Rabies is a vaccine-controlled zoonotic viral disease. At the stage of clinical symptoms, its mortality rate is 100%. Transmission of the rabies virus to humans in almost 99% of cases occurs from domestic dogs. At the same time, not only domestic animals, but also wild animals can suffer from rabies. The infection is transmitted to people and animals through bites or scratches, usually via saliva.

Rabies is present on every continent except Antarctica, with 95% of human deaths occurring in the Asian and African regions. Rabies is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) that predominantly affects poor and vulnerable populations living in remote rural areas. Approximately 80% of human cases occur in rural areas. Although vaccines and immunoglobulins can be used effectively to prevent rabies in humans, they are not always available or accessible to those in need. Worldwide, rabies deaths are rarely reported in official records; Victims of the disease are often children aged 5 to 14 years. With the average cost of a course of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for rabies being US$40 in Africa and US$49 in Asia, such treatment often places a catastrophic financial burden on affected families, whose daily income averages US$1–2 per person [1].

Every year, more than 29 million people worldwide receive rabies vaccinations after animal bites. This is estimated to prevent hundreds of thousands of rabies deaths each year. The global economic burden of rabies transmitted by dogs is estimated at US$8.6 billion per year.

Prevention

Elimination of rabies in dogs

Rabies is a vaccine-preventable disease. The most cost-effective strategy for preventing rabies in humans is to vaccinate dogs. Vaccination of dogs reduces mortality from dog-borne rabies and reduces the need for AEDs in the care of patients injured by dog bites.

Rabies Awareness and Dog Bite Prevention

An important step following the implementation of a rabies vaccination program is public education about dog behavior and bite prevention among children and adults, as this helps reduce both the incidence of rabies in humans and the financial burden associated with treatment for dog bites. To increase public awareness about methods of preventing and controlling rabies, it is necessary to carry out outreach work and disseminate information about the responsibilities of animal owners, ways to prevent dog bites and first aid after a bite. Forming an active position and sense of responsibility among citizens for the implementation of such programs allows for more widespread and effective dissemination of relevant information.

Immunization of people

To immunize people at the stages after exposure to the rabies virus (see PEP) and before it (used less frequently), the same vaccine is used. Pre-exposure immunization is recommended for persons at high risk in the workplace, in particular laboratory technicians handling live rabies virus and related viruses (lyssaviruses); as well as persons who, in the course of professional or private activities, may come into direct contact with bats, predators or other potentially infected mammals (veterinarians, game wardens).

Pre-exposure immunization may also be indicated for ecotourism enthusiasts and persons moving to remote areas with high risks of exposure to the rabies pathogen and limited availability of anti-rabies biological products. Finally, the possibility of immunizing children permanently or temporarily living in remote areas should be considered. When playing with animals, children are at increased risk of serious bites and sometimes do not report bites to adults.

Incubation period after rabies infection

In the process of large-scale research, it was found that the rabies virus enters the bloodstream through the bite of a virus carrier. The virus spreads from the site of the bite to the brain. Virus cells travel both in the bloodstream and along nerve fibers.

Important! Until the virus concentration in the brain reaches a critical mass and neuronal damage begins, the animal does not appear sick.

The incubation period is the time between the bite and the onset of symptoms. Incubation of the rabies virus can last from several weeks to several months. An animal bite during the incubation period does not carry the risk of infection, since the virus has not yet entered the saliva. At the final stage of the disease, the sick dog produces saliva with a huge amount of virus.

At the stage when the virus cells have multiplied in the brain, almost all animals begin to show the first signs of rabies. Most of which are not obvious. Within 3–5 days, when the virus has destroyed enough neurons, the animal begins to show obvious signs of infection.

In almost all countries, an animal that bites a person or other pet must undergo a mandatory quarantine period.

Some countries require this quarantine to take place at an approved animal control facility, while others allow quarantine at the owner's home.

