Trigeminal and facial neuralgia

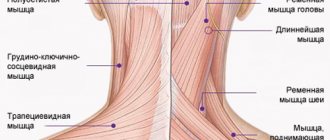

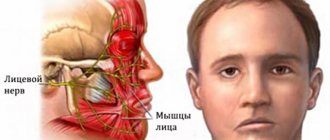

Neuralgia is a disease in which damage or compression of the trigeminal nerve and/or its branches occurs. This causes a sharp piercing pain that occurs suddenly and brings physical and psychological discomfort to the patient. Despite the fact that the term “neuralgia” can be literally translated as “nerve pain,” the matter is not limited to pain. Trigeminal and facial neuralgia are radically different in symptoms. The facial nerve contains mostly motor fibers, so neuralgia leads to dysfunction of the facial muscles (the degree depends on the severity of the disease), and can also cause lacrimation, dry eyes and partial loss of taste. Pain in facial neuralgia is usually concentrated in the area of the parotid gland (the patient complains that the pain radiates to the ear), but there may be no pain at all. It is because of the lack of pain that some experts use the term “neuropathy” when talking about damage to the facial nerve. With the trigeminal nerve it’s exactly the opposite, since it contains many sensory fibers.

Lifestyle and nutrition rules

The diet should be free of foods that unnecessarily irritate the digestive system and taste buds.

Prohibited products include:

- seasonings and spices;

- sauces;

- smoked, salted products;

- fried food;

- fatty meat, lard;

- sweets;

- fast food;

- hot dishes and drinks.

It is also not recommended to eat very hard foods - nuts, crackers . Solid vegetables and fruits must be crushed to a puree or heat treated before consumption.

The diet should consist of simple foods without excess salt. Smoking and drinking alcohol is strictly prohibited.

Symptoms of neuralgia

- Facial pain (prosopalgia). A characteristic sign of neuralgia. Sharp and sudden, reminiscent of an electric shock. Usually lasts from 5 to 15 seconds, is paroxysmal in nature and can occur at any time. During periods of remission, the number of attacks decreases. Most often, pain occurs in the area of the cheekbones and lower jaw (both right and left), and can be localized in almost all areas of the face.

- Impaired sensitivity. A severe form of neuralgia can lead to partial or complete loss of sensitivity of the skin.

- Nervous tic of the eyelid (nystagmus), spasms and twitching of facial muscles.

- Loss of coordination and motor skills are rarer manifestations of severe forms of the disease.

- Headaches, fever, chills and weakness are syndromes caused by viruses and infections.

Causes

Unlike neuritis, neuralgia is not an inflammatory disease. Fever, fever, swelling and other symptoms of the inflammatory process are not associated with this disease. However, if the trigeminal nerve is damaged due to neuritis, pain sensations that fit the description of neuralgia may well occur. To avoid confusion and differentiate the two pathologies, it is necessary to consider their etiology.

The cause of neuritis (like any other inflammatory disease) is viruses and infections that cause gradual destruction of the membrane and nerve trunk, and classical neuralgia in the vast majority of cases occurs due to mechanical effects on the nerve. Today, experts identify dozens of factors that provoke the development of the disease.

Main causes of neuralgia

- Head injuries leading to changes in the cranial structure and displacement of bones.

- Benign and malignant tumors that, as they grow, compress the trigeminal nerve.

- Various bite pathologies and other dental anomalies.

- Pathologies of the structure and diseases of blood vessels located in close proximity to the nerve (atherosclerosis, aneurysm, vasodilatation, etc.).

- Sinusitis and otitis in chronic form.

- Trigeminal neuralgia after tooth extraction. Occurs during a traumatic or incorrectly performed extraction procedure.

- Damage as a result of infection resulting from a number of diseases: periodontitis, periodontitis, stomatitis, herpes, syphilis.

Trigeminal neuralgia from hypothermia occurs rarely. However, this factor contributes to the development of the disease and complicates treatment. The same can be said about decreased immunity, metabolic disorders, neurosis, diabetes and other complicating factors.

Pathogenesis

Doctors identify 2 mechanisms for the development of the disease:

- Due to a disruption in the structure of the nerve fibers, the passage of the nerve impulse slows down, resulting in irritation of the trigeminal nerve.

The nerve, in turn, responds to irritation with pain. - The electrical insulating (myelin) layer of the nerve fiber is disrupted, causing the nerve to become unprotected and vulnerable, and the nerve impulse spreads to nearby nerve fibers and causes pain.

