Hemifacial spasm (facial hemispasm, Brissot's disease) is a symptom complex of unilateral hyperactive dysfunction of the facial nerve, manifested by voluntary contractions of the muscles of half the face, caused by compression of the facial nerve root in the area of its exit from the brain stem. According to American authors, hemifacial spasm occurs in approximately 0.8 cases per 100,000 population per year. Hemifacial spasm occurs more often in women (14.5 cases per 100,000), usually in the elderly. In men, hemispasm occurs in 7.4 cases per 100,000.

Our specialists

Tarasova Svetlana Vitalievna

Expert No. 1 in the treatment of headaches and migraines. Head of the Center for the Treatment of Pain and Multiple Sclerosis.

Somnologist.

Epileptologist. Botulinum therapist. The doctor is a neurologist of the highest category. Physiotherapist. Doctor of Medical Sciences.

Experience: 23 years.Derevianko Leonid Sergeevich

Head of the Center for Diagnostics and Treatment of Sleep Disorders.

The doctor is a neurologist of the highest category. Vertebrologist. Somnologist. Epileptologist. Botulinum therapist. Physiotherapist. Experience: 23 years.

Bezgina Elena Vladimirovna

The doctor is a neurologist of the highest category. Botulinum therapist. Physiotherapist. Experience: 24 years.

Palagin Maxim Anatolievich

The doctor is a neurologist. Somnologist. Epileptologist. Botulinum therapist. Physiotherapist. Experience: 6 years.

Mizonov Sergey Vladimirovich

The doctor is a neurologist. Chiropractor. Osteopath. Physiotherapist. Experience: 8 years.

Drozdova Lyubov Vladimirovna

The doctor is a neurologist. Vertebroneurologist. Ozone therapist. Physiotherapist. Experience: 17 years.

Zhuravleva Nadezhda Vladimirovna

Head of the center for diagnosis and treatment of myasthenia gravis.

The doctor is a neurologist of the highest category. Physiotherapist. Experience: 16 years.

Hemifacial spasm (HFS) is a disorder characterized by painless, involuntary unilateral tonic or clonic contractions of the facial muscles innervated by the ipsilateral facial nerve [106, 108].

In 1875, F. Schultze [83] described the clinical picture of HFS, the cause of which was an aneurysm of the left vertebral artery. A detailed description of the clinical picture of HFS was made in 1894 by the French neurologist E. Brissaud [19]. Already in the 19th century, HFS was considered as a separate nosological unit and stood out from the group of other facial hyperkinesis. Over the past 100 years since the publication of classical descriptions of HFS, the etiology of this disease has been identified and effective treatment methods have been developed.

In 2004, N. Tan et al. [99] showed 203 family doctors a video recording of a patient suffering from HFS: only 9.4% of them were able to correctly diagnose and 46.3% of doctors were able to correctly choose the management tactics for such a patient. Primary care doctors are poorly informed about this disease and cannot prescribe adequate treatment and refer the patient to the appropriate specialist. In the modern Russian-language scientific literature there is a limited number of publications devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of HPS [4, 9]. In modern manuals on neurology and neurosurgery, ideas about etiology and pathogenesis are not fully reflected.

In classic cases, an attack of HFS begins with rare contractions of the orbicularis oculi muscle, then, gradually progressing, the spasm affects the entire half of the face, the frequency of muscle contractions increases and reaches such an extent that the patient cannot see with the eye of the affected side (typical HFS). With atypical HFS, the attack begins with contraction of the cheek muscles, then the spasm spreads up the face [50, 80]. Attacks of spasms occur spontaneously and can persist even during sleep; they are provoked by overwork, stress, and anxiety [31].

In 1905, the neurologist J. Babinski described the paradoxical synkinesis of the facial muscles during HFS: “On the side of the spasm of the m. orbicularis oculi

contracts, the eye closes, at this time the inner part

of m.

frontalis on the affected side also contracts, which leads to the raising of the eyebrow during the closure of the palpebral fissure” [15]. J. Devoize [28] called this symptom “the other Babinski’s sign” (“another Babinski’s symptom” to distinguish it from Babinski’s symptom when the pyramidal tract is affected); some authors consider it pathognomonic for HPS. The described synkinesis is characteristic of HFS and does not occur in other facial hyperkinesis [90].

The disease usually first appears between 40 and 50 years of age [14, 31]. HFS is a chronic disease, the rate of spontaneous remission is less than 10% [31]. Months or years after the onset of the disease, patients may develop moderate paresis of the facial muscles on the affected side [51]. Muscle weakness is detected in 47% of cases in the muscles of the eyelids and in 77% when assessing the strength of other facial muscles [34]. Bilateral HPS is extremely rare (0.6-5%) [94, 108].

