases. This approach allows you to quickly and effectively select therapy. Experienced neurologists, epileptologists, and psychiatrists conduct consultations at the Yusupov Hospital. Rehabilitation is carried out by qualified massage therapists and exercise therapy instructors. In order to make an appointment, you need to call or leave a request on the official website of the hospital.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy in children. Ed. Temina P.A., Nikanorova M.Yu. // M.: Mozhaisk-Terra. – 1997. – 656 p.

- Evtushenko S.K., Omelyanenko A.A. Clinical electroencephalography in children // Donetsk. – 2005. – p. 539-546, 585-594

- Martinyuk V.Yu. Protocol for the treatment of epilepsy and epileptic syndromes. Protocol for the treatment of status epilepticus in children. – Kiev, 2005.

- Mukhin K.Yu., Petrukhin A.S. Idiopathic forms of epilepsy: systematics, diagnosis, therapy - M.: Art-Business Center, 2000 - 319 p.

- Epileptology of childhood: A guide for doctors / Ed. A.S. Petrukhina. - M.: "Medicine", 2000. - 620 p.

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) as a separate form of idiopathic generalized epilepsy with age-dependent onset was identified in 1969 by D. Janz [1], although there is evidence in an earlier work by this author, jointly with W. Christian, in which it was named “impulsive petit mal” [2]. In addition, there is the first description of the patient, which dates back to 1867 [3]. However, despite the long period of study of JME, there are still questions and unresolved problems regarding its diagnosis and treatment.

The article provides a comparative analysis of the results of our research in accordance with the works of other authors. The results of the study by V.A. were compared. Karlova and N.V. Freidkova [4] 72 patients with JME, as well as a new sample of patients over the past 5 years (20 people) with research materials from domestic and foreign authors relating to the same time period. The evolution of the problem in the aspects of clinical diagnosis, therapy, prognosis of the disease and social adaptation of patients with JME is considered.

The age of onset of this form of epilepsy in the literature is indicated with a wide range, which is associated with the unfixed point of onset of the disease. This is explained by the fact that the onset of the disease, as a rule, is myoclonus, to which patients, and often doctors, do not attach due importance. If in our previous studies an early onset was noted at 10 years of age, and a late onset at 26, now we have recorded a case of an earlier onset, namely at 9 years of age.

As for the genetic aspect of JME, in the works of F. Elmslic et al. [5] and later other authors [6-8] identified pathological genes - BRD 2

and

EFHCI

with a locus on chromosomes 6p21, 6p12-p11 (

EJM 1

) and 5q14 (

EJM2

) with a defect in one of the genes - myoclonin. In addition, the presence of widespread disorders at the microstructural level in the white matter of the brain was confirmed - in the frontal lobe and corpus callosum. The presence of these changes is associated with frontal cognitive dysfunction, which was noted by D. Janz [1], who was the first to describe this form of the disease. He also emphasized that, although most cases of JME are isolated (single cases), approximately 1/3 of patients have a family history of epilepsy. Data from P. Thomas et al. [9] indicate that in families of patients with JME, there is a segregation of patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy, and approximately 5% of first-degree relatives have epilepsy.

According to our latest observations, epilepsy in the family was observed in 1 relative of the first degree and in 5 relatives of the first degree according to previously published studies. In 2014, a study [10] was conducted on clinical and genealogical data in probands with JME and their family members. We studied 13 unrelated families in which at least 2 members suffered from epileptic seizures. Neither maternal nor any other mode of inheritance was found. A heterogeneous phenotype was found in individuals of the second and third degrees of consanguinity: in families with JME, other forms of epilepsy are found, in particular with generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTS) in individuals with late onset JME.

Here is our own observation.

An 18-year-old patient complained of seizures from the age of 11 - “the same as the mother’s” upon awakening, and a single generalized convulsive seizure (GSE) at the age of 13. For the last two years he has been taking Convulex 750 mg 2 times a day, there have been no attacks. The breakdown of clinical remission began with the occurrence of an attack “around sleep” (when falling asleep).

Born from a 23-year-old mother, labor was at term, induced. The patient's mother was previously treated with a diagnosis of JME: she dropped objects from her hands, and had morning twitches in her hands. As prescribed by a neurologist, she took Luminal for a year, and then phenytoin (diphenin) for three years, which naturally intensified the attacks. At the age of 20, she independently stopped taking prescribed antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), at the same time the attacks practically stopped: only twitchings provoked by psycho-emotional stress remained.