Usually, two mechanisms are involved in the development of pathology; in rare cases, the disease develops according to one of the scenarios.

Classification of the disease

Due to the occurrence

- Primary (idiopathic) trigeminal neuralgia. A classic type of neuralgia, so to speak. Occurs due to compression of the trigeminal nerve.

- Secondary trigeminal neuralgia is a consequence of other diseases and viruses.

By coverage

- Unilateral (one branch of the trigeminal nerve is affected).

- Bilateral (more than one branch is affected).

Neuralgia can affect the 1st, 2nd, 3rd branches of the trigeminal nerve. The first branch is responsible for the orbital zone, the second for the median zone (including the nose and upper lip), and the third for the lower jaw. Most often, damage to the third branch is diagnosed, so the pain affects the area of the lower jaw, and an attack often occurs during hygiene, eating or shaving.

Grigoryan Yu. A., Sitnikov AR

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA AND CEREBELLOPONTINE ANGLE TUMORS

Summary

The optimal treatment strategy for trigeminal neuralgia (TN) associated with cerebellopontine angle (CPA) tumors remains uncertain. The purpose of the work was to determine the relationship of the trigeminal nerve root with space-occupying formations and vascular structures. A retrospective analysis of 211 patients with TN who underwent surgical exploration of the MMU was performed. In 21 (10%) patients, ipsilateral MMU tumors were identified (12 meningiomas, 6 epidermoids and 3 vestibular neuromas). Five different types of compression of the entrance zone of the trigeminal nerve root by tumors and surrounding vessels were discovered. Direct compression of the nerve root only by the tumor (types I and II) was noted in 14 cases, double compression by the tumor and the superior cerebellar artery (types III and IV) - in 6 (4 meningiomas and 2 neuromas), and venous compression without deformation of the nerve fibers by the tumor ( type V) – in 1 case of meningioma. In all cases, the tumors were removed and in 7 additional cases microvascular decompression was performed. Disappearance of TN was observed in all patients without permanent neurological consequences or deaths. TN most often occurs due to direct compression and bending of the trigeminal nerve root by a MMU tumor. In some cases, the cause of pain is double compression by the tumor and the arterial vessel. After removal of MMU tumors, a thorough examination of the trigeminal nerve root entry zone is necessary to assess neurovascular relationships. If concomitant vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve root is detected, neurovascular decompression should be performed to eliminate TN.

Abstract

The optimal management of trigeminal neuralgia (TN) associated with cerebellopontine angle (CPA) tumors is unclear. The aim of this study was to determine relationships between the trigeminal nerve root, CPA mass lesions and vascular structures. Retrospective review of 211 patients with TN treated with CPA exploration was conducted. Twenty one (10%) patients had ipsilateral CPA tumors (12 meningiomas, 6 epidermoids, and 3 vestibular neuromas). Five different types of a trigeminal nerve root entry zone compression by tumors and surrounding vessels were observed. Direct compression of the nerve root by a tumor (types I and II) was noted in 14 patients, dual compression by tumor and superior cerebellar artery (types III and IV) was found in 6 patients (4 meningiomas and 2 neurinomas), and venous compression without distortion of the nerve fibers by tumor (type V) was found in 1 patient with meningioma. All tumors were removed with additional performance of microvascular decompression in 7 patients. Complete relief of TN was achieved in all cases without permanent neurological complications and postoperative mortality. TN can result mostly from direct compression and distortion of the trigeminal nerve root by CPA tumors. In some cases double compression of the nerve by the tumor and the artery can be responsible for facial pain. Careful inspection of the trigeminal nerve root entry zone is strongly recommended after resection of the CPA tumor for estimation of neurovascular relationships. When coexistent vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve root appears, neurovascular decompression is necessary for permanent cure of symptoms.

