General concept

Meningitis is defined as an acute inflammatory process caused by any infection entering the body. This disease affects people of all age groups.

Reference! The incidence of meningitis in newborns varies from 0.02 to 0.2% . This indicator is influenced by the baby’s weight and general health.

There are several types of meningitis:

- serous. It is characterized by a predominance of lymphocytes in the cerebrospinal fluid;

- purulent. Here, neutrophilic pleocytosis is paramount. In turn, it is divided into two subspecies - primary and secondary. They differ in the places where the infection primarily occurs.

According to statistics, the most common form is secondary purulent and viral meningitis.

A fungal type of disease is also isolated, which occurs in patients with reduced immunity.

If rashes are diagnosed during an illness, this may indicate the probable cause of its appearance.

For example, meningitis is characterized by a skin rash.

Meningitis

Encephalitis

Fungus

Vomit

Rubella

Measles

24535 07 June

IMPORTANT!

The information in this section cannot be used for self-diagnosis and self-treatment.

In case of pain or other exacerbation of the disease, diagnostic tests should be prescribed only by the attending physician. To make a diagnosis and properly prescribe treatment, you should contact your doctor. Meningitis: causes, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment methods.

Definition

Meningitis is an infectious inflammation of the meninges of the brain and spinal cord, accompanied by intoxication, fever, increased intracranial pressure syndrome, meningeal syndrome, as well as inflammatory changes in the cerebrospinal fluid.

The meninges are connective tissue membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. There are dura mater, arachnoid and pia mater.

The dura mater of the brain has a dense consistency and thickness of 0.2-1 mm; in places it fuses with the bones of the skull. The arachnoid membrane is a thin, translucent, non-vascular connective tissue plate that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. The soft shell is a thin connective tissue plate directly adjacent to the brain, corresponds to its relief and penetrates into all its recesses. In its thickness is the vascular network of the brain.

The most common inflammation is inflammation of the pia mater, and the term “meningitis” is used.

Causes of meningitis

The meninges can be involved in the inflammatory process primarily and secondary. Meningitis that occurs without a previous general infection or disease of some other organ is called primary. Secondary meningitis develops as a complication of an existing infectious process. Secondary ones include tuberculous, staphylococcal, pneumococcal meningitis. The primary ones are meningococcal, primary mumps, enteroviral meningitis and others.

The disease is transmitted by airborne droplets, household contact or nutrition.

Purulent inflammation of the meninges can be caused by various bacterial flora (meningococci, pneumococci, and less commonly, other pathogens). The cause of serous meningitis is viruses, bacteria, fungi.

According to the forecast, the most dangerous is tuberculous meningitis, which occurs when there is a tuberculous lesion in the body. The development of the disease occurs in two stages. At the first stage, the pathogen, through the bloodstream, infects the choroid plexuses of the ventricles of the brain with the formation of a specific granuloma in them. In the second, inflammation of the arachnoid and soft membranes is observed (as a rule, the membranes of the base of the brain are affected), which causes acute meningeal syndrome.

The development process of meningococcal meningitis also consists of several stages:

- contact of the pathogen with the mucous membrane of the nasopharynx;

- entry of meningococcus into the blood;

- penetration of the pathogen through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier, irritation of pia mater receptors by toxic factors and inflammation.

The course of the infectious process depends on the pathogenic properties of the pathogen (the ability to cause disease) and the state of the human immune system.

Previous viral diseases, sudden climate change, hypothermia, stress, concomitant diseases, therapy that suppresses the immune system can be significant for the occurrence and course of meningitis.

Classification of the disease

According to the type of pathogen:

- Viral meningitis (influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus, herpes, arbovirus (tick-borne), mumps, enterovirus ECHO and Coxsackie).

- Bacterial meningitis (meningococcal, tuberculous, pneumococcal, staphylococcal, streptococcal, syphilitic, brucellosis, leptospirosis).

- Fungal (cryptococcal, candidiasis, etc.).

- Protozoal (toxoplasmosis, malaria).

- Mixed.

According to the nature of inflammation:

- Serous.

- Purulent.

According to the mechanism of occurrence:

- Primary.

- Secondary.

With the flow:

- Spicy.

- Subacute.

- Fulminant.

- Chronic.

By severity:

- Easy.

- Medium-heavy.

- Heavy.

According to the prevalence of the process:

- Generalized.

- Limited.

According to the presence of complications:

- Complicated.

- Uncomplicated.

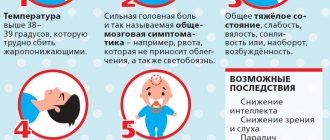

Symptoms and syndromes of meningitis

There are a number of syndromes common to all meningitis:

- meningeal syndrome - manifested by rigidity (increased tone) of the neck muscles and long back muscles, hypersthesia (increased sensitivity) of the sensory organs, headache, vomiting, changes in the cerebrospinal fluid;

- cerebral syndrome - manifested by drowsiness, impaired consciousness, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, psychomotor agitation, hallucinations;

- asthenovegetative syndrome – manifested by weakness, decreased ability to work;

- convulsive syndrome;

- general infectious syndrome - manifested by chills and fever.