Other cranial nerves may be involved in the pathological process. HPS is often combined with dysfunction of the auditory nerve - an anomaly of the acoustic reflex of the middle ear is observed in 50% of patients with hemispasm [71], hearing loss to varying degrees is detected in 15% [31]. Sometimes HFS is accompanied by low-pitched noise in the ipsilateral ear, this is due to the involvement of the m.stapedius

, which contracts synchronously with the facial muscles [84]. In 5% of cases, HPS can be combined with trigeminal neuralgia [63, 79, 108]. Cushing called this syndrome "painful tic convulsif" - "painful facial tic." A combination of HPS with blepharospasm has been described [91].

According to the Minnesota Epidemiological Study [14], conducted in 1960-1984, the prevalence rate of HFS was 7.4 per 100,000 male population and 14.5 per 100,000 female population; The mean annual incidence rate, age-standardized for the white population in the United States in 1970, is 0.74 per 100,000 for men and 0.81 for women. The incidence rate and prevalence rate of the disease are highest in the age group from 40 to 79 years. Note that this study included patients with both primary and secondary HPS. According to N. Nilsen et al. [76], in Norway the prevalence of HFS is 9.8 per 100,000 population. A higher incidence of HFS has been noted [12] among people of the Mongoloid race compared to Caucasians. Such differences may be associated with features in the structure of the skull, in particular the size of the posterior cranial fossa [54]. However, epidemiological studies have not been conducted to identify the prevalence of HPS in people of the Mongoloid race.

Despite the fact that the clinical picture of HPS was described at the end of the 19th century, the cause of this disease remained a mystery to researchers for many years. In the 50-60s of the 20th century, there was an active discussion about the “peripheral” or “central” origin of GFS.

R. Siekert [86] and E.P. Fleiss [7] described symptomatic HFS in tumors of the tympanojugular glomus. In the above observations, richly vascularized glomus tumors affected the facial nerve, which resulted in the development of HFS. S.N. Davidenkov [3] and E.P. Fleiss [7] believed that facial hemispasm is of a peripheral nature, and there are no symptoms of central nervous system damage. R. Wartenberg [107] studied the “central” genesis of HPS. According to his hypothesis, HFS is based on changes in the functional state of the nucleus of the facial nerve and supranuclear structures. However, all these concepts did not make it possible to explain the features of the clinical picture of HFS and to develop effective treatment methods on their basis.

In 1947, E. Camblell and C. Keedy [20], and then E. Lain and P. Nyrac [58] suggested that the cause of hemifacial spasm is compression of the facial nerve by ectatic vessels of the base of the brain. In 1962, this guess was confirmed during surgical exploration of the posterior cranial fossa in patients with HFS [35, 36].

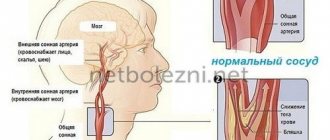

The priority in the development and popularization of the theory of microvascular compression as a cause of neurovascular compression syndromes of cranial nerves (trigeminal neuralgia, HPS, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, spastic torticollis) belongs to the American neurosurgeon P. Jannetta [47-49, 51]. The theory of microvascular compression, in his opinion, is based on a neurovascular conflict - a “conflict” between the root of the cranial nerve at the site of its entry and exit from the brain stem with the adjacent vessel.

The main pathogenetic factor in the development of microvascular compression syndromes of the cranial nerves is the mechanical effect of a pulsating vessel on the nerve trunk with the subsequent spread of pathological impulses and the development of its paroxysmal functional activity (paroxysmal facial pain - when affecting the trigeminal nerve, paroxysmal contraction of the facial muscles - when affecting the facial nerve) [49]. Compression factors are usually atherosclerotic aberrant or ectatic arteries. A conflict of a nerve with an arterial vessel (anterior or posterior inferior cerebellar arteries, vertebral or basilar arteries) is more often observed; a conflict of a nerve with a venous vessel is rarely observed [64].

With the development of neuroimaging methods, the introduction of surgical microscopy into widespread practice and, as a consequence, the improvement of surgical techniques, compression of the facial nerve by ectatic vessels began to be considered the main cause of HFS, and the concept of neurovascular conflict in the genesis of microvascular compression syndromes began to gain more and more supporters [1, 2 , 5, 6, 8, 29]. According to P. Jannetta, compression of the nerve occurs in the zone of entry and exit of the nerve root (REZ - root exit/entry zone). It is important that in the zone of root exit, thinner central glial myelin transforms into thick, peripheral “Schwann myelin” (this anatomical feature was first described by H. Obersteiner and E. Redlich in 1894 - the Obersteiner-Redlich zone) [77]) .

