What is coordination?

The term coordination is derived from the Latin “coordinatio”, which translates as “mutual ordering”. The coordination process is the coordination of the body's muscles, aimed at the best execution of the task. As motor skills develop, coordination improves, and inertia of organs that are in constant or intermediate work is formed.

When a person is constantly in motion, systematically repeats certain movements and exercises, complicates the loads, learns something new, then motor skills are improved and the motor centers of the brain are involved, and a stable connection is established between the brain and organs. Coordination in physical education is the ability to correlate one’s own actions, organize and coordinate them.

The brain sends impulses through a network of nerves, and organs, under their influence, perform certain movements.

Not every person has such agreement. Some adults and young children sometimes move awkwardly, gesticulate awkwardly, their gait is unattractive, they are unsteady on the ground, and they have problems with the vestibular system. Therefore, it is necessary to work on coordination systematically. To do this, in addition to sports training, it will be useful to improve the individual emotional background and practice attention.

Effective activities for developing coordination

There are many training methods for coordination and development of the vestibular apparatus.

To get started, just a few simple exercises are enough:

- The right hand makes the motion of the saw, that is, “back and forth,” and the left hand makes the movement of the ax, which means “up and down.” At some point, it is necessary to change the order of movement: the second hand must perform the actions of the first, and the first, accordingly, the second.

- Hands raised up. The left one depicts a circle forward, the right one depicts a circle backward. Then the limbs move in the opposite direction.

- You can test your coordination by doing a simple exercise: extend either hand with your palm open. Next, you need to press your little finger to your palm, while the other fingers should be in an unfolded state.

- It is required to make rotational movements with your hand to the left, and at the same time describe a circle with your foot in the opposite direction. Having arrived at a positive result, you should try to do the same with both hands and feet, sitting on some surface.

Age characteristics of coordination

The ability to coordinate one’s movements is directly dependent on a person’s age:

| Age (years) | Status of indicators |

| 5 | Unsatisfactory (except for children involved in sports and music). |

| 8 | Characterized by unstable speed and rhythm of motor activity. |

| 14 | The pace and clarity in the activity of all muscle groups is manifested in connection with the completion of the formation of the entire functional system of the body. |

| 15 | There is a slight decrease in activity. |

| 17 | Age of optimal development. The body is ready for productive work, training and acquiring skills. |

Over time, all movements are automatically harmonized and the muscles are coordinated with each other, functioning in a balanced and efficient manner. During physical education lessons, schoolchildren gain knowledge in athletics, gymnastics, participate in sports games and gain primary skills in working with sports equipment. Without good coordination, you cannot expect success in any exercise.

Therefore, the educational process is aimed at developing coordination of muscle work with the desires of students. The most favorable period for working on coordination is in the elementary grades. This is due to the peculiarity of the human psyche for the childhood period of development. A child is able to perceive and understand something only after seeing and performing a certain set of movements. This is the visually effective type of thinking characteristic of childhood.

Coordination abilities

The main indicators of coordination abilities are:

- speed of reactions;

- dexterity;

- equilibrium;

- orientation in space.

For proper training of the vestibular apparatus, classes that include elements of acrobatics and gymnastics are of great importance. During these exercises, it is necessary to increase the load and speed of exercises gradually. Exercises should be varied, and the pace should be increased over time. In this type of activity, spatial orientation develops easily, because in this case both visual sensations and muscle activity are involved.

Such exercises are carried out together with explanations and instructions from the teacher. The movement of the arms and legs occurs: in turn, synchronously, sequentially. It is easiest to coordinate movements when they are performed synchronously and in the same direction. It is more difficult to perform alternating exercises. The most difficult movements are in different directions and have different names. In exercises for legs and arms, you need to take into account the increase in difficulty.

In addition to everything, you need to do exercises where the arms or legs, or the body, are worked separately, and then add exercises that connect the movement of the body, arms and legs.

Something new is always required in coordinating and maintaining students’ interest in classes. When doing exercises, you need to use original starting positions, opposite movements, mirror actions, and changing rhythms. At first, when studying orientation in space, changing the position of body parts is carried out under visual control.