Symptoms

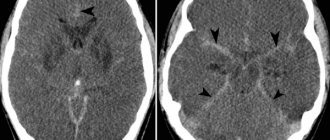

The incubation period for rabies usually lasts 2–3 months, but can vary from 1 week to 1 year depending on factors such as the site of entry of the rabies virus and the viral load. Initial symptoms of rabies include fever and pain, as well as unusual or unexplained tingling, pinching, or burning sensations (paresthesia) at the wound site. As the virus penetrates the central nervous system, progressive, fatal inflammation of the brain and spinal cord develops.

There are two forms of the disease:

- Rabies manifests itself in the form of hyperactivity, agitated behavior, hydrophobia (fear of water) and sometimes aerophobia (fear of drafts or fresh air). Death occurs within a few days as a result of cardiac arrest.

- Paralytic rabies accounts for about 20% of all human cases. This form of rabies is less severe and usually lasts longer than the violent form. It is characterized by the gradual development of muscle paralysis starting from the site of the bite or scratch. Coma slowly develops and death eventually occurs. The paralytic form of rabies is often misdiagnosed, which contributes to underreporting of the disease.

“I played with a little fox and died”

In St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region, fortunately, rabies has not been recorded for the last 25 years. According to the head of the city Veterinary Department Yuri Andreev , we must thank for this the active work on vaccination of both domestic and wild animals. The chief epizotologist, head of the anti-epizootic measures department of the Veterinary Administration, Valeria Yashina, has been working here since the 1980s and remembers very well the case 25 years ago when a soldier died in Petrodvorets from hydrophobia acquired from a wild fox cub.

“The soldiers picked up a little fox somewhere, played with it, and a few days later the little fox died. And a few days later, one of the soldiers fell ill: he had a sore throat, a fever, they tried to diagnose a sore throat, something else... Then they studied the brain of the dead fox and it turned out that it was infected with rabies. The soldier also died - there is no treatment for rabies,” said Valeria Yashina.

vk.com / RK - helping wild animals

She believes that the well-being of St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region in terms of rabies is, unfortunately, an unstable phenomenon. No one is immune from the fact that rabies will be brought to us - as, for example, it was brought to a number of European countries.

“Epidemic outbreaks of rabies occur periodically in Europe, many of which are imported. Animals are brought there, and it is very difficult to keep track of everything. For example, a diplomat brought a dog from Africa infected with rabies to one of the prosperous European countries,” says the veterinarian.

Diagnostics

Currently available diagnostic tools are not suitable for detecting rabies infection before the onset of clinical symptoms of the disease, and diagnosis may be difficult until specific signs of rabies such as hydrophobia or aerophobia appear. Intravital and postmortem confirmation of rabies in humans can be carried out using various diagnostic techniques aimed at identifying the whole virus, viral antigens or nucleic acids in infected tissues (brain, skin or saliva) [2].

How is rabies diagnosed?

In animals, rabies is diagnosed by detecting Rabies virus in any affected part of the brain.

The animal is euthanized . Examination of a suspected animal will help avoid extensive diagnostics of the person who came into contact with it.

In humans , rabies is diagnosed by taking tests of saliva, blood samples, spinal fluid and skin samples. Multiple tests may be required. Research is done to detect proteins on the surface of the virus, detect the genetic material of the virus, or detect antibodies (immune response) to the virus.

Transmission of infection

Infection in humans usually occurs as a result of a deep bite or scratch inflicted by an infected animal, with up to 99% of transmission to humans occurring from rabid dogs.

In the Americas, most human deaths from rabies are now caused by transmission from bats, since transmission from dogs has largely been interrupted in the region. In addition, bat rabies poses an increasing threat to human health in Australia and Western Europe. Cases of human deaths resulting from contact with foxes, raccoons, skunks, jackals, mongooses and other species of wild predatory animals that carry rabies are very rare, and there is no information confirming the transmission of rabies through rodent bites.