In typical HPS, the vessels compress the anterocaudal region of the VII/VIII nerve complex, and in atypical HPS, compression is localized in the posterostral region. The features of the neurovascular conflict zone explain the differences in the clinical picture of typical and atypical HPS [50]. The contact of vessels with the exit zone of the vestibular nerve root leads to the appearance of complaints of dizziness in the clinical picture, and when the vessels come into contact with the exit zone of the cochlear nerve root, complaints of hearing loss and tinnitus appear [50]. Combined compression of the roots of the V and VII nerves is possible; in this case, HPS will be accompanied by facial pain (a combination of trigeminal neuralgia and HPS) [79].

Although the generally accepted cause of neurovascular conflict is vascular compression, a number of studies have been published that provide data that do not fit into the classical theory of P. Jannetta. It should be noted that the subject of discussion is the possible localization of areas of neurovascular conflict, and not the concept of neurovascular compression at its core, which is recognized by most researchers.

H. Ryu et al. [81]. distal portion. There are several descriptions [33, 72, 109] of cases of identifying a zone of neurovascular conflict outside the zone of root exit.

D. De Ridder et al. [27] suggested that the frequency of microvascular compression syndromes of cranial nerves in the population depends on the length of the central segment of each of them. Since the central segment of the trigeminal nerve has the greatest length [59] and is then followed in descending order by the facial, glossopharyngeal and vestibulocochlear nerves, accordingly, trigeminal neuralgia will most often occur, and compression of the vestibular nerve will occur less frequently. Clinically significant is compression of the nerve throughout the “central” segment (the segment of the nerve covered with “central” myelin), and not just compression in the REZ zone [27]. A similar point of view was previously expressed by T. Leclerq [61] and A. Moller [66].

This hypothesis can be confirmed by the data of M. Sindou et al. [87]. These investigators analyzed the results of 579 microvascular decompressions for trigeminal neuralgia. It turned out that compression in the area of the root exit occurred only in 52.3% of cases, in its middle portion - in 54.3%, in the area of the Meckel cavity - in 9.8%.

Currently, the theory of microvascular compression makes it possible to explain the clinical and neurophysiological features of HFS. Based on this concept, an effective method for treating HFS has been developed—microvascular decompression surgery. This fact, like no other, testifies in favor of the theory developed by P. Jannetta. Undoubtedly, it requires further development and addition.

Some authors believe that neurovascular conflict is one of the factors in the genesis of HFS and other microvascular compression syndromes. Thus, A. Kuroki and A. Moller [57] consider primary nerve injury, accompanied by local demyelination, in combination with vascular compression in this area as a combination of trigger factors in the development of hemifacial spasm. These judgments also complement the theory of microvascular compression and do not contradict it.

Some studies highlight the association between hypertension and HPS. Arterial hypertension is considered a risk factor for the occurrence of HPS, since hypertension contributes to the progression of atherosclerotic changes in blood vessels, which leads to their ectasia and pathological tortuosity, predisposing to the development of vascular compression. In turn, it is assumed that compression of the ventrolateral parts of the medulla oblongata by ectatic vessels can lead to arterial hypertension [25, 52, 76, 93].

The development of MRI and MR angiography has provided additional evidence in favor of the theory of neurovascular conflict, since direct visualization of the nerve root and the vessel compressing it has become possible. High-resolution MRI and MR angiography are quite sensitive methods for detecting neurovascular conflict [10, 38, 92].

Sometimes HPS is caused by space-occupying formations of the cerebellopontine angle (tumors, vascular malformations, aneurysms) [24, 100, 104]. Space-occupying formations alter neurovascular relationships, leading to displacement of blood vessels and their contact with nerve roots, or have a direct compressive effect on the facial nerve. Hemispasm can also be caused by multiple sclerosis [101], lacunar infarction in the pontine region [105], inflammatory diseases of the middle ear [60], and deformations of the skull bones (for example, in Pagett's disease) [45].

Thus, depending on the etiology, HFS can be divided into primary

, the causes of which are neurovascular conflict in the area where the nerve exits the trunk, and secondary - caused by other pathological processes. The division of HPS into primary and secondary is currently generally accepted in the literature [22, 25, 108]. The use of the term “idiopathic HFS” is incorrect, since the cause of the spasm has been established.

Currently, there are two main hypotheses for the pathogenesis of HPS. The central hypothesis explains the symptoms of HFS by changes (hyperexcitability) of the nucleus of the facial nerve [67, 68], the peripheral one - by damage to the myelin sheath and ephaptic transmission of nerve impulses between different nerve fibers [74, 75].

V. Nielsen in 1984 [74, 75] put forward the hypothesis of ephaptic or ectopic transmission: as a result of nerve compression and subsequent demyelination, “false” synapses are formed, through which ectopic activity can be triggered due to mechanical irritation in adjacent nerve fibers. He showed that this mechanism underlies the electrophysiological phenomenon, the so-called abnormal muscle response in HPS. This phenomenon disappears after decompression of the facial nerve using microvascular decompression [51, 74, 75].