An examination of the patient's neurological status revealed mild Babinsky asynergia. MRI of the brain showed a large subarachnoid cyst in the left frontoparietal region, undoubtedly congenital. The previous EEG showed mild background disorganization, absence of photosensitivity and an epileptiform response to hyperventilation. At the same time, in the slow-wave sleep phase, epileptiform discharges of the acute-slow wave and spike-wave type were recorded, mainly arising in the frontal leads, local or sometimes generalizing. The latest EEG shows their significant reduction.

There are a number of features in this observation. Firstly, the mother of a patient with a clinical picture of JME at the age of 20, against the background of self-cancellation of AEDs (which, by the way, were contraindicated for her), only a rare psycho-emotional provocation of myoclonus remained. Secondly, in the daughter, the combination of morning myoclonus with isolated sleep-related generalized seizures (GSEs) provides a known basis for the diagnosis of JME. At the same time, we believe that this case can be qualified as an “erased” form of JME, since there were no characteristic shudders and falling of objects from the hands. It can be assumed that the mother had an “erased” form of JME. In principle, these observations support the existence of a problem of sleep-related myoclonus, perhaps outside of epilepsy.

As is known, JME has a characteristic clinical pattern: bilateral, often asymmetrical irregular arrhythmic jerk-like myoclonic twitching of the muscles of the shoulder girdle and the arms themselves of varying amplitude. At the same time, myoclonic twitches are largely ignored by patients, and therefore patients, as a rule, do not contact doctors with these complaints. However, they can hardly be called unconscious, since the doctor’s leading questions are followed by a description of these attacks to the patient. Rather, this phenomenon can be explained by the characteristic features of the psyche of patients (anosognosia) [1].

Another characteristic clinical manifestation of this form of epilepsy is a generalized myoclonic phenomenon - startle. Unlike physiological shudders, this manifestation of the disease in JME occurs not so much during sleep as during the period of awakening. In one of the patients we observed, shudders predominated when going to bed. This brings JME closer to awakening GTCS epilepsy, in which seizures can occur around sleep.

The combination of myoclonus in most cases with rare GTCS (60%) is confirmed. According to our latest observations, the average time for the onset of GTCS after the onset of myoclonus was about 4 years. The combination of myoclonus only with absence seizures remains a rather rare phenomenon: we previously observed only one case, over the past 5 years there have been no such cases in our observations.

The combination of myoclonus, GTCS, atypical absence and aura, which causes some diagnostic difficulties, is reflected in the following clinical observation.

Patient X.

, 29 years old, applied in July 2013. She is a psychologist by profession, but does not work.

The prenatal and postnatal anamnesis is unremarkable, heredity is not burdened, according to the mother, it was “squeezed out” during childbirth. Against the background of apparent health, but at the same time chronic lack of sleep, in April 2012, during a trip to work on a train, the first and only GTCS occurred with a preceding feeling of the unreality of what was happening (the patient could not describe it more accurately). By the time he contacted us, therapy had already been prescribed - Topamax 50 mg per day, Lamictal 100 mg 2 times a day. This caused a deterioration - the appearance of shudders, more often associated with sleep.

MRI on one of the axial basal slices in T2 mode revealed increased signal from the pole of the left temporal lobe. Sleep EEG is represented by episodes of generalized spikes and polyspike waves, single and/or extended to several seconds (in these cases, reminiscent of atypical absence seizure).

Considering that the patient had a history of surgery for bilateral polycystic ovary syndrome (the menstrual cycle is not disrupted), and the first-line drug of choice for the dominant clinical manifestation of myoclonus may be levetiracetam, it was decided to cancel Lamictal and add Keppra 500 mg 2 times a day. In September 2013, there was a second GTCS, which the patient amnesiced, but at the same time, apparently, she felt its beginning (she left the kitchen and went to bed). In addition, there is an isolated, difficult-to-identify state of derealization. The twitching decreased. The dose of Keppra was increased to 750 mg 2 times a day and Topamax 50 mg 2 times a day was added (taking into account the patient’s excess body weight). There followed an increase in the frequency of attacks up to one per week while awake, and the patient independently discontinued the AED. After which there was no GTCS, however, general tremors occurred during sleep at night. During 12-hour EEG monitoring, bilateral synchronous peak-wave and polypeak-wave discharges with a frequency of 3.5-4 and a duration of 3-5 s were recorded during periods of wakefulness and sleep.

