Synonyms:

- encephalopathy,

- chronic cerebral ischemia,

- slowly progressive cerebrovascular accident,

- chronic ischemic brain disease,

- cerebrovascular insufficiency,

- vascular encephalopathy,

- atherosclerotic encephalopathy,

- hypertensive encephalopathy,

- atherosclerotic angioencephalopathy,

- vascular (atherosclerotic) parkinsonism,

- vascular (late) epilepsy,

- vascular dementia.

The most widely used term in domestic neurological practice is “dyscirculatory encephalopathy ,” which retains its meaning to this day.

Causes of chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency:

Basic:

- atherosclerosis;

- arterial hypertension.

Additional:

- heart disease with signs of chronic circulatory failure;

- heart rhythm disturbances;

- vascular abnormalities, hereditary angiopathy;

- venous pathology;

- vascular compression;

- arterial hypotension;

- cerebral amyloidosis;

- diabetes;

- vasculitis;

- blood diseases.

For adequate brain function, a high level of blood supply is required. The brain, whose mass is 2.0-2.5% of body weight, consumes 20% of the blood circulating in the body. The value of cerebral blood flow in the hemispheres is 50 ml per 100 grams per minute, glucose consumption is 30 µmol per 100 grams per minute, and in gray matter these values are 3-4 times higher than in white matter. Under resting conditions, the brain's oxygen consumption is 4 ml per 100 grams per minute, which corresponds to 20% of the total oxygen entering the body. With age and in the presence of pathological changes, the amount of cerebral blood flow decreases, which plays a decisive role in the development and increase of chronic cerebral circulatory failure.

The presence of headaches, dizziness, memory loss, sleep disturbances, the appearance of noise in the head, ringing in the ears, blurred vision, general weakness, increased fatigue, decreased performance and emotional lability - these symptoms most often simply “inform” a person about fatigue. Only when the vascular genesis of the “asthenic syndrome” is confirmed and focal neurological symptoms are identified, a diagnosis of “dyscirculatory encephalopathy” is made.

The basis of the clinical picture of discirculatory encephalopathy is currently recognized as cognitive impairment . In case of chronic cerebrovascular accident, it should be noted that there is an inverse relationship between the presence of complaints, especially those reflecting the ability to cognitive activity (memory, attention), and the severity of chronic failure: the more cognitive functions suffer, the fewer complaints. In parallel, emotional disorders develop (emotional lability, inertia, lack of emotional response, loss of interests), various “motor disorders” (disorders of walking and balance).

V.V. Zakharov Department of Nervous Diseases MMA named after. THEM. Sechenov, Moscow

One of the most common pathological conditions in neurological practice is brain damage of vascular etiology, which includes stroke and chronic insufficiency of blood supply to the brain. According to the World Federation of Neurological Societies, at least 15 million strokes are registered annually in the world. It is also assumed that a significant number of acute cerebrovascular accidents remain unaccounted for. Stroke is in third place among the causes of mortality and in first place among the causes of disability, which emphasizes the high relevance of this problem both for medical workers and for society as a whole [10]. The existence of chronic cerebral ischemia has long been disputed in foreign literature. Leading world angioneurologists, such as V. Khachinsky and others, in 1970-1980. postulated that there cannot be structural damage to the brain without stroke [15]. However, the development of modern neuroimaging methods has shown that long-term uncontrolled arterial hypertension can lead to diffuse changes in the deep parts of the white matter of the brain (the so-called leukoaraiosis), which is currently considered as a neuroimaging correlate of chronic cerebral ischemia [7, 20]. Stroke and chronic cerebral ischemia are caused by common causes, the most common of which are cerebral artery atherosclerosis and arterial hypertension. Due to the etiological commonality, both pathological processes are usually present simultaneously: patients with chronic insufficiency of blood supply to the brain have anamnestic or neuroimaging signs of strokes, and patients with stroke have signs of chronic cerebral ischemia. Assessing the contribution of each pathogenetic mechanism separately to the formation of clinical symptoms seems very difficult, and from a practical point of view, impractical. Therefore, at present, discirculatory encephalopathy (DE) is generally understood as a clinical syndrome of brain damage of vascular etiology, which can be based on both repeated strokes and chronic insufficiency of blood supply to the brain or a combination of both [3, 5]. Some other terms are also proposed to denote this clinical condition, such as chronic cerebral ischemia, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic cerebral disease, etc. However, from our point of view, the term “dyscirculatory” encephalopathy is the most appropriate, since it reflects the localization of the lesion, its nature and at the same time is not strictly connected with a specific pathogenetic mechanism: only with acute or only with chronic cerebral ischemia.