A. Moller and P. Jannetta [67-69] believe that the main pathological processes in HFS occur in the nucleus of the facial nerve in response to peripheral stimuli (vascular compression). K. Digre and J. Corbett [29] put forward an alternative hypothesis, according to which, as a result of compression, aberrant regeneration occurs in the facial nerve, which leads to the restructuring of axonal fibers.

In the 70-80s, CT and MRI were considered as auxiliary diagnostic methods and served mainly to exclude organic pathology (tumors, vascular malformations, aneurysms), which could cause secondary HPS, or to identify compressing vessels of large diameter (for example, ectatic vertebral arteries) [30, 89, 100]. With the advent of high-field MR tomographs with high resolution and the subsequent development of special software (3D reconstruction programs), the capabilities of the method have expanded significantly. The possibility of non-invasive visualization of neurovascular conflict has become possible [10, 38, 92].

Numerous studies have shown that MRI and high-resolution MR angiography are quite sensitive methods for detecting neurovascular conflict [39, 92]. Y. Nagaseki et al. [73] demonstrated that detection of small-diameter vessels (anterior and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries) was possible in 75.9%, and large-diameter vessels (vertebral artery) in 100%; there were no false-negative results. The authors emphasize that the diagnostic capabilities of MRI depend on the correct projection (oblique sagittal MRI projection) and the correctly selected pulse sequence.

At the present stage of development, MRI in most cases makes it possible to identify the cause of HFS (tumor, aneurysm, vascular malformation in the area of the cerebellopontine angle, focus of demyelination, focus of lacunar infarction) and visualize the neurovascular conflict, i.e. distinguish between secondary and primary GFS.

Although the key to diagnosing HPS is primarily a neurological examination, electromyography (EMG) also provides a lot of useful information. There is evidence that HPS has pathognomonic electromyographic patterns [32, 69]. R. Hjorth and R. Willison [43] described two main EMG patterns in HPS. The first is short, quick tics (twitching), which are simultaneously observed in various muscle groups of half the face and are often accompanied by blinking movements. The EMG records isolated bursts of repeated high-frequency discharges. Each series includes from 2 to 40 discharges from one motor unit. The intervals between series of discharges vary greatly, their frequency is 200-250 Hz, but can reach 350-400 Hz. Attenuation of the motor unit action potential during a volley of discharges is often observed. The second characteristic, but less common type of movement abnormality is prolonged, irregular, fluctuating muscle contractions, which lead to forced closure of the eye for several seconds. Despite the fact that in this situation it is not possible to record the signal from individual motor units in isolation, the researchers were able to establish that the excitation of the motor units occurred irregularly and with a lower amplitude than in the first pattern [43].

With HFS, another electroneurophysiological phenomenon can be observed: with electrical stimulation of one of the branches of the facial nerve, contraction of the facial muscles innervated by other branches of the facial nerve occurs, for example, with stimulation of the temporal branch, contractions of m. mentalis

. This phenomenon is called the abnormal muscle response phenomenon or the lateral spread phenomenon [67, 68]. It is believed that this effect is due to the cross-transmission of antidromic activity that occurs as a result of microtrauma to the nerve during a neurovascular conflict [74, 75]. This phenomenon is used not only for diagnosing HPS, but also for intraoperative monitoring when performing MIA [39, 51, 78, 88].

HFS should be distinguished from a number of other facial hyperkinesis [29, 108]. R. Blair and H. Berry [18] cite the following diseases and syndromes with which a differential diagnosis must be made: essential blepharospasm; facial myokymia (pseudofasciculations), including tic (psychogenic facial spasm), focal cortical seizures affecting the facial muscles, aberrant regeneration of nerve fibers after facial nerve injury or Bell's palsy, delayed (tardive) dyskinesia (as a complication of taking antipsychotics).

Some authors [98, 102] consider it possible to include Meij’s syndrome (a combination of blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia) in this list.

To treat HFS, drugs from different pharmacological groups are used: carbamazepine [11], clonazepam [41], gabapentin [23], levetirace [26], baclofen [82]. However, their effect was studied in small samples of patients, without placebo control. Therefore, the long-term effect of such treatment seems rather doubtful [98]. Due to the fact that the pathology in question requires constant use of medications in fairly high doses, it is necessary to take into account their side sedative effect, which cannot but affect the quality of life of patients.

Botulinum toxin type A has proven itself well in the treatment of HFS [17, 95]. The effectiveness of this drug was established by W. Jost and A. Kohe [53] in a study conducted taking into account the principles of evidence-based medicine: the effect of botulinum toxin was studied in large samples (up to 2000 patients) in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The drug is administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly into the affected muscles. The use of botulinum toxin in the early stages of the disease is especially promising.