This case initially presented diagnostic difficulties: the differential diagnosis was made between JME and phenocopy JME. Uncharacteristic, although possible, for JME was the onset of the disease with GSP, an increase in convulsive seizures during the course of the disease, and an EEG pattern largely represented by a correlate of atypical absence. Another feature that initially led to discussion of the diagnosis of JME was the appearance of myoclonus, usually associated with sleep, due to its appearance after the prescription of a combination of Topamax (prescribed due to the patient’s excess weight) with lamotrigine. Since both of these drugs, although rarely, can provoke the appearance of myoclonus, the mere fact that myoclonus occurred not after waking up, but during sleep, did not negate the diagnosis of JME. Finally, one more significant circumstance: the self-cancellation of the drugs coincided with the spontaneous remission of GSP, although the twitching persisted. Thus, this case demonstrates that myoclonus is the essence of the disease. As for GSP, it is obvious that the first of them was provoked by lack of sleep, and the subsequent appearance and increase in frequency of attacks must be regarded as the result of an ineffective or even paradoxical effect of AEDs.

Let's return to the diagnosis. The onset of the disease is from the age of 10, when short-term episodes of “freezing” and flinching were noted; the first attack that occurred on the train was apparently associated with sleep deficiency, and the generalized changes revealed by the EEG could indicate the idiopathic nature of the disease: JME refers to idiopathic epilepsy with a varying phenotype. At the same time, a patient with GSP has a difficult-to-identify aura, which also occurs in the form of an isolated manifestation; transformation of convulsive seizures from asynchronous to seizures of wakefulness are signs characteristic of symptomatic and, to a large extent, cryptogenic epilepsy. Already in the 1989 classification, a form of epilepsy was identified with syndromes that have signs of both focal and generalized. In the later proposed and still not accepted classification in the section “Epileptic syndromes and related conditions”, the above heading was removed [11, 12]. However, the new composition of the International League Against Epilepsy (IALE) Commission on the Classification and Terminology of Epilepsy, headed by I. Scheffer [13], recently proposed the introduction of a section “Unclassified epilepsies”, which includes cases not recognized as known electroclinical syndromes, or of unknown etiology. Thus, this case does not relate to specific electroclinical syndromes and can be classified as an unclassified form of epilepsy.

Since JME can initially manifest itself for a long time only as myoclonus, EEG is of particular value. EEG in JME is characterized by such features as the presence of short bursts of polyspike and spike waves of 3-6 v s (Fig. 1); discharges of generalized symmetrical spike waves 3 in s and rarely 1-2 in s; epileptic discharges characterized by high, sometimes gigantic amplitude. Frontal-lobar activity is detected more often (Fig. 2 and 3), sleep sharply activates epileptiform activity, while emphasis can also be detected in some other leads. Although clinically absence seizures were observed in isolated cases, during EEG recording, a correlate of absence seizures was recorded in 18.1% of early studies and in 15% of later studies, while an EEG correlate of myoclonus was recorded in half of the patients.

Rice. 1. EEG of patient Kh., 29 years old, with JME.

Rice. 2. EEG of patient X., 29 years old. Frontal lobar activity.

Rice. 3. Localization of the epileptic focus according to EEG leads (explanation in the text).

Focal EEG manifestations are widespread in patients with JME [14]. Thus, in the studies of E. Montalenti et al. [15], K.Yu. Mukhina et al. [16] revealed a high frequency of regional changes and asymmetry of diffuse peak-wave discharges. According to these authors, these “atypical” changes in the EEG are often the cause of an erroneous diagnosis of focal epilepsy with the phenomenon of secondary bilateral synchronization. In this regard, it is appropriate to mention that domestic authors emphasize: the classic clinical picture is fundamental in making a diagnosis, and EEG is just an auxiliary additional research method.

Unfortunately, despite the characteristic clinical picture of the disease and progress in research methods, the problem of diagnosing and prescribing correct therapy still remains open, although positive trends are observed. If previously a correct diagnosis was made and adequate therapy was prescribed only to 34.8% of patients, then according to recent studies, initial therapy was correctly selected for 50%. We note, by the way, that phenytoin is still sometimes prescribed.