Key words : cerebellopontine angle, epidermoid, meningioma, neurovascular decompression, neuroma, trigeminal neuralgia

Key words : cerebellopontine angle, epidermoid, meningioma, microvascular decompression, neuronoma, trigeminal neuralgia

The neurological diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is based on specific clinical characteristics of facial pain, such as the duration of attacks, localization and distribution of pain, the presence of a refractory period and trigger zones, a decrease in the intensity and decrease in the frequency of paroxysms when taking anticonvulsants, but does not include the etiological aspects of the occurrence of pain. The morphological basis for the development of neuralgic syndrome is demyelination of the entrance zone of the trigeminal nerve root into the brain stem, accompanied by certain peripheral and central pathophysiological mechanisms, clinically manifested by paroxysmal facial pain. Experience in the surgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, as well as the results of neuroimaging studies, have shown that in the vast majority of cases, the cause of paroxysms of facial pain is vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve root, most often caused by redundant loops of the superior cerebellar artery, as well as other arterial and venous vessels [1 – 7, 12, 17]. In some cases, with trigeminal neuralgia, brain tumors of different structure and location are found, which are considered as the leading etiological factor in the occurrence of facial pain. Tumors, varied in their morphological structure, causing paroxysmal facial pain, are located in various areas of the brain and base of the skull and affect the peripheral branches, ganglion, root and stem structures of the trigeminal nerve. E. Bullitt et al. [9] found 16 brain tumors among 2000 patients with facial pain, and trigeminal neuralgia usually accompanied tumors of the posterior cranial fossa, and atypical variants of facial pain were observed when tumors were localized in the middle cranial fossa and along the peripheral trigeminal branches. Trigeminal neuralgia in tumors of the cerebellopontine angle occurs as a result of direct or indirect mechanical effects of the adjacent tumor on the trigeminal nerve root [3, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 19 – 22, 24 – 28, 31, 33 – 35]. AG Revilla analyzed surgical findings among 473 patients with trigeminal neuralgia operated by WE Dandy and identified tumors of the cerebellopontine angle in 24 (5.1%) cases, with neuromas found in 11 (46%) cases, epidermoids in 9 (38%) and in 4 (16%) - meningiomas [29]. Based on the material of T. Fukushima, the number of tumors of the cerebellopontine angle was 9.5% in a group of 1257 patients with trigeminal neuralgia, and according to FG Barker et al. the frequency of such tumors in the PJ Jannetta series of 1211 patients reached only 2.1% [8, 13]. Direct compression and deformation of the trigeminal nerve root are often observed in benign, slowly growing tumors of the cerebellopontine angle, however, according to PJ Jannetta, trigeminal neuralgia in these cases is of a vascular nature, since paroxysmal pain develops only when nerve fibers are compressed by an adjacent vessel [8, 17]. This paper examines surgical findings in patients with trigeminal neuralgia and neoplasms of the cerebellopontine angle, analyzing the relationship of the trigeminal nerve root with adjacent tumors and vascular structures.

Material and methods . The clinical material is based on 21 patients with tumors of the cerebellopontine angle identified in a group of 211 patients with trigeminal neuralgia who underwent microsurgical exploration of the entry zone of the trigeminal nerve root into the brain stem. The age of the patients ranged from 31 to 74 years (mean 54.3 years), of which 15 were women and 6 men. In all cases, a general clinical and laboratory examination, assessment of the neurological status and MRI of the brain were performed. All patients underwent surgical treatment under endotracheal anesthesia. Surgical interventions were aimed at removing tumors, and the relationship of pathological neoplasms with adjacent neural and vascular structures was documented for subsequent additional analysis. Control CT scans of the brain were performed the next day after surgery, and the final assessment of the radicality of tumor removal was made 7–9 days later based on the results of MRI with contrast.