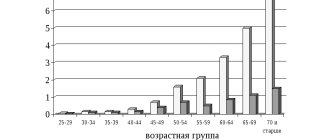

Clinical manifestations of discirculatory encephalopathy Clinical manifestations of DE can be very diverse. As mentioned above, most patients with chronic vascular diseases of the brain have a history of strokes, often more than once. The localization of strokes undoubtedly largely determines the characteristics of the clinic. However, in most cases of cerebrovascular pathology, along with the consequences of strokes, there are also neurological, emotional and cognitive symptoms of dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain. This symptomatology develops as a result of disruption of connections between the frontal cortex and the subcortical basal ganglia (the “disconnection” phenomenon). The cause of “disconnection” is diffuse changes in the white matter of the brain, which, as mentioned above, are a consequence of arterial hypertension [3, 17]. Depending on the severity of the disorders, it is customary to distinguish three stages of DE. At stage I, symptoms are predominantly subjective. Patients complain of headache, unsystematic dizziness, tinnitus or heaviness in the head, sleep disturbance, increased fatigue during physical and mental stress, forgetfulness, and difficulty concentrating. Obviously, the above symptoms are nonspecific. It is assumed that they are based on a slight or moderate decrease in mood. Emotional disorders in chronic insufficiency of blood supply to the brain are of an organic nature and are the result of secondary dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain due to disruption of frontostriatal connections [3]. Along with emotional disorders, at stage I of DE, impairments of cognitive functions can also be detected, most often in the form of slowness of higher nervous activity, a decrease in the volume of RAM, and inertia of intellectual processes. These neuropsychological symptoms reflect involvement of the deep parts of the brain with secondary dysfunction of the frontal lobes. As a rule, at stage I DE, cognitive impairment does not form a clinically defined syndrome and is therefore classified as mild [3, 8, 9]. In the neurological status, there may be an increase in tendon reflexes, often asymmetrical, uncertainty when performing coordination tests, and slight changes in gait. Like emotional and cognitive disorders, changes in the neurological status at this stage of DE are nonspecific, therefore, instrumental research methods confirming the vascular nature of brain damage are of fundamental importance for diagnosing cerebrovascular insufficiency at stage I DE [3, 5]. Stage II of discirculatory encephalopathy is spoken of in cases where neurological or mental disorders form a clinically defined syndrome. For example, we may be talking about mild cognitive impairment syndrome. Such a diagnosis is legitimate in cases where impairments in memory and other cognitive functions clearly go beyond the age norm, but do not reach the severity of dementia [8, 19, 21]. At the same time, in the structure of cognitive disorders, neuropsychological symptoms of frontal-subcortical dysfunction usually retain their dominant position. At stage II of DE, pseudobulbar syndrome, extrapyramidal disorders in the form of hypokinesia, mild or moderate increase in muscle tone of the plastic type, ataxic syndrome and other objective neurological disorders can also develop. On the other hand, subjective neurological disorders characteristic of stage I DE usually become less pronounced or less relevant for patients [3, 5]. At stage III of dyscirculatory encephalopathy, there is a combination of several neurological syndromes and, as a rule, vascular dementia is present - impairments of memory and other cognitive functions of vascular etiology, which lead to maladjustment of the patient in everyday life. Vascular dementia is one of the most severe complications of cerebrovascular insufficiency. According to statistics, vascular dementia is the second most common cause of dementia in old age after Alzheimer's disease and is responsible for at least 10-15% of dementias. As a rule, vascular dementia is accompanied by severe gait disturbances, in the pathogenesis of which dysfunction of the frontal regions of the brain also plays a role. Pseudobulbar syndrome, pelvic disorders, etc. are also very characteristic [4]. Vascular dementia, like DE in general, is a pathogenetically heterogeneous condition. Vascular dementia can occur as a result of a single stroke in a strategic area of the brain for cognitive activity or as a result of repeated strokes in combination with chronic cerebral ischemia. In addition, in addition to cerebral ischemia and hypoxia, secondary neurodegenerative changes play an important role in the pathogenesis of dementia in cerebrovascular insufficiency, at least in some patients with DE. Modern research convincingly shows that insufficient blood supply to the brain is a significant risk factor for the development of degenerative diseases of the central nervous system, in particular Alzheimer's disease (AD). The addition of secondary neurodegenerative changes undoubtedly aggravates and modifies cognitive disorders in cerebrovascular insufficiency. At the same time, memory impairments become more pronounced, which initially extend to current events, and as the disease progresses, to more distant life events. In such cases, the diagnosis of mixed (vascular-degenerative) dementia is legitimate [4].