However, injections must be performed on average every 3-4 months [106], the cost of the drug is quite high, and it requires strict adherence to storage rules. The effectiveness of treatment (significant regression of symptoms) is observed in 70-75% [98, 110]. In 2-14%, complications such as ptosis, keratitis, diplopia, epiphora (retention lacrimation), drooling, strabismus (strabismus) are observed [53, 55]. A. Wang, J. Jancovic [106], observing 110 patients, described transient paresis of the facial muscles (23%), ptosis (15%). Assessing the results of treatment with botulinum toxin, one can still note their lack of durability, and the high cost limits its use [78, 98].

Attempts at surgical treatment of HFS were made at the beginning of the 20th century. Before the advent of microvascular decompression methods, treatment of HFS was limited to applying severe or moderate therapeutic destructive effects to the peripheral part of the facial nerve or parts of the nerve in the region of the cerebellopontine angle. Complete or partial destruction of the peripheral part of the facial nerve or its branches was performed surgically or by injection of glycerol or ethanol [40], but instead of nerve spasm, its paresis sometimes developed [65]. Moreover, after 3-6 months, a recurrence of spasm usually occurred due to nerve regeneration. Myectomy was also performed - unilateral resection of m. orbicularis oculi

and

m.

corrugator supericiliaris [37]. Currently, extracranial destructive procedures are practically not used due to their low effectiveness [46].

In 1960, W. Gardner [36] published a case of recovery from HFS after neurolysis of the facial nerve in the area of the internal auditory canal. By 1962, he had experience in the surgical treatment of 19 patients, all of whom had undergone neurolysis of the VII nerve in the region of the cerebellopontine angle. In 7 cases, compression of the facial nerve by the loop of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery or the internal auditory artery was detected [36]. Later, W. Scoville [85] successfully treated HFS in one patient by displacing the peripheral artery from the facial nerve in the area of the cerebellopontine angle, but the patient lost hearing after the operation.

P. Jannetta developed and popularized microvascular decompression for neurovascular syndromes. He performed his first decompression during HFS in February 1966, and in 1970 his first article on this topic was published [47]. The operation consists of installing a protector (Teflon is usually used) between the conflicting vessel and the nerve, which eliminates the chain of pathological impulses. In 1999

M. McLaughlin, P. Jannetta et al. in a corresponding publication [64], they summarized more than 30 years of experience in performing microvascular decompression for neurovascular syndromes, citing the results of 4400 operations.

Other scientific centers have also accumulated sufficient material on the use of microvascular decompression in HFS, allowing us to assert that this method is more effective in the treatment of primary facial spasm, the cause of which is a neurovascular conflict, reaching 86-93% [1, 13, 16, 21, 56 , 64]. F. Barker et al. [16] reported complete regression of HFS symptoms in 86% of 612 patients, partial effect was achieved in 5% of cases with an average follow-up period after therapy of 8 years; according to long-term results obtained by R. Illingworth et al. [44] (average follow-up period 8 years), the effectiveness of the procedure was 92.2% (in 83 out of 86 patients).

The recurrence rate of HFS after microvascular decompression, according to various authors [103, 108, 109], is up to 20%. In a work devoted to the study of relapses of HFS after microvascular decompression, J. Tew and P. Troy [103] showed that if a patient does not have a relapse after surgery for 2 years, then the probability of developing a recurrent spasm is less than 1%, the relapse rate in their work is approaching 7%. The most common complications after such an intervention are permanent or transient dysfunction of the vestibulocochlear and facial nerves. Complete loss of function of the vestibulocochlear nerve occurs in 1.6-2.6%, moderate hearing loss in 0.6-0.7% of cases [16, 64]. Paresis of the facial nerve in various series occurs in 3.4-4.8%; As a rule, facial nerve dysfunction is transient, and when assessing the long-term results of microvascular decompression, in most cases, complete regression of prosoparesis is noted [78]. To avoid dysfunction of the VIII nerve, intraoperative monitoring of acoustic brainstem evoked potentials is used [70, 88]. Less common are dysfunction of the caudal group of cranial nerves, infectious complications, wound liquorrhea, hemorrhages in the trunk and cerebellum. Works have been published to evaluate complications in large samples of patients. When analyzing the results of 4400 microvascular decompressions for neurovascular compression syndromes of the cranial nerves, M. McLaughlin, P. Jannetta et al. [64] noted the following frequency of complications: in the group of patients operated on before 1990, cerebellar damage 0.87%, hearing loss 1.98%, liquorrhea 2.44%. In the group of patients operated on after 1990, the number of complications decreased: 0.45% of patients had cerebellar damage, 0.8% had hearing loss, and 1.85% had wound liquorrhea [21, 64]. It should be noted that for surgeons who perform a large number of operations, the incidence of complications is minimized [21, 64, 98].