Results . According to the results of a micromorphological study, the detected tumors of the cerebellopontine angle were represented by meningiomas in 12 cases, epidermoids in 6 cases and neuromas in 3 cases. All patients suffered from unilateral facial pain, the clinical characteristics of which fully met the criteria for trigeminal neuralgia syndrome. In all cases, the tumor of the cerebellopontine angle and trigeminal neuralgia were localized on the same side, in 12 cases on the right and in 9 cases on the left. The age of the patients at the time of manifestation of paroxysmal facial pain was on average 49.6 years (from 23 to 70 years), and the first manifestations of trigeminal neuralgia occurred most early in patients with epidermoids (34 years), and in cases with meningiomas (58.4 years ) and neuromas (54 years old), clinical manifestations developed much later. The duration of the disease before surgery ranged from 2 months to 16 years (average 4.8 years) and the highest value of this indicator was observed in the group of patients with epidermoids of the cerebellopontine angle (6.8 years). Paroxysmal pain syndrome and trigger zones in 9 cases simultaneously involved the maxillary and mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve, and in 3 cases, the entire half of the face. Isolated damage to the mandibular branch was noted in 3 and maxillary - in 6 patients. Thus, in the entire analyzed group of patients, 36 branches of the trigeminal nerve were affected, with the maxillary (18 times) and mandibular (15 times) branches most often involved, and much less often the ophthalmic (3 times). For the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia at the prehospital stage, without conducting studies indicating the presence of a tumor of the cerebellopontine angle, ineffective therapy with carbamazepine drugs was carried out in gradually increasing dosages. Chemical destruction (alcoholization) was carried out in 3 and hydrothermal destruction of the root - in 1 patient, but these procedures did not bring noticeable relief or were characterized by a short-lived, up to 2-4 months, moderately pronounced positive effect. In 1 patient with meningioma of the apex of the temporal bone, stereotactic radiosurgery using the “Gamma knife” installation did not lead to a decrease in pain and a change in tumor size over the next year. In 4 patients who underwent the above manipulations on the peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve, hypoesthesia in the corresponding areas of the face was detected upon admission to varying degrees of severity. Among the remaining 17 patients, a slight decrease in sensitivity on the facial skin and mucous membranes was noted in 10 cases. Trigeminal neuralgia in all 6 patients with epidermoids and in 5 of 12 patients with meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle was the only clinical manifestation of the disease. In the remaining patients with meningiomas (7/12) and neuromas (3/3), facial pain was accompanied by additional neurological disorders, manifested by decreased or loss of hearing, ataxia and nystagmus. Neuroradiological examination showed the presence of space-occupying formations of the cerebellopontine angle with various characteristics. All observed tumors, except epidermoids, according to CT and MRI data, had a round shape and were well contrasted. In the series we presented, the sizes of meningiomas and neurinomas ranged from 1.5 cm to 4.5 cm. The sizes of epidermoids varied from 3 to 6 cm, and in 3 cases there was significant supratentorial spread into the parasellar cisterns, and in 2 cases the tumor masses reached the contralateral cerebellopontine angle. All tumors were removed using a retromastoid approach with the patient sitting with the head bent and turned towards the surgical intervention. The initial site of growth for meningiomas was various lengths of the dura mater from the apex to the internal auditory canal of the pyramid of the temporal bone, and in 4 cases the growth zone extended to the anterolateral parts of the tentorium of the cerebellum near its notch and in 3 cases to the clivus of the skull. All neuromas originated from the vestibulocochlear nerve, and a posterior meatotomy was performed to remove the tumor from the internal auditory canal. In all cases of neurinomas and meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle, the tumor tissue was completely removed. Total removal of tumors was confirmed in these patients using MRI, which did not reveal contrast enhancement of the residual tumor. The epidermoids were completely removed in 5 patients, and in 1 patient, small tumor remains were detected in the area of the contralateral cerebellopontine angle. There were no lethal outcomes after surgical interventions. Postoperative aseptic meningitis in 1 patient with epidermoid was successfully cured with a short course of hormonal therapy. In 2 patients with epidermoid tumors, transient isolated paresis of the oculomotor (1 case) and abducens (1 case) nerves was noted. These disorders regressed within 3 and 4 weeks, respectively, and the most likely causes of the development of these transient neurological complications are intraoperative traction of the nerve roots and spasm of the thin branches of the basilar artery, isolated from the thickness of the epidermoid tumor. In 1 case of meningioma of the apex of the temporal bone, removal of the supratentorial part of the tumor led to the development of isolated paresis of the oculomotor nerve. The oculomotor nerve, stretched at the upper pole of the tumor, was isolated and anatomically preserved, and complete restoration of its functions was noted over the next 2 months. With total removal of neurinomas of the vestibulocochlear nerve, the anatomical integrity of the facial nerve was preserved in all cases, and restoration of the functions of facial muscles was observed within 2 to 3 months of the postoperative period. The primary goal of surgery was to remove tumors of the cerebellopontine angle, and a thorough examination of the trigeminal nerve root entry zone was performed to identify and eliminate a possible vascular cause of trigeminal neuralgia. Microsurgical exploration of the cerebellopontine angle revealed various types of anatomical and topographic relationships between the tumor, the entry zone of the trigeminal nerve root into the brain stem and vascular formations. The various variants of direct and mediated compression effects of tumor nodes on the trigeminal entry zone through vascular formations that we have discovered are schematically divided into five types (Fig. 1).

Types of trigeminal neuralgia

There is an additional classification that can also be used in making a diagnosis.

Acute

Acute trigeminal neuralgia, accompanied by frequent and severe attacks.