Then it is possible to clearly designate all possible directions of movement using words (relative to body parts). Coordination in physical education is also agility, which is the ability to quickly remake motor activity in a changing unexpected environment. In such activities, there are special requirements for the ability to concentrate and attention; sufficient reaction speed is required.

Coordination in physical education is a set of warm-up exercises.

Of the general exercises, the following workouts are most useful for agility:

- Quick change of position. For example, from a supine position, you need to sit down and straighten your legs, then bend your right leg at the knee, then your left; then stretch your legs again and lie down in the starting position.

- Requires coordinated action of three or more people. For example, transferring an object in a column.

- Game sports have an undoubted advantage in this regard.

The development of coordination skills and abilities also involves working on balance. It is more difficult the less space there is for support. Equilibrium always correlates with inertia from the previous movement, since subsequently there is an instantaneous transition to statics. For example, when performing a certain number of rotations, it is difficult to remain in balance, and even more difficult to remain motionless at the end.

Exercises that are useful for balance:

- Rotates 360 degrees in one direction and the other.

- Raising on your toes when your feet are placed together. Squats on your toes with a straight back are also effective.

- One leg is fixed in place and serves as a support, and the second is moved forward, to the side, and back. Perform the exercise one by one.

- Raising one leg, leaning on the other one. Then repeat with your eyes closed. In conclusion, you need to stay for 3-4 seconds. on one supporting leg.

Causes of impaired coordination of movements

There are many reasons for impaired movement coordination. These include the following factors:

- physical exhaustion of the body;

- exposure to alcohol, narcotic and other toxic substances;

- brain injuries;

- sclerotic changes;

- muscle dystrophy;

- ;

- ;

- catalepsy is a rare phenomenon in which the muscles weaken due to an explosion of emotions, say, anger or delight.

Lack of coordination is considered a dangerous deviation for a person, because in such a state it costs nothing to get injured. This often accompanies old age, as well as previous neurological diseases, a striking example of which in this case is stroke. Impaired coordination of movements also occurs in diseases of the musculoskeletal system (poor muscle coordination, weakness in the muscles of the lower extremities, etc.) If you look at such a patient, it becomes noticeable that it is difficult for him to maintain an upright position and walk.

People with such ailments move uncertainly, their movements show laxity, too much amplitude, and inconsistency. Having tried to outline an imaginary circle in the air, a person is faced with a problem - instead of a circle, he gets a broken line, a zigzag. Another test for incoordination is to ask the patient to touch the tip of the nose, which also fails. Looking at the patient’s handwriting, you will also be convinced that his muscle control is not all right, since letters and lines creep on top of each other, becoming uneven and sloppy.

Basic indicator of coordination

You should understand what indicators measure coordination:

- movement accuracy;

- variety and complexity of movement;

- time;

- accuracy of response to an object in motion;

- rhythm;

- ability to maintain balance;

- ability for spatial orientation;

- rationality of action (expediency and economy);

- accuracy.

These indicators are practiced in physical education classes. However, the main and most comprehensive indicator in assessing coordination should be considered the ability to quickly rearrange the entire motor program. To analyze individual coordination abilities, it is necessary to observe a person for 2-3 years.

It is possible to predict the prognosis for the development of coordination in the future from childhood. A favorable time for predicting the development of coordination in the category “bodily agility” (gymnastics) is 6-7 years. Category “subject dexterity” (sports games) 11-12 years old.

Definition of the concept[edit | edit code]

Intermuscular coordination[edit | edit code]

Rice.

1. Muscle activity (electromyography) in an untrained person (left) and in a trained swimmer during freestyle swimming (right). Intermuscular coordination refers to the interaction of the muscles involved in the movement (Weineck, 2007). It is based on the contraction of the corresponding muscles (agonists and synergists) in an optimal order and with optimal intensity. Movement is controlled by the central nervous system (CNS) - while sending signals to effectors (muscles or muscle groups performing the movement), it simultaneously activates synergists and inhibits antagonists.