Diagnosis of DE To diagnose dyscirculatory encephalopathy syndrome, a thorough study of the disease history, assessment of the neurological status, and the use of neuropsychological and instrumental research methods are necessary. It is important to emphasize that the presence of cardiovascular diseases in an elderly person does not in itself prove the vascular nature of the detected neurological disorders. Evidence is needed of a cause-and-effect relationship between the symptoms observed in the clinical picture and vascular damage to the brain, which is reflected in the diagnostic criteria of DE accepted today: (according to Yakhno N.N., Damulin I.V., 2001): • presence of signs (clinical , anamnestic, instrumental) brain damage; • presence of signs of acute or chronic cerebral dyscirculation (clinical, anamnestic, instrumental); • the presence of a cause-and-effect relationship between hemodynamic disorders and the development of clinical, neuropsychological, and psychiatric symptoms; • clinical and paraclinical signs of progression of cerebrovascular insufficiency. Arguments in favor of such a connection may be the presence of focal neurological symptoms, a history of stroke, characteristic changes in neuroimaging, such as post-ischemic cysts or pronounced changes in white matter, the specific nature of cognitive impairment in the form of a predominance of symptoms of frontal-subcortical dysfunction over memory impairment.

Treatment of DE Cerebrovascular insufficiency is a complication of various cardiovascular diseases, therefore etiotropic and pathogenetic therapy of DE should be primarily aimed at the underlying pathological processes of chronic cerebral vascular insufficiency, such as arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis of the main arteries of the head, heart disease and etc. Adequate antihypertensive therapy is one of the most important measures in the management of patients with cerebrovascular insufficiency. Arterial hypertension is one of the most powerful and independent risk factors for acute cerebrovascular accidents. Long-term uncontrolled arterial hypertension leads to secondary changes in the vascular wall of small-caliber arteries (arteriolosclerosis), which underlies chronic ischemia of the deep parts of the brain. In addition, it has now been proven that arterial hypertension is also a risk factor for the neurodegenerative process, which often complicates the course of vascular dementia. Therefore, adequate antihypertensive therapy is an essential factor in the secondary prevention of the increase in mental and motor symptoms of DE. One should strive for complete normalization of blood pressure (target figures are no more than 140/80 mm Hg), which, according to international studies, significantly reduces the risk of both acute cerebrovascular accidents and vascular and primary degenerative dementia. However, normalization of blood pressure should be done slowly, over several months. A rapid decrease in blood pressure can lead to worsening cerebral perfusion due to improper reactivity of arterioles altered by lipohyalinosis [13, 16, 23]. The presence of atherosclerotic stenosis of the main arteries of the head requires the prescription of antiplatelet agents in cases where the stenosis exceeds 70% of the vessel lumen or the integrity of the vascular wall is compromised. Drugs with proven antiplatelet activity include acetylsalicylic acid in doses of 50-100 mg per day and clopidogrel (Plavix) in a dose of 75 mg per day. Studies have shown that the use of these drugs reduces the risk of ischemic events (myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, peripheral thrombosis) by 20-25%. However, it should be kept in mind that there are individual differences in response to antiplatelet agents. In some cases, the effectiveness of these drugs is insufficient, and in some patients a paradoxical proaggregant effect is observed. Therefore, after prescribing acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel, a laboratory study of the aggregation of blood cells is necessary [2]. In order to enhance the antiplatelet effect of acetylsalicylic acid, it may be advisable to simultaneously administer dipyridamole at a dose of 25 mg three times a day. Monotherapy with this drug did not show any preventive effect against cerebral or other ischemia, however, when used in combination, dipyridamole significantly increases the preventive effect of acetylsalicylic acid [2]. In addition to prescribing antiplatelet agents, the presence of atherosclerotic stenosis of the main arteries of the head requires consultation of the patient with vascular surgeons to decide on the advisability of surgical intervention. Currently, the positive preventive effect of surgery in patients with a history of transient ischemic attacks or small strokes has been proven. The benefits of surgery for asymptomatic stenosis are less convincing [2]. If there is a high risk of cerebral thromboembolism, for example with atrial fibrillation and valvular disease, antiplatelet agents may be ineffective. The listed conditions are an indication for the prescription of indirect anticoagulants; the drug of choice is warfarin. Therapy with indirect anticoagulants should be carried out under strict monitoring of coagulation parameters, and the international normalized ratio (INR) should be examined every two weeks [2]. The presence of hyperlipidemia that cannot be corrected by diet requires the prescription of lipid-lowering drugs. The most promising in this case are statins (Zocor, Simvor, Simgal, Rovacor, Medostatin, Mevacor, etc.). Currently, the prescription of these drugs is considered justified not only for hyperlipidemia, but also for normal cholesterol levels in patients with coronary heart disease or diabetes mellitus. The advisability of prescribing these drugs to prevent the development of cognitive impairment and dementia is also discussed, which, however, requires further research [6, 11, 18]. An important pathogenetic event is also the impact on other known risk factors for cerebral ischemia, which include smoking, diabetes mellitus, obesity, physical inactivity, etc. [4, 11, 18]. In the presence of cerebrovascular insufficiency, it is pathogenetically justified to prescribe drugs that act primarily on the microvasculature, such as: • phosphodiesterase inhibitors: aminophylline, pentoxifylline, vinpocetine, tanakan, etc. The vasodilating effect of these drugs is associated with an increase in the content of cAMP in the smooth muscle cells of the vascular wall, which leads to to their relaxation and increase in the lumen of blood vessels [5, 6]; • calcium channel blockers: cinnarizine, flunarizine, nimodipine. They have a vasodilating effect due to a decrease in the intracellular calcium content in the smooth muscle cells of the vascular wall. Clinical experience suggests that calcium channel blockers, such as cinnarizine and flunarizine, may be more effective for circulatory failure in the vertebrobasilar system [1, 5, 6]; • a2-adrenergic receptor blockers: nicergoline. This drug eliminates the vasoconstrictor effect of the mediators of the sympathetic nervous system: adrenaline and norepinephrine [5, 6]. In neurological practice, vasoactive drugs are most often prescribed. In addition to their vasodilatory effects, many of them also have positive metabolic effects, which allows them to also be used as symptomatic nootropic therapy. In domestic neurological practice, vasoactive drugs are usually prescribed in courses of two to three months, once or twice a year [5, 6]. Metabolic therapy is widely used for cerebrovascular insufficiency, the purpose of which is to increase the compensatory capabilities of the brain associated with the phenomenon of neuronal plasticity. Neuronal plasticity is understood as the ability of neurons to change their functional properties during life, namely to increase the number of dendrites, form new synapses, and