The diagnostic problem is confirmed by some foreign works. Thus, a retrospective observation of 200 patients with JME who underwent outpatient examination in 2014-2015. [17], found an incorrect diagnosis in 49 cases with the onset of the disease with GTCS and registration of generalized spike-wave or polyspike-wave discharges on the EEG in 56% of cases. In cases where the disease began with myoclonic seizures, the diagnosis did not cause difficulties. Almost half of the patients were prescribed inappropriate AEDs; the rest were recommended to be monitored. Compared to the 1998 study, the rate of misdiagnosis has become lower and the time to correct diagnosis is shorter. However, diagnosis at a glance still remains a challenge among neurologists, even when typical EEG changes occur.

A substantiated diagnosis of JME, however, does not guarantee an optimal response to therapy. This fact was reflected in the work [18] on a study of 116 patients with JME, observed for at least 18 months each. 68 patients had no seizures over the past 12 months, and 48 had at least one seizure of a different type. The most common negative factors found in the latter group were: short follow-up period, medication other than valproic acid (VA), poor adherence to therapy. In particular, in this regard, the authors recommend wider use of valproate. Other researchers [19] noted that 19% of 201 patients with JME with no response to VC showed significant correlations and associations with mental disorders. This, as well as other treatment problems and causes of relapse are discussed in this article.

One of the problems in the treatment of JME, as with other forms of epilepsy, is adverse reactions.

Patient Z.

, fell ill at the age of 11-12, when twitching appeared in the morning after sleep, she dropped objects from her hands. MRI and EEG studies were carried out, after which the disorders were regarded as functional tics. At the age of 15, she suffered from salmonellosis, against the background of which a sharp headache developed, accompanied by vomiting, aggravated by verticalization. She underwent a course of treatment in the infectious diseases department, but the headache was not relieved, and a space-occupying process in the brain was suspected. In May of the same year, she was examined at the Scientific Center for Neurology, diagnosed with myoclonus and prescribed clonazepam and finlepsin. A positive effect of initial therapy was noted, but epileptiform activity remained on control EEGs. A year later, against the background of forced self-discontinuation of medications (the AEDs ended while on vacation), GTCS developed in the morning. The dosage of clonazepam was increased. Four years later, during the morning toilet in the bathroom, there was an episode of short-term loss of consciousness; there was no post-attack sleep.

At this time, the patient first contacted the authors of the article, and the treatment was changed: Depakine Enterik 300 mg 3 times a day was prescribed. The patient's condition improved significantly: no twitching was observed, and all subsequent EEGs were positive. However, adverse reactions appeared: weight gain, menstrual irregularities, hirsutism. It was decided to prescribe Keppra 750 mg 2 times a day and reduce the dosage of Depakine. Since the side effects of Depakine persisted, it was necessary to completely remove Depakine within a year, but after 3 months the EEG deterioration continued. When the Keppra dosage was increased to 2000 mg per day, the condition remained the same. During one of the attacks, the patient almost fell on the stairs; Depakine 300 mg/day was again introduced into therapy. A year later, a pronounced deterioration was recorded on the EEG; in agreement with the patient, it was decided to switch to combination therapy with Topamax 100 mg 2 times a day and Depakine Enteric 300 mg 2 times a day. The EEG began to show positive dynamics. Later, an attempt was made to remove Depakine, but the weakness in the arms increased, uncertainty appeared in the morning, eyes rolled, and negative dynamics were recorded on the EEG. It was decided to return to the dosage of Depakine 300 mg 2 times a day.

We present this case not to illustrate the side effects of VK, they are well known, but to show what difficulties can arise if it is intolerant. Perhaps we should have tried other forms of VC.

It is known that JME is more common in females in a ratio of 2:1. This reflects another side of the problem - the gender aspect. Despite the fact that valproates are effective first-line drugs for JME, in many cases they cannot be used in an effective dose in females of reproductive age due to severe side effects, as illustrated above. This problem was discussed by the European Academy of Neurology, and a recommendation was made to limit the use of valproate in this category of patients [20].

V. Puri et al. [21] tried to find the neurophysiological mechanism of the prevalence of morbidity in women using the method of transcortical magnetic stimulation in previously untreated patients. Increased activity was found in the cortical inhibitory neural network, “apparently due to a long period of cortical silence.” This phenomenon was found only in female patients, which the authors explain the increased sensitivity to this disease in the female cohort and, accordingly, the possible significance of the hormonal factor (estrogen).

In connection with the above, it is relevant to further search for an alternative drug VK for the treatment of JME in women.