Remember

: Coordination in sports refers to various phenomena: intra- and intermuscular coordination, as well as the so-called coordination abilities, or motor coordination. When interpreting these concepts, it often remains unclear to what extent they are synonymous, in what sense they overlap or, conversely, are used interchangeably without any reason. It is also often unclear how different forms of coordination should be trained and whether it is appropriate to distinguish, for example, between training aimed at developing general fitness (say, strength) and training for coordination or coordination skills, as presented in many sports training models.

In Fig. Figure 1 shows the activity of the muscles involved in crawl swimming, determined using electromyography (EMG). The left side shows the electromyogram of the muscles of beginner athletes, the right side shows experienced athletes. A comparison of the so-called On-Set and Off-Set moments, i.e. the beginning and cessation of muscle activity, as well as the height of the EMG amplitude show that in an experienced athlete the muscles act more coordinated than in a beginner. This is especially evident when comparing the activity of the deltoid, latissimus dorsi and trapezius muscles. Similar to the coordinated work of muscles, the phases of activity of agonists and antagonists in beginning athletes overlap over a wider time interval; this phenomenon is called coordination of the activity of antagonist muscles. Thus, for beginners, the agonist must not only cope with the weight of one or another part of the body, moving it and overcoming the force of gravity, but also additionally resist the activity of the antagonist. While in the early stages of training it is not uncommon for extensors and flexors to be activated simultaneously and thus inhibit each other, in later stages of training muscle contraction often occurs sequentially and alternately: first one type of muscle contracts, and then the other ( Schollhorn, 2003). Studying the counteraction of antagonistic muscles leads to an alternative approach to coordination. If we consider the mechanical control of movement from the point of view of the fact that muscles and muscle groups contract at the right moment with the appropriate intensity, then it should be added as a necessary condition that the antagonists of such muscles must relax at the right moment (Schollhorn, 2003). This approach to intermuscular coordination and its training, however, represents not only an understanding of this topic from the opposite point of view, but also allows us to offer some additional types of training. For example, if during running or sprint training, due to an increase in the lifting of the knee upward, the athlete’s step length increases, then in addition to strengthening the hip flexor muscles (agonists), movement coordination also improves. This is because by relaxing the hip extensors (antagonists) at the right moment, it is possible to minimize the resistance of the hip flexors.

Intramuscular coordination[edit | edit code]

Rice.

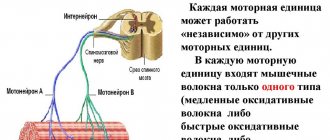

2. The principle of increasing according to Henneman. First, smaller motor units are recruited, then larger ones: ME - motor unit If intermuscular coordination refers to the interaction of agonists, synergists and antagonists, visible to the naked eye, i.e., occurring at the macro level, then in the case of intramuscular coordination we are talking about processes observed at the microscopic level. Weineck (2007) believes that the concept of intramuscular coordination refers to increased responsiveness to nerve impulses, namely the activation of more motor units. Of particular importance in this case is the synchronicity of their activation. From the point of view of the incremental principle (Henneman, Olson, 1965; Henneman et al 1974), the development of strength is associated with the sequential innervation of additional motor units, i.e., gradually, at an increasingly higher frequency of stimulation, larger and stronger units are recruited (Fig. 2 ).

Due to the sequential recruitment of motor units, the force reaches similar values later than with their synchronous activation.

rice. 3. Graph of development of maximum strength and processes of neural (neuromuscular) and muscular (hypertrophy) adaptation during strength training

Improved intramuscular coordination, together with improved intermuscular response, represents the first response of a muscle or neuromuscular system to repeated stimulation. This is observed with different patterns of development of maximum strength and an increase in the cross-sectional area of the working muscle at the very initial stage of strength training. While increases in maximum strength usually occur over a short period of time, increases in the cross-sectional area of the working muscle become noticeable only after several weeks (Friedebold et al. 1957). In Fig. 3. A graph of these processes is presented.

The increase in maximum strength on the graph is explained by improved inter- and intramuscular coordination. Based on the results of the study by Fukunaga (1976), it is possible to present the processes of strength development and increase in muscle cross-sectional area, as well as electromyographic activity, in more detail (Fig. 4).