change membrane potential. It is likely that neuronal plasticity underlies the process of restoration of lost functions that is observed after a mild stroke or other brain damage. Metabolic drugs include pyrrodoline derivatives (piracetam, pramiracetam, phenotropil), which have a stimulating effect on metabolic processes in neurons. The experiment found that the use of piracetam increases intracellular protein synthesis and utilization of glucose and oxygen. With the use of this drug, there is also an increase in blood supply to the brain, which is likely secondary to an increase in metabolic processes. In clinical practice, the positive effect of piracetam has been shown in patients with mild cognitive impairment of an age-related nature, in the recovery period of ischemic stroke, especially in cortical lesions with clinical aphasia, as well as in mental retardation in childhood [5, 6]. Another strategy for influencing cerebral metabolism is the use of peptidergic and amino acid drugs. These include Cerebrolysin, Actovegin, glycine and some others. They contain biologically active compounds that have multimodal beneficial effects on neurons. Clinical and experimental studies of peptidergic drugs indicate an increase in the survival of neurons in various pathological conditions, improvement of cognitive functions, and regression of other neurological disorders [5, 6]. Like vasoactive drugs, metabolic therapy is traditionally given in courses once or twice a year. Pathogenetically justified and appropriate is the combined implementation of vasoactive and metabolic therapy. Currently, the doctor has several combined dosage forms at his disposal, which include active substances with vasoactive and metabolic effects. These drugs include instenon, vinpotropil, Phezam and some others. Phezam is a combined vascular-metabolic drug that contains 25 mg of cinnarizine and 400 mg of piracetam. As mentioned above, cinnarizine is a calcium channel blocker, which has the greatest effect on microcirculation in the vertebrobasilar region. Therefore, the use of Phezam has the most beneficial effect on symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency, such as vestibular disorders, dizziness and unsteadiness when walking. It should be noted that in addition to vasoactive properties, cinnarizine also has a symptomatic effect against systemic dizziness, so Phezam can be used not only for cerebrovascular insufficiency, but also for symptomatic purposes in peripheral vestibulopathy. Piracetam, which is part of the drug, effectively promotes the normalization of cognitive functions and memory, the reduction of residual effects of a neurological defect, psychopathological and depressive symptoms, the elimination of disorders of autonomic regulation, asthenia, insomnia, and the improvement of general well-being and performance. Fezam is prescribed one or two capsules three times a day for two to three months. Contraindications to the use of Phezam are severe impairment of liver and/or kidney function, parkinsonism, pregnancy and lactation, and children under five years of age. The development of vascular dementia syndrome requires more intensive nootropic therapy. Of the modern nootropic drugs, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have the most powerful clinical effect on cognitive functions. These drugs were initially used to treat mild to moderate dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. However, today their clinical effectiveness has also been proven in vascular and mixed dementia [11, 12, 14, 18, 22]. In conclusion, it should be emphasized that a comprehensive assessment of the state of the cardiovascular system of patients with cerebrovascular insufficiency, the impact on both the cause of the disorders and the main symptoms of DE, undoubtedly helps improve the quality of life of patients and prevent severe complications of cerebrovascular insufficiency, such as vascular dementia and movement disorders.