Transmission of infection can also occur if the saliva of an infected animal comes into direct contact with mucous membranes or fresh wounds on human skin. Extremely rare cases of rabies infection through inhalation of aerosols containing the virus or through transplantation of infected organs have also been described. Transmission from person to person through a bite or through saliva is theoretically possible, but has never been confirmed. The same applies to people becoming infected by consuming raw meat or milk from infected animals.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves providing first aid to a bite victim after exposure to the rabies virus. It helps prevent the virus from entering the central nervous system, which inevitably leads to death. The PEP is as follows:

- copious rinsing and local treatment of the bite or scratch wound as soon as possible after possible contact;

- a course of immunization with a powerful and effective rabies vaccine that meets WHO standards; And

- if indicated, administration of rabies immunoglobulin (RAI).

Prompt medical care after exposure to the rabies virus is an effective way to prevent symptoms and death.

Copious rinsing of the wound

This type of first aid involves immediately and thoroughly irrigating and washing the wound with soap and water, detergent, povidone-iodine, or other substances that remove and kill the rabies virus for at least 15 minutes.

Risk of exposure and indications for AEDs

Depending on the degree of contact with an animal that may presumably be infected with rabies, a full set of PEP may be recommended according to the following scheme:

| Categories of contact with a suspected rabid animal | Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) measures |

| Category I – touching or feeding animals, animals licking intact skin (no exposure) | Washing exposed skin, no PEP required |

| Category II – compression of exposed skin, minor scratches or abrasions without bleeding (exposure) | Washing the wound and urgent vaccination |

| Category III – single or multiple transdermal bites or scratches, licking of damaged skin; contamination of mucous membranes with saliva from licking, exposure through direct contact with bats (intensive exposure). | Washing the wound, urgent vaccination and administration of rabies immunoglobulin |

A PEP is required for all Category II and III exposures assessed as presenting a risk of developing rabies. The risk increases in the following cases:

- it is known that the mammal that bit a person belongs to a species that is a carrier or vector of rabies;

- the exposure occurred in a geographic area in which rabies is still present;

- the animal appears sick or exhibits abnormal behavior;

- the wound or mucous membrane is contaminated with animal saliva;

- the bite was not provoked;

- the animal is not vaccinated.

If the animal's vaccination status is not definitively established, it cannot be considered as a determining factor in deciding whether to initiate ECP. Such situations are possible when the organization or control of the implementation of dog vaccination programs is unsatisfactory due to lack of resources or low priority of such programs.

WHO continues to actively advocate for the prevention of rabies in humans through the elimination of rabies in dogs, the implementation of strategies to prevent dog bites, and the widespread introduction of intradermal AEDs, which reduce the volume and thus reduce the cost of cultured cell culture by 60-80%. vaccines.

Comprehensive management of bite cases

If possible, the bite should be notified to veterinary authorities, and the biting animal should be identified, isolated, and either quarantined for observation (in the case of healthy dogs and cats) or referred for immediate laboratory evaluation (in the case of dead or euthanized animals with clinical signs). signs of rabies). AED must be continued for a 10-day observation period or until laboratory results are available. Preventive treatment may be interrupted once it is confirmed that the animal is not infected with rabies. The full course of PEP must be completed if an animal with suspected rabies cannot be caught and tested. Veterinary and medical authorities are encouraged to jointly conduct contact tracing to identify other suspected rabid animals and human bite victims so that appropriate preventive measures can be taken.

Main signs of rabies in cats

The latent period of rabies, during which domestic cats do not show clinical symptoms, lasts from 9 days to 2 months. For pets that grew up in the wild, it can last 6 months or more.

The duration of the latent phase of the disease depends on the following factors:

- bite site;

- the amount of pathogen entering the wound;

- depth of damaged tissue;

- the state of the cat’s immune system at the time of infection.

Further, rabies in cats can occur in three forms:

- classical;

- "quiet";

- atypical.

Symptoms of the classic form of feline rabies depend on the period of the disease.

| Period name | Duration | Clinical signs |

| Prodromal period | 1-2 days | A radical change in behavior (affectionate pets begin to show aggression, and evil cats become kind and intrusive), the desire to hide in a dark place, depression, avoidance of contact with the owner and other pets, swallowing inedible objects |

| Excitation period | 2-4 days | Irritability, excessive aggressiveness, muscle tremors, lack of coordination of movements, spasm of the laryngeal muscles, excessive constant salivation, discharge of foamy fluid from the mouth, gnawing on one’s own body |

| Paralysis or "silent phase" | 1 day | Uncoordinated work of the body muscles, convulsions, paralysis and death |

Important! In the fulminant form of rabies, symptoms of the excitation phase may be absent. Minor changes in behavior are abruptly replaced by convulsions, coma and death.