The basis for assessing the results of treatment for HFS is primarily a clinical assessment of the regression of hemispasm symptoms. In this regard, a gradation of relevant changes was proposed. For example, V. Marneffe et al. [62] suggest that the result be considered “excellent” if the spasm completely disappears, “good” if the regression is more than 80%, “satisfactory” if the regression is from 20 to 80%, and the result is considered “unsatisfactory” if the symptoms are relieved by less than 20%. . T. Iwakuma et al. [46], P. Jannetta [49, 51], R. Auger et al. [13] used a 6-level scale to evaluate the results, highlighting “excellent”, “good”, “satisfactory”, “unsatisfactory”, “poor” and “recurrent”. In all rating systems, “excellent” is the result of complete disappearance of symptoms, “good” is the disappearance of 75-80%. The goal of treatment is, of course, to achieve “excellent” or “good” results.

Despite the fact that HFS does not pose an immediate threat to the lives of patients, it significantly worsens its quality, limiting their professional and social activity, causing psychological discomfort [51, 96]. More than 75% of patients experience discomfort due to their disease, 15-65% suffer from depression. HFS impairs vision in 60% of patients and interferes with work activity in 36% of patients [12].

To assess the quality of life of patients with HFS, both “general” (SF-36) and special Hemifacial spasm scales (HFS-7 and HFS-8) are used. The validity and reliability of the latter was shown in the works of E. Tan et al. [97]. The HFS-7 and HFS-8 have 7 or 8 questions and are very quick to complete. K. Heuser et al. [42] demonstrated the use of this tool to evaluate the effectiveness of microvascular decompression for HFS and found that this procedure significantly improved the quality of life of patients.

Thus, the cause of primary HPS is compression of the facial nerve in the area where it leaves the trunk by vessels, secondary HPS is most often caused by pathological processes in the area of the cerebellopontine angle. The diagnosis of HFS is established clinically and using these additional methods (EMG, MRI). Differential diagnosis must be made with a number of other facial hyperkinesis. The basis of modern ideas about the pathogenesis of primary HFS is the theory of microvascular compression, the cornerstone of which is the concept of neurovascular conflict. The most effective treatment for primary HFS is microvascular decompression of the facial nerve. Methodologically, this procedure is well developed. The second most effective treatment method is botulinum toxin injections. This method has a number of disadvantages, but it may be preferred by patients who categorically do not accept surgical treatment methods. The determining criteria in assessing the results of treatment for HFS are the degree of clinical regression of hemispasm and improvement in the quality of life of patients.

Read also

Treatment of spasticity

Spasticity is an excessive increase in muscle tone, the cause of this condition can be a stroke, traumatic brain injury, spinal injury, spinal cord problems, neuroinfection, multiple…

Read more

Hyperhidrosis

Hyperhidrosis is a condition that is manifested by excessive, inadequate sweating due to increased activity of the sweat glands. It happens that a person sweats so profusely that his clothes get wet very quickly, from his hands...

More details

Spasmodic torticollis (cervical dystonia)

This is a chronic disease that occurs as a result of impaired muscle tone in the neck and is manifested by incorrect head position or forced rotation of the neck muscles. According to statistics, this disease...

More details

Blepharospasm

Blepharospasm is a chronic disease characterized by involuntary squinting of the eyelids due to increased tone of the orbicularis oculi muscles. Most often, the causes of blepharospasm are extremely difficult to establish or...

More details

Torsion dystonia

This is a chronic nervous disease that manifests itself in the form of uncontrolled tonic muscle contractions, which can result in pathological postures and hyperkinesis. Torsion dystonia…

More details

Drug treatment of hemifacial spasm

Treatment of hemifacial spasm most often begins with drug therapy. Typically, drugs from various pharmacological groups are used: baclofen, carbamazepine, gabapentin, clonazepam. However, due to the fact that facial hemispasm requires regular use of the above drugs, it is necessary to take into account their side effects, which cannot but affect the lives of patients. The effect of drugs from these pharmacological groups was studied in small samples of patients, without placebo control, so it seems doubtful. Botulinum toxin type A is used quite widely in the treatment of HFS, which is injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly into the affected muscles. Significant regression of symptoms is observed in 70-75% of cases, however, injections must be performed every 3 months, the cost of the drug is high, and in 2-14% of cases complications such as facial muscle paresis, ptosis, keratitis, diplopia, drooling, and strabismus are observed.

Is it possible to undergo implantation for bruxism?