Levetiracetam, which is highly effective against both myoclonus [22, 23] and in blocking interictal epileptiform discharges and photoparoxysmal response to EEG [24], can be a replacement for valproates in the treatment of JME.

In 2007, a study [25] was conducted on 30 patients treated with levetiracetam, of whom 80% achieved complete remission with levetiracetam monotherapy. In this case, the final therapeutic dosages ranged from 12 to 50 mg/kg per day. This study supports the possibility of considering levetiracetam as a first-line treatment for JME.

One of the authors of this article together with N.V. Freidkova [26] conducted a study that assessed the effectiveness of low doses of valproate and levetiracetam in the treatment of idiopathic forms of epilepsy; 13 of 23 patients had JME. At the same time, the group of patients with JME (both in combination with GTCS and without them) was the most representative in achieving the best therapeutic effect. Thus, complex therapy with the mentioned AEDs led to drug remission in 6 out of 8 patients; in 1 observation, the frequency of attacks decreased by more than 75%, and in another 1 - by more than 50%.

In another study [27] of the effectiveness of levetiracetam in monotherapy in 4 patients with JME (2 patients of whom were prescribed the drug for the first time in connection with pregnancy planning, the rest were transferred to carbamazepine therapy due to clarification of the diagnosis), the use of AEDs made it possible to achieve remission of attacks within 6 months

At the same time, according to some literature data [28], levetiracetam is not inferior in effectiveness to valproate. Domestic authors conducted an extensive retrospective study of a database of 1159 patients in the Volgograd region, of which 78 suffered from JME. The follow-up period ranged from 1 to 6 years. In 56% of cases, patients diagnosed with JME were on valproate monotherapy, in 17% of cases levetiracetam was used. The rate of achieving drug remission was 83%, while when using monotherapy with valproate - 92%, levetiracetam - 87%. Complete clinical EEG remission was achieved in 41% of cases, mainly with the use of valproate.

Also, along with the study of valproate, a prospective randomized study [29] was conducted on the use of lamotrigine in patients with the onset of JME in adulthood, which compared its effectiveness and tolerability relative to V.C. There is evidence that lamotrigine is effective and better tolerated in adult patients with JME, although the prevalence of idiosyncratic reactions may be a cause for concern.

It should be noted that modern scientific literature does not raise the question of the condition of children born to mothers with JME, as well as the role of male heredity. Let us give several examples from our practice, in particular in cases such as the one described below.

Patient L.

, 37 years old, first applied at the age of 18 after GSP, due to the fact that her menstrual cycle stopped (the attack was on the eve of the start of menstruation). The second GSP of sleep happened a week later, already against the background of menstruation. Subsequently there was only a single SHG. As for myoclonus, they recurred periodically. The patient complained of frequent disturbing dreams, for which reason phenazepam was prescribed. For the first time, when examining the patient, the EEG revealed acute-slow wave complexes of frontotemporal localization of an alternating type; the last EEG in a state of wakefulness showed an episode of generalized high-amplitude spike waves with maximum severity in the anterior parts of the brain. During all this time, the patient was pregnant three times, two pregnancies were terminated for social reasons, and one took place. As of January 2015, the child is 15 years old. He was distinguished by deviant behavior, a decrease in the level of intelligence; Until the age of 13, he had nocturnal and daytime enuresis, and studies in a special school.

Since the onset of the disease, the patient has been constantly taking Depakine Chrono 300 mg 2 times a day and lamotrigine (Lamolep) 100 mg 2 times a day. There are no convulsive attacks, but still shuddering in the morning.

It should be noted that the results of the study by K. Meador et al. [30] demonstrated a decrease in IQ (intelligence quotient) in school-age children whose mothers used VC during pregnancy by 7–10 points compared to other AEDs.

To date, a number of studies have been conducted on the long-term outcomes of using VC during pregnancy, the results of which indicate a 3-fold increase in the frequency of autism spectrum disorders and a 4-fold increase in autism in children, along with population indicators. Some studies give reason to believe that such children develop attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [31-33].

The effect of VK on the mental and physical development of children when used during pregnancy depends on the dosage, although the dose threshold has not been determined. This problem and a number of issues of pregnancy in JME against the background of VK monotherapy are discussed in detail in the article by P.N. Vlasov [34].

The presence of these problems is confirmed by the existence of cases such as the one given below.