The initial stage of the silent form of rabies in cats is characterized by the following symptoms:

- apathy;

- complete lack of interest in surrounding objects;

- complete refusal of cat food due to the inability to swallow it;

- strabismus;

- asymmetrical change in the radius of the pupils;

- copious salivation.

After 2-3 days, paralysis and death occur.

The atypical form of rabies in cats is manifested by signs that are not characteristic of this disease. Over the course of several months (up to a year), the animal may experience:

- diarrhea followed by constipation and flatulence;

- apathy;

- convulsions;

- paralysis.

Next comes the stage of remission with bouts of relapses. Each subsequent relapse has more pronounced and severe symptoms.

Important! With an atypical form of rabies, when the main symptoms of infection in cats are absent, human infection can occur unnoticed.

WHO activities

Rabies is included in the new WHO roadmap for 2021–2030. The fight against rabies, given the zoonotic nature of this disease, must be carried out within the framework of close interagency cooperation at the national, regional and global levels.

- As part of a comprehensive approach to health, WHO, FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) and OIE (World Organization for Animal Health) have made rabies control a priority.

- The WHO-led Unite to Stop Rabies initiative serves as a multi-stakeholder platform to mobilize and share rabies resources and coordinate global efforts to eliminate rabies in humans, with the goal of achieving zero dog-borne human deaths by 2030 rabies.

- WHO works with a range of partners to provide guidance and support to countries in developing and implementing national rabies elimination plans.

- WHO regularly reviews and disseminates technical guidance on rabies control issues [3], such as epidemiology, surveillance, diagnostics, vaccines, safe and cost-effective immunization [4], strategies for the control and prevention of rabies in humans and animals, and practical implementation of programs [5 ] and palliative care for people with rabies.

- During rabies elimination, countries can ask the WHO to certify that they have achieved zero mortality from dog-borne rabies [3], submit an application for approval of a canine rabies control program to the OIE, or independently declare the elimination of canine rabies [6].

- In 2021, Mexico became the first country to be certified by WHO as having eliminated deaths from rabies transmitted by dogs.

- WHO's priorities to help strengthen the global movement towards universal health coverage include including rabies biologics on national schedules and promoting increased access to AEDs for poor and rural populations.

- In 2021, the GAVI Alliance included human rabies vaccines in its Vaccine Investment Strategy 2021–2025, which will support increased uptake of EPPs for suspected rabies cases in GAVI eligible countries; WHO will continue to provide advice to the Alliance on strategies and methods for introducing rabies vaccine in countries that request it.

- To evaluate the effectiveness of rabies control programs and to increase public awareness and outreach efforts, monitoring and surveillance of such programs is necessary.

The main document that will guide efforts to combat NTDs in the next decade is the Roadmap to combat NTDs for the period until 2030, which indicates phased regional targets for the elimination of rabies [7].

The following principles are key to sustaining rabies control programs and expanding them to surrounding areas: start small, implement local rabies programs through comprehensive incentives, demonstrate program success and cost-effectiveness, and engage government agencies and affected populations.

Elimination of rabies requires sufficient long-term investment. Effective and proven methods of attracting attention and mobilizing political will in this area are demonstrating success on the ground and publicizing the rabies problem widely.

[1] Zero by 30: the global strategic plan to end human deaths from dog-mediated rabies by 2030 [2] WHO, Laboratory techniques in rabies. Fifth edition. Volume 1 and Volume 2 [3] WHO expert consultation on rabies: Third Report. TRS N°1012 [4] Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2021 [5] Scientific and operational updates on rabies [6] OIE Rabies Portal [7] Ending the neglect to achieve the sustainable development goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030