During the first phase of training, strength and electromyographic activity increase, but the cross-sectional area of the muscle does not increase. A simultaneous increase in electromyographic activity is an indicator of the activation of a larger number of motor units, which is confirmed, in turn, by a more intense development of force (Coburn et al., 2004; Komi, 1986). The growth of strength at the very beginning is thus associated not so much with muscular-physiological processes of adaptation, but with neuromuscular adaptation, which is why Fukunaga (1976) assigns an important role to training issues. Only after the intramuscular reserves of the body and the power capabilities of the muscle are exhausted does it begin to react: the cross-sectional area of individual motor units increases, resulting in an increase in the cross-sectional area of the muscle as a whole {see. rice. 4). [[Image:|250px|thumb|right|Fig. 4. Scheme of the processes of development of muscle strength, increase in muscle cross-sectional area and changes in electromyographic activity during a certain period of training]] A study by Moritani and de Vries (1979) examined the relationship between motor unit innervation and the size of muscle cross-sectional area. During 12 weeks of strength training of the elbow flexor muscles in only one arm, increased electromyographic activity, increased strength, and increased muscle cross-sectional area were observed. In the second arm, only manifestations of neuromuscular adaptation were observed in the form of increased electromyographic activity and increased strength. In the second half of this training phase, a decrease in electromyographic activity was observed, which was caused by an increase in the cross-sectional area of the muscle of the trained arm due to hypertrophy. This is explained by the fact that individual motor units, with an increase in their cross-sectional area, can develop more force, so that to maintain a constant force, it is enough to activate a small number of them. In the untrained arm, there was no decrease in electromyographic activity due to the lack of increase in muscle cross-sectional area. Hypertrophy of a muscle and training aimed at it thus only increases the possible strength potential of the muscle. In order to fully implement it, additional training is prescribed to improve intramuscular coordination. For strength training, the sequence of adaptation processes plays a significant role (inter- and intramuscular optimization precedes an increase in the cross-sectional area of the muscles), since an increase in strength can occur without a simultaneous increase in mass in the form of “thickening” of the muscle. This improves relative strength (Letzelter, 1978) and reduces the muscle need for additional nutrients. Regarding relative strength, this aspect can play a big role if you need to increase the speed of your own body. Reduced muscle demand for additional nutrients may be the reason that the body first optimizes the processes occurring in the muscles and their interaction, and only then begins to look for an unfavorable solution from an energy point of view and increase muscle mass. Current research questions the extent to which already improved neural activation can cause hypertrophy. This point of view is clarified by studies of age-related atrophy, which show that the cause of muscle loss is a weakening of neuromuscular activation (Saini et al., 2009; Narici, Maganaris, 2006; Boonyarom, Inui, 2006). It follows that training of intramuscular activity must take into account certain requirements: if it is necessary to achieve synchronous voluntary activation of the largest number of motor units in the shortest possible time, the training must include appropriate stimuli - usually in the range from submaximal to maximum stimuli within a minimally short period of time.

Coordination abilities[edit | edit code]

Main article:

Coordination abilities

In addition to inter- and intramuscular coordination, the concept of “coordination” is mentioned in sports scientific research, which implies the so-called coordination abilities: “Coordination is a collective term that describes a number of coordination abilities” (Hohmann et al., 2007). By these abilities we mean a certain theoretical concept that allows us to reduce all kinds of sports movements to a certain number of constant factors. Attempts to isolate these constant factors from the entire variety of human motor skills were first made by Fleischmann (1953,1956). Using factor analysis techniques, which conducted extensive tests on hundreds of participants (mostly Air Force personnel), the various psychomotor and physical abilities underlying the total motor performance studied were identified (Summers, 2004). In German-speaking countries, the concept of coordination abilities is primarily based on Hirtz's (1985) concept of abilities, which includes the following five coordination abilities:

- ability to respond;

- rhythmic ability;

- ability to balance;

- ability for spatial orientation;

- ability for kinesthetic differentiation;

and additionally introduced by the scientist Blume (1978,1981):

- ability for intermuscular coordination;

- ability to restructure the motor program.