Seizures occurred in a 6-year-old child born to a father with JME. The onset of the disease in my father began with a complex partial seizure in his sleep (automatism). He was prescribed initial therapy with carbamazepine (Finlepsin) 200 mg 2 times a day. Against this background, the patient, along with repeated complex partial seizures, developed attacks of “shuddering.” EEG showed regional and generalized spike and polyspike wave activity. Then, carbamazepine was gradually replaced by depakine 500 mg 2 times a day. Epileptic activity on the EEG regressed, and the twitching stopped. Two years later, taking into account clinical EEG remission, an attempt was made to reduce the dose of depakine to 600 mg per day with a drug concentration in the blood of 48.3-50.8 mcg/ml, however, absence activity appeared on the EEG during night sleep. When the dose was increased to 300 mg in the morning and 500 mg in the evening, there was a resumption of tremor in the hands. Complete remission was achieved with a dose of 1000 mg per day (500 mg per 2-fold dose). As for the child, the perinatal history, according to the parents, is not burdened, but it is observed by a neurologist with a diagnosis of “cerebral palsy, symptomatic epilepsy with rare convulsive seizures against the background of antiepileptic therapy.”

Unfortunately, genetic analysis was not performed in the described case, so the possible contribution of a genetic factor remains unproven. Another important, but unresolved issue for both the patient and his family members remains the issue of further prognosis of the disease.

In the work of J. Gaithner et al. [35], based on an analysis of patients observed for at least 25 years, unfavorable prognosis factors were identified: onset with GSP preceding myoclonus, failure of therapy and polytherapy. Contrary to conventional wisdom, long-term treatment is not necessary, except for those patients who have these unfavorable prognosis factors. At the same time, in our studies of 30 patients, discontinuation of AEDs after a 5-year drug remission was possible only in 9; in the remaining cases, a relapse occurred. It is possible that this phenomenon is to some extent associated with the late start of adequately selected therapy. According to our observations, over the past 5 years, there have been 3 cases out of 20 with complete clinical, drug and EEG remission during treatment with VK and/or levetiracetam.

In the study by K.Yu. Mukhina et al. [16] in 106 patients with JME, clinical remission was achieved in most cases (89.6%), and clinical EEG - in 22%. The majority of patients (79%) used monotherapy, the most frequently used was VK (56%), and less commonly, levetiracetam (13%). Unfortunately, despite the high effectiveness of treatment, the authors note a high percentage (92%) of relapses, most often at the stage of dose reduction by more than 50% and during the first year after discontinuation. The authors attribute this to such reliable factors as lack of sleep (23.5%), self-cessation, dose reduction or skipping AEDs, and replacement with generics (21%).

Difficulties in social adaptation, unusual lifestyle and poor cooperation with doctors in patients with JME were first mentioned by D. Janz and W. Cristian [2]. Similar changes, reaching the level of mental disorders, were registered in 25.6% [36, 37].

Since the peculiar mental disorders in patients with JME are associated with cognitive impairment due to the frontal lobes [20, 38], Brazilian authors undertook a special study in this direction on a contingent of 42 patients with an undoubted diagnosis of JME and 42 individuals in the control group using a battery of tests. The data obtained showed that patients with JME have worse adaptation in 2 significant aspects of life - work and family relationships, however, this factor is not correlated with cognitive impairment, but with a high frequency of attacks and impulsivity [39].

A significant factor for the patient and his relatives is the early prognosis of the disease. The authors of one of the studies [40] studied sensitivity to eye closure in JME and the effectiveness of prognosis in 76 patients with a minimum follow-up period of one year. 15.8% had a poor prognosis due to resistance to adequate AEDs, 19.7% were pseudo-resistant (i.e., mistreated), and 64.5% had a good prognosis. They also studied sensitivity to eye closure. It was found only in 4 (5.3%) patients and only in those with a poor prognosis. Thus, photosensitivity is likely to be a factor that worsens prognosis.

There are data in the literature [41] regarding the relationship between the photoparoxysmal response to EEG and optical coherence tomography data. In a group of patients with a photoparoxysmal response to EEG, an increase in the thickness of the retina nerve fiber layer

both eyes and the choroid of the right eye. The retinal thickness of both eyes was significantly less. The authors believe that these microstructural features may be associated with photosensitivity in patients with JME. Other studies [40] have shown that eye closure sensitivity (ECS) in patients with JME is a rare EEG finding and cannot be a reliable marker of poor prognosis.

It is known that a violation of cortical plasticity plays one of the main roles in the pathogenesis of JME. A group of Italian scientists [42] studied synaptic plasticity of the motor cortex using the method of paired associative stimulation in patients with JME and identified corresponding changes.