Chronic

Chronic trigeminal neuralgia is a consequence of an untreated disease. The patient has been observed for a long time: remissions alternate with exacerbations.

Atypical

Atypical trigeminal neuralgia occurs against a background of stress and nervous exhaustion (psychosomatics).

Postherpetic

Postherpetic trigeminal neuralgia occurs after a history of herpes and its symptoms differ from the classic type. The pain is usually burning and may not go away for two to three hours.

Complications

For fear of provoking a painful attack, patients begin to chew only with the healthy part of the mouth, which causes the formation of compactions in the muscles of the healthy half of the face.

Frequent attacks significantly worsen the quality of life of patients, which affects changes in their psycho-emotional state and performance.

Prolonged and severe pain, being in constant fear of the onset of another attack provoke the development of neurotic and mental disorders (neurosis, depression, hypochondria).

In the case of progressive demyelination and degenerative processes, the trigeminal nerve begins to function worse and worse, the sensitivity and motor activity of the facial and chewing muscles decreases, which leads to its atrophy.

Diagnosis of the disease

Modern medicine has in its arsenal many diagnostic techniques that make it possible to determine the type of neuralgia and the cause of its occurrence:

- visual examination and questioning of the patient;

- X-ray of the jaw;

- MRI of the brain and blood vessels;

- laboratory analysis of urine and blood;

- electromyography.

Diagnosis is carried out by a neurologist, but additional examinations by other specialists are often required: dentist, ophthalmologist, otolaryngologist. Particular attention is paid to differential diagnosis, since neuralgia may resemble other diseases in its symptoms, in particular glaucoma, otitis media, ethmoiditis, Slader syndrome, etc.

Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia

Treatment and drugs

For successful treatment, complex drug therapy is used. First of all, these are anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, finlepsin or clonazepam), which are included in the mandatory rehabilitation program and relieve the main manifestations of neuralgia. The dosage and duration of treatment are determined strictly by the attending physician.

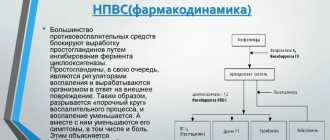

For additional effect, antihistamines and local pain relievers may be prescribed. To compensate for the lack of gamma-aminobutyric acid (a kind of mediator between the brain and the nervous system), baclofen, phenibut or gabapentin are prescribed. In the stage of exacerbation of neuralgia, specialists often prescribe antidepressants to eliminate psychological discomfort (the most common remedy is finlepsin). If the cause of the disease is a virus or infection, antiviral and antibacterial agents, as well as NSAIDs, are prescribed. During the recovery period, it is recommended to take B vitamins.

Physiotherapy

To eliminate pain, novocaine blockades and sodium hydroxybutyrate injections are actively used. The most popular and effective physiotherapeutic techniques: acupuncture, ultraphonophoresis, magnetic therapy, and low-frequency laser therapy. Massage for trigeminal neuralgia is also a good addition to general treatment and allows for better blood circulation.

Methods of treatment and prevention

The following drugs are prescribed to treat the disease:

- anticonvulsants - medications block the conduction of impulses by the trigeminal nerve, which prevents the development of pain (Phenytoin, Oxcarbazepine);

- tricyclic antidepressants - drugs prescribed to prevent chronic pain (Nortriptyline, Amitriptyline);

- muscle relaxants - drugs reduce the tone and relax the muscles of the skull (Mydocalm, Carbamazepam).

Physiotherapy procedures are used to treat trigeminitis:

- magnetic therapy;

- electrophoresis;

- laser treatment;

- acupuncture.

If conservative treatment methods do not produce the desired results, the doctor prescribes surgery.

There are several types of surgical intervention:

- decompression – the doctor changes the position of the arteries that compress the trigeminal nerve;

- destruction of the nerve using chemicals or radio waves;

- nerve root destruction - destruction of a certain part of the nerve using radio waves.

To reduce the risk of pathology, you should follow a number of prevention recommendations:

- protect your head when riding a motorcycle and when engaging in dangerous sports;

- If you receive a traumatic brain injury, immediately consult a doctor and receive treatment;

- avoid hypothermia;

- promptly treat diseases that increase the risk of Fothergill's disease: tuberculosis, sinusitis, diabetes, atherosclerosis, herpes;

- monitor the condition of your teeth and treat them in a timely manner;

- avoid severe stress.

Prevention of exacerbation of an existing disease includes following doctor’s recommendations, taking medications, as well as proper nutrition and lifestyle.