As with other trends in sport science that have become somewhat independent (e.g. training principles, Schollhorn et al, 2005), when considering coordination abilities, it also becomes apparent that this is a conventional model, the original application of which was to determine the basis of motor functions. quite justifiably, it was later often transferred to practice thoughtlessly and uncritically (Hohmann et al, 2007). Thus, the concept, aimed at developing fundamental sports principles of a general nature, over time turned into an imaginary requirement for all other types of movement in sports. In practice, this leads to the fact that during the preparatory phase in some sports, “general coordination abilities” are first trained, and then they move on to training indicators associated with a particular sport. In this case, a so-called vicious circle or paralogism arises (Mittelstrass, 2004). Numerous experimental data indicate that it is unlikely that there are any coordination abilities independent of the sport; we can talk about coordination characteristics specific to certain tasks and situations that are associated with the characteristics of various sports. If coordination abilities—such as balance—existed as permanent behavioral characteristics (Hohmann et al. 2007), then athletes participating in sports in which balance is a fundamental requirement should have no difficulty pass any balance test. Balance tests in which such athletes (including surfing and cross-country skiing) and athletes involved in sports that do not require highly developed balance abilities (including tennis, football, track and field) participated, although they showed better results the first in comparison with the second, however, the results of the first also differed significantly from each other. The closer the test was to reproducing typical conditions for a given sport, the better the athletes' performance was (Busch et al., 2003; Teipel, 1995). Such test results, however, are not consistent with the assumption that the corresponding abilities are constantly present, that is, regardless of the situation. Also, the results of experiments speak against the general nature of the concept of coordination abilities: it is impossible to completely “transfer” coordination indicators characteristic of playing one sport or obtained under certain conditions to other situations (Hohmann et al., 2007). The concept of coordination abilities in elite sports was considered insufficiently differentiated in early works, which led to the development of a taxonomy for the study of various sports based on the specifics of each of them.

Thus, the concept of coordination abilities does not have much evidence base. Rather, the concept is—and its original purpose—a practical guide to the development of fundamental motor functions in childhood with the goal of subsequent comprehensive motor development (Hirtz, 1985; Hohmann et al., 2007). In the process of sports training, the connection between the above-mentioned abilities and the specifics of a particular sport is clearly demonstrated, which, in turn, raises the question of how to distinguish coordination training from training aimed at improving technique. This issue will be discussed in the next section of the book. At the same time, proposals for organizing coordination training are considered as part of the theory of differentiated learning (Schollhorn, 1999).

Methods for developing coordination

Coordination in physical education is capabilities that represent readiness for optimal regulation of movement.

Methods for developing coordination include:

- variable exercise;

- a game;

- competition.

In physical education classes, game techniques are the most effective for working on coordination. The competitive spirit encourages you to exert great effort to achieve your goal. The most effective way is collective sports games. They help to develop the proportionality and clarity of the movements performed. During such activities, skills of rapid movements under changing circumstances are formed.

It is also important to conduct relay races, since they are organized within a certain time frame. Such activities using basketballs are especially effective.

Work on the vestibular apparatus is an extremely significant factor for overall development, as well as improving the ability to navigate in space. It provides a basis for learning new spatial movement skills.

The main methods for studying coordination abilities: testing and observation. Achievement in coordination is typically assessed using age- and health-related tests.

A set of coordination exercises

To train coordination, there are many exercises and entire complexes designed for training various groups.

The simplest complex for working with teenagers and groups of pensioners may be the following:

| A set of exercises to improve coordination abilities | |||

| № | Exercise | Dose | Recommendations |

| 1 | Ball toss | 5-6 min. | — |

| 2 | A few steps, somersault forward | 4 times | — |

| 3 | Throwing a ball at a target | 15 times | Each time increase the distance to the designated goal. |

| 4 | Jumping with a turn | 3 min. | 180° or 360° |

Types of coordination

Coordination is an innate ability. It, like everyone else, needs to be developed and improved. It synchronizes movements; with poorly developed coordination, it will be difficult to lead a normal life. It should be noted that this human ability deteriorates more than others when aging.

Without coordination, muscle movement is impossible. It is developed in almost every sport. Innate natural ability can be improved at every age.

Coordination happens:

- Intermuscular: the relationship of the muscles involved in the movement (intensity and order of muscle contractions).

- Intramuscular: muscles and their nerve impulses.