The data presented indicate positive changes in the diagnosis and treatment of JME. However, despite the characteristic clinical picture of the disease and the progress of modern research methods, as well as extensive clinical experience, the issue of diagnosing this form of epilepsy remains a problem for neurologists. Factors that aggravate the prognosis have been identified: a combination of myoclonus with GTCS, the presence of mental disorders, photosensitivity, lack of proper response to adequate AEDs. At the moment, the gender aspect of the disease still remains open, especially in relation to therapy. It is also necessary to accumulate scientific information about children born to mothers with JME and the role of paternal heredity.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Differential diagnosis

If myoclonus begins in the first year of life, it must be differentiated from cryptogenic infantile seizures (CS). DS are clinically different from benign myoclonus: they are more severe and include tonic convulsions throughout the body, which is never observed in SDMED; single seizures are always combined with serial seizures in a given child; the occurrence of long serial spasms occurs after waking up. SDs then show the typical pattern of short tonic contractions on EEG, which is well described by Rusco and Vigevano (1993); Prolonged myoclonus rarely occurs. Ictal EEG variable: sudden intermittent hypsarrhythmias leveled off by superimposed fast rhythms, a large slow wave followed by leveling off or no visible change. The onset of DS is associated with behavioral changes, difficulty in speech contact, and a slowdown in psychomotor achievements.

The interictal EEG always has pathological signs: true hypsarrhythmia, or modified hypsarrhythmia, or focal disturbances; they do not detect individual or short bursts of bilateral synchronous SV or SDMED.

If psychomotor development and EEG are within normal limits on several examinations performed during wakefulness and sleep, seizures resembling DS should suggest the diagnosis of benign nonepileptic myoclonus, as described by Lombroso and Feuerman (1977). These patients even have ictal EEG without pathological changes (Drave et al., 1986; Pashats et al., 1999).

In the first year of life, myoclonic epilepsy of infancy may develop; it always begins with prolonged and frequent febrile seizures, and not with individual myoclonic seizures. In the second year, psychomotor development slows down.

If myoclonus begins after the first year of life, cryptogenic Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (CLG) may be suspected. In LGS (Byman and Dravet, 1992), the seizures are mainly not myoclonic, but myoclonic-atonic, and more often tonic, leading to sudden falls and injuries. Their EEG pattern is heterogeneous, and in the ictal period the high-amplitude either levels off, or high slow-wave activity is determined, followed by low-amplitude waves. At the very beginning, interictal EEGs may be normal, but later typical diffuse discharges of slow CO may appear. Typical electroclinical signs during sleep may be delayed in time. The diagnosis is based on the rapid association of seizures of different types, such as atypical absence seizures and axial tonic seizures, persistent behavioral disturbances and the emergence of new skills and the ineffectiveness of antiepileptic drugs.

If myoclonic seizures are isolated or associated with PEP, a diagnosis of myoclonic astatic epilepsy of early childhood (EMAI) should be considered, although in this syndrome myoclonic astanic seizures rarely begin before age 3 years (Douze, 1992). There are two significant differences: 1) the clinical aspect of seizures with stupor, which is not observed in SDMED (Guerrini et al., 1994); 2) EEG signs are also different: SV and PSV are more numerous, grouped into long flashes, connected by a typical theta rhythm over the centro-parietal zones. But some patients should probably be classified as SDMED. Similarly, Delgado-Escueta et al. (1990) included in the study or patient group, probably under the name of myoclonic epilepsy of childhood (MECD), cases of both EMAP and SDMED.

Finally, other epilepsies that begin in the first three years of life, in which myoclonus is the main seizure type and which have a variable prognosis, should be considered. They are heterogeneous: a combination of seizures of other types, persistent focal abnormalities on the EEG, delayed psychomotor development in the past, poor response to treatment, unclear prognosis (Drave et al., 1992).

Clinical examination of the patient in order to make a diagnosis.

This examination is quite simple. It requires a careful history and repeated video-EEG recordings to demonstrate the presence of MP with generalized SV discharges, spontaneous or those promoted by drowsiness, noise, contact, or IRS. Sleep recordings can show weak activation of discharges and focal disturbances. Neuroimaging is useful to confirm the absence of brain damage, but is not necessary in the presence of typical symptoms. A neuropsychiatric examination is more useful for checking psychomotor development and tracking the course of the disease.