Only on condition that an integrated approach is applied to implantation and subsequent installation of the prosthesis. In order for your new teeth to serve you for a long time, we carefully plan the entire course of treatment from start to finish: we conduct in-depth diagnostics, identify related problems that may affect the result, take measures to eliminate them, and step by step work through the entire course of the operation and prosthetics.

For example, our patients often experience bruxism and problems with the temporomandibular joints due to the fact that the dental system has not been working properly for a very long time - the teeth were destroyed, the load was distributed unevenly. In itself, the return of all teeth through complex implantation is already a treatment for such conditions, since we think over dentures taking into account the correct functioning of muscles and joints, normal closure of the dentition, etc. But the body will need time to adjust to normal functioning. And that is why in cases of bruxism we are taking additional measures - increasing the number of implants installed for the entire jaw, making prostheses reinforced with a frame and made from more durable materials, and making protective soft mouth guards.

But if bruxism in adults cannot be cured only by dental methods, since the problem is not with the jaw system, but with the same psychosomatics, then we refer the patient for treatment to a specialized specialist - and return to dental restoration afterwards. We care about your health and do everything to ensure that the achieved treatment results last not just for a couple of years, but throughout your entire life.

Etiology

Damage or irritation of the root emerging from the hindbrain leads to the development of hemifacial spasm. The conducted studies indicate that impacts on any fragment of the central segment of the facial nerve can lead to pathology, and not, as previously thought, only at the site of its exit.

Unfavorable factors that provoke HFS include:

Aneurysms of cerebral vessels. The walls of arteries or veins may bulge due to their pathological stretching. In this regard, the facial nerve is under compression. Excessive compression of this structure leads to prolonged irritation of the nerve fibers, which in response send impulses to the facial muscles.- Neuralgia or neurovascular conflict. It is a consequence of individual characteristics and anatomical location. The nerve root may be in close proximity to nearby arteries, the pulsation of which causes irritation. Constant and prolonged exposure to this structure leads to contractions of the facial muscles.

- Destruction of the myelin sheath of the nerve. The sheath covering the nerve can undergo destructive changes and cause disruption of signal transmission along the nerve fiber, during which a hyperthermic reaction occurs.

- Tumors and tumor-like formations. Pathological growths in the form of tumors and cysts lead to displacement and compression of the nerve, which provokes a response from it in the form of spastic contractions.

- Lacunar infarction. A cavity, or lacuna, forms in the area affected by ischemia due to a stroke. It can also push back the root or central segment of the facial nerve, which will lead to muscle spasm.

Prevention of bruxism: how to help yourself

By prevention we mean measures that prevent dental hypertonicity and bruxism in adults, because without finding the cause and monitoring a specialist, treating them at home is an unsafe activity, as with any disease. So if you notice alarming symptoms, your first step is to get diagnosed and get a plan to comprehensively eliminate this problem.

You may need the help of several specialists (neurologist, dentist, gastroenterologist, ENT doctor, psychotherapist), because bruxism occurs in different people for very different reasons. You may be prescribed courses of physiotherapy, taking certain medications (for example, magnesium supplements), but all this, of course, is very individual.

Self-help measures are helpful if you discuss them with your doctor. For example, you can do a light relaxing massage against bruxism in the area of the chin and temples. There are also a number of exercises that can help relieve muscle spasms; it is useful to repeat them regularly before bed. Relieve general stress: sleep enough hours, walk more in the fresh air, reduce the amount of coffee and strong tea, take relaxing baths with herbs, avoid anxious situations.

All this will help consolidate the results of complex professional treatment and forget about unpleasant symptoms.

Disadvantages of treating bruxism with Botulax

It is important to choose an experienced, certified doctor who has trained and has official approval for botulinum toxin injection therapy - this is a rather complex procedure with its own subtleties. If the rules of storage, selection of dosage and administration technique are not followed, complications may occur. And if hematomas, bruises or slight swelling basically go away on their own, then difficulties with swallowing and chewing should be eliminated together with a doctor.

Our doctors have been trained and certified - treating hypertonicity with botulinum therapy in our clinic is completely safe

Indications and contraindications for botulinum therapy of masticatory muscles

Indications

- pain in the temporomandibular joint area,

- limited mouth opening,

- clicking, crunching, discomfort when moving the lower jaw,

- pathological abrasion of enamel,

- overstrain of the masticatory muscles, their soreness and heaviness,

- preparation for implantation, classical prosthetics (especially veneers), orthodontic treatment.

Contraindications

- pustular skin lesions, ulcers, acute infection in the area of the masticatory muscles,

- viral and infectious diseases in the acute stage,

- neuromuscular diseases (myasthenia gravis),

- constant use of certain medications and antibiotics,

- pregnancy and lactation period,

- bleeding disorders,

- diabetes,

- allergic reactions to the components of the drug,

- oncology and severe mental disorders.

general information

For the first time, the characteristics of this disease were given by the German doctor F. Schulz in 1875, and later in 1884, the French neuropathologist E. Brissot described it in more detail. In connection with the name of the last doctor, hemifacial spasm can be found in the medical literature as Brissot's disease.