Literature 1. Andreev N.A., Moiseev V.S. Calcium antagonists in clinical medicine. M.: RC "Pharmedinfo", 1995. 161 p. 2. Warlow C.P., Dennis M.S., J. van Geyn et al. Stroke. Practical guide for the management of patients / trans. from English St. Petersburg, 1998. P. 629. 3. Damulin I.V. Dyscirculatory encephalopathy in the elderly and senile age / Abstract of thesis... Dr. med. M., 1997. 32 p. 4. Damulin I.V. Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia / ed. N.N. Yakhno. M., 2002. P. 85. 5. Damulin I.V., Parfenov V.A., Skoromets A.A., Yakhno N.N. Circulatory disorders in the brain and spinal cord // Diseases of the nervous system. Guide for doctors / ed. N.N. Yakhno, D.R. Shtulman. M., 2003. pp. 231-302. 6. Zakharov V.V., Yakhno N.N. Memory impairment. M.: GeotarMed, 2003. P. 150. 7. Martynov A.I., Shmyrev V.I., Ostroumova O.D. et al. Features of damage to the white matter of the brain in elderly patients with arterial hypertension // Clinical Medicine. 2000. No. 6. P. 11-15. 8. Yakhno N.N., Zakharov V.V., Lokshina A.B. Syndrome of moderate cognitive impairment in dyscirculatory encephalopathy // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry named after. S.S. Korsakov. 2005. T. 105. No. 2. P. 13-17. 9. Yakhno N.N., Lokshina A.B., Zakharov V.V. Mild and moderate cognitive impairment in dyscirculatory encephalopathy // Clinical gerontology. 2005. T. 11. No. 9. P. 38-39. 10. Bogousslavsky J. The global stroke initiative, setting the context with the International Stroke Society // J Neurol Sciences. 2005. V. 238. Supp l.1. IS. 166. 11. Erkinjuntti T., Roman G., Gauthier S. et al. Emerging therapies for vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment // Stroke. 2004. Vol. 35. P. 1010-1017. 12. Erkinjuntti T., Roman G., Gauthier S. Treatment of vascular dementia-evidence from clinical trials with cholinesterase inhibitors // J Neurol Sci. 2004. Vol. 226. P. 63-66. 13. Forrete F., Seux M., Staessen J. et al. Prevention of dementia in randomized double blind placebo controlled Systolic hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur trial) // Lancet. 1998. V. 352. P. 1347-1351. 14. Kumor V., M. Calach. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease with cholinergic drugs // Int J Clin Pharm Ther Toxicol. 1991. V. 29. No. 1. P. 23-37. 15. Hachinski VC, Lassen NA, Marshall Y. Multi-infarct dementia: a cause of mental deterioration in the elderly // Lancet. 1974. V. 2. P. 207. 16. Hansson L., Lithell H., Scoog I. et al. Study on cognition and prognosis in the elderly (SCOPE) // Blood Pressure. 1999. V. 8. P. 177-183. 17. Hershey LA, Olszewski WA Ischemic vascular dementia // Handbook of Demented Illnesses. Ed. by JCMorris. New York etc.: Marcel Dekker, Inc. 1994. P. 335-351. 18. Lovenstone S., Gauthier S. Management of dementia. London: Martin Dunitz, 2001. 19. Golomb J., Kluger A., Garrard P., Ferris S. Clinician's manual on mild cognitive impairment // London: Science Press, 2001. 20. Pantoni L., Garcia J. Pathogenesis of leukoaraiosis // Stroke. 1997. V. 28. P. 652-659. 21. Petersen RS Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment // Arch. Neurol. 2001. Vol. 58. P. 1985-1992. 22. Sahin K., Stoeffler A., Fortuna P. Et al. Dementia severity and the magnitude of cognitive benefit by memantine treatment. A subgroup analysis of two placebo-controlled clinical trials in vascular dementia // Neurobiol.Aging. 2000. Vol. 21.P. S27. 23. Tzourio C., Andersen C., Chapman N. et al. Effects of blood pressure lowering with perindopril and indapamide therapy on dementia and cognitive decline in patients with cerebrovascular disease // Arch Inern Med. 2003. V. 163. N. 9. P. 1069-1075.