Symptoms of impaired coordination of movements

The following symptoms of impaired coordination of movements exist:

- Unsteady movements - This symptom occurs when the muscles of the body, especially the limbs, weaken. The patient's movements become uncoordinated. When walking, he sways a lot, his steps become abrupt and have different lengths.

- Tremor - shaking of the hands or head. There is a strong and almost imperceptible tremor. In some patients it begins only during movement, in others - only when they are motionless. With severe anxiety, the tremor increases; shaky, uneven movements. When the muscles of the body are weakened, the limbs do not receive a sufficient basis for movement. The patient walks unevenly, intermittently, the steps are of different lengths, and he staggers.

- Ataxia is caused by damage to the frontal parts of the brain, cerebellum, and nerve fibers transmitting signals through the channels of the spinal cord and brain. Doctors distinguish between static and dynamic ataxia. With static ataxia, a person cannot maintain balance in a standing position; with dynamic ataxia, it is difficult for him to move in a balanced manner.

Factors influencing coordination of movements

Motor functions require many qualities that are acquired through training. By doing the exercises day after day, a level of skill is achieved, speed and strength increase.

Factors on which coordination depends:

- adequate motion analysis;

- difficulty in motor exercises;

- level of other physical capabilities;

- bravery;

- age;

- general preparedness and more.

Coordination also includes a sense of time, a perception of space where there is rhythm and a certain tempo that can change. It is based, in turn, on the ability to maintain attention, focus, and concentrate. Developed coordination requires intelligence, resourcefulness, and composure.

Recommendations for developing coordination

Development of coordination is carried out in the following directions:

- Performing different exercises, where there is a novelty in their reproduction from lesson to lesson.

- Increasing the complexity of assigned tasks, working on accuracy.

- Development of balance.

- Vestibular function training.

Methodological recommendations: quick change of positions (stand up, sit down); originality and unexpectedness of the position (running from a sitting position); change in speed with change in sequence order; using objects of different weights and volumes in training.

Practical tips:

- When working with young children, you should start with static exercises that simultaneously develop spatial orientation, balance and visual assessment of your own actions.

- A systematic approach to the frequency of training, since with long breaks there is a decrease in motor activity.

- When organizing classes, diversify the set of exercises and games as much as possible.

- Creating the most friendly environment in the group.

Game for developing running “Catch-up”

Goal: learning to navigate in space, developing short-distance running skills, training the ability to quickly execute simple commands during the game.

Format: group.

Progress of the game: One child sits on a chair, an adult approaches him with other children, they say:

We are funny guys

We love to run and play!

Well, try to catch up with us,

One two three four five!

At the word “Five,” everyone runs, and the child sitting on the chair gets up and catches up. The one he caught sits on a chair and the game repeats.

Coordination Development Tools

The main means of training coordination are novelty and difficulty of execution. Difficulty increases by, for example, reducing time, increasing distances, making objects heavier, and so on. Coordination activities cease to be effective when their implementation becomes automatic. Then their value disappears, as each, studied in full and done under the same conditions, does not contribute to development.

In addition, other motor skills besides coordination need to be worked on. The coordination ability of an individual plays a significant role in regulating movements. It promotes coordination and control of various motor activities depending on the assigned tasks.

A person needs to interact with the external environment, it is necessary to predict its possible transformations, to anticipate future events; and based on this, create your own model of action focused on achieving your goals.

Improving motor functions is the main goal of physical education. This task naturally implies the development of coordination in all its forms. First of all, training is necessary for children and older people. Work with other groups in this regard depends on the professional orientation of the latter.

Components of Coordinated Movement

Coordinated movements depend on:

- Willpower: the ability to initiate, maintain, or stop an action or movement.

- Perception: interaction between the proprioceptive system and subcortical centers to integrate motor impulses and produce sensory response. When proprioception is impaired, it is partially compensated by visual feedback.

- Engram: A physical or biochemical change in nervous tissue that represents the memory of experienced states. The study proved that a high number of repetitions must be performed in order for an engram to form. According to a 1980 study: “It takes thousands of repetitions to begin to form an engram and millions of repetitions to perfect it. Coordination develops in proportion to the number of repetitions practiced just below the maximum level of ability to perform.”