Pathology occurs more often in women (about 1.5-2 times). The age range includes people over 40 years of age. Some medical sources indicate that Asians are more susceptible to this disease. This is associated with the ethnic characteristics of the structure of the skull.

Most often, hemifacial spasm affects one side of the face, but there are extremely rare exceptions when both sides are affected.

Choosing a sleep guard for bruxism: types and price

Firstly, there are universal and individual options: finished products are produced in factories using standard templates, and custom-made mouth guards are made exactly to your measurements.

Also, as we mentioned, mouthguards are not only night guards. The vast majority of patients suffer from teeth grinding during sleep, but a number of people cannot control jaw clenching during the day - for such cases, there are options for daytime overlays that are more invisible and do not affect pronunciation.

A mouthguard for teeth against bruxism, especially a night guard, can be bought at a pharmacy (either in Moscow or in any other city). It costs about two to three times less than a custom-made one. The quality depends on the manufacturer, and universal options have limitations in size and shape, so they simply may not fit the dentition. But the most important limitation, which patients often forget about, is that a ready-made onlay should be purchased on the recommendation of a dentist, and not self-medicated. Alas, without diagnosing and searching for the causes of spasm of the masticatory muscles, a ready-made mouth guard will do more harm than good.

Therefore, it is better if the mouth guard is made individually - based on a cast of your jaws. Individual mouthguards for bruxism, made for sleep, take into account anatomical features to the smallest detail and do not overload the teeth. And if you need to wear the veneer during the day, then it should match the shape of the teeth so that it is truly invisible when communicating. You can order such a mouthguard for bruxism in dentistry by contacting your doctor about this problem.

The doctor will also give recommendations on how long a day it is best to wear a mouth guard, how to care for it, and when the product should be replaced.

Diagnostics

Electromyography (a series of action potentials that follow in the form of short bursts; increased excitability of nerve fibers; signs of denervation of facial muscles).- Magnetic resonance imaging / magnetic resonance angiography of the brain (source of compression of the facial nerve / damage to the intrastem part of the nerve in multiple sclerosis).

Differential diagnosis:

- Benign facial myokymia.

- Essential blepharospasm.

- Facial tic.

- Postneuritic contracture due to neuropathy of the facial nerve.

- Partial epileptic seizures.

Pathogenesis

The tension and relaxation of the facial muscles depend on signals coming from the brain. As a rule, the impulses are distributed evenly and simultaneously. But when exposed to unfavorable factors, a disorder may occur that leads to the development of a hyperreaction.

The pathological focus is most often located on one side and very rarely affects the area of two facial nerves at once. In the development of hemifacial spasm, hypertension and cerebral atherosclerosis are of no small importance. They cause functional disorders, which can also affect the nervous system.

Other cranial nerves exit near the site where the roots exit, for example:

- trigeminal;

- vestibulocochlear;

- Glossopharyngeal.

So, the pathological process can cover them too. Therefore, hemifacial spasm is often accompanied by hearing disorders, neuritis or neuralgia of the trigeminal nerve; less often, the glossopharyngeal nerve is involved in the process.

Incidence (per 100,000 people)

| Men | Women | |||||||||||||

| Age, years | 0-1 | 1-3 | 3-14 | 14-25 | 25-40 | 40-60 | 60 + | 0-1 | 1-3 | 3-14 | 14-25 | 25-40 | 40-60 | 60 + |

| Number of sick people | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | 7.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.5 | 14.5 |

Why are mouthguards needed for bruxism?

Another additional way to treat hypertonicity of the masticatory muscles in adults is to wear a special protective mouth guard (they are also called a “mouth guard” or “bruxism trainer”). These are plastic and dense overlays for teeth, which are worn mainly at night, and in case of severe symptoms, worn during the day. They are made from hypoallergenic materials in a dental laboratory individually for the patient or at the factory, if we are talking about mass production.

But this is also an auxiliary measure - a mouth guard helps muscles relax, protects against tooth wear and the consequences of bruxism, but does not remove the cause of hypertonicity.

- protection of enamel from cracks, chips, increased abrasion due to involuntary clenching of teeth,

- protection of artificial crowns, dentures (including those on implants) or brace systems from damage,

- relieving tension and pain in masticatory muscles and joints,

- protection against movement and displacement of teeth due to constant pressure on them,

- gradual return of the jaws and joints to the correct position in the event of their displacement (of course, only individual mouthguards for bruxism made by a doctor work this way).