Meningococcal meningitis ranks first among purulent meningitis.

Its incubation period ranges from 1 to 10 days, with an average of 2-4 days. The disease usually begins acutely against the background of complete health or shortly after nasopharyngitis. Patients can indicate not only the day, but also the hour of illness; they are worried about chills, body temperature above 38℃, severe bursting headache, aggravated by any noise and movement of the head. Patients may experience pain in various parts of the body, and touching causes excruciating sensations. Vomiting is not associated with food intake and does not bring relief. Soon, stiffness of the neck and long back muscles sets in. Patients take a “meningeal” position. Infants cry constantly, they may experience bulging fontanelles and gastrointestinal disorders. Pneumococcal meningitis, as a rule, is observed in young children against the background of an existing pneumococcal process (pneumonia, sinusitis).

With streptococcal meningitis, hepatolienal syndrome (enlarged liver and spleen), renal failure, adrenal insufficiency, petechial rash (hemorrhages due to damage to the capillaries, as a result of which blood, spreading under the skin, forms round spots, the size of which does not exceed 2 mm).

Purulent meningitis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and fungi are rare. The diagnosis is established only after additional laboratory tests.

Serous tuberculous meningitis is characterized by a gradual onset, although in rare cases it can manifest itself acutely. At the onset of the disease, patients complain of fatigue, weakness, irritability, and sleep disturbances. The temperature is usually no higher than 38℃, and there is an intermittent moderate headache. On the 5-6th day of illness, the temperature rises above 38℃, the headache intensifies, nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness appear. Unconsciousness develops quickly. A divergent strabismus, a low position of the upper eyelid in relation to the eyeball, and pupil dilation may be observed.

When diagnosing mumps meningitis, it is important to identify recent contact with someone with mumps.

Clinical manifestations of damage to the meninges may develop even before the enlargement of the salivary glands.

Enteroviral meningitis is characterized by two- and three-wave fever with intervals between waves of 1-2 or more days. Other manifestations of enterovirus infection are almost always observed (muscle pain, skin rash, herpangina).

For the diagnosis of measles and rubella meningitis, an indication of contact with a patient with these diseases, as well as typical clinical symptoms of measles or rubella, is of great importance.

Diagnosis of meningitis

To confirm the diagnosis of meningitis, the doctor may prescribe a set of laboratory and instrumental studies:

- clinical blood test with determination of hemoglobin concentration, number of erythrocytes, leukocytes and platelets, hematocrit and erythrocyte indices (MCV, RDW, MCH, MCHC), leukoformula and ESR (with microscopy of a blood smear in the presence of pathological changes);

Features of the disease in infants

In newborns, purulent meningitis is mainly detected. It appears due to:

- sepsis;

- trauma during childbirth;

- untimely birth of the fetus.

Often the infection enters the body through the umbilical vessels or through the placenta. The last case is possible when the mother, while pregnant, suffered from pyelitis.

The causative agents of meningitis are:

- coli;

- staphylococci;

- streptococci.

In those who are breastfed, meningitis is considered a severe form of the disease.

In 50% of cases, death is recorded. Adult patients survive in 90% of cases.

Complete lethargy or excessive excitability - these manifestations are very similar to other pathologies.

The diagnosis is confirmed exclusively in a full hospital setting after receiving preliminary results of a cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

It is not always possible to completely cure a baby. A large percentage of complications manifests itself in the form of:

- epilepsy;

- CNS disorders;

- mental retardation;

- paralysis

Such children have to be constantly monitored by doctors and undergo tests to avoid relapse.

If we talk about purulent meningitis, it is an inflammation that forms in the meninges. This subtype ranks first among CNS lesions in newborns. The disease often leads to disability and even death.

It is quite difficult to recognize the disease. A child may be admitted to a medical facility with a common ARVI. Some children experienced local infectious processes.

What do parents need to know about meningitis?

28.06.2018 Meningitis-

This is an inflammation of the soft membranes of the brain and spinal cord caused by various pathogens.

Causes of meningitis:

· Viruses (eg, measles, chickenpox, mumps). · Bacteria (for example, meningococcus, pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae and others). · Fungi.

All types of meningitis have symptoms that are common to common infections. It is almost impossible to identify the cause of the disease without laboratory diagnostics.

Meningococcal infection

is one of the most pressing problems, with approximately half a million cases reported annually worldwide, one in ten of which are fatal. Death in 63% of cases occurred on the first day from the onset of the disease, even with timely seeking medical help, most of them were children under 2 years of age. In 20% of cases after meningococcal infection, the outcome was disability (loss of hearing, vision, mental retardation, amputation of limbs).

Meningococcal infection

is an acute infectious disease caused by the bacterium meningococcus.

The disease can manifest itself in different ways:

- Asymptomatic carriage (meningococci can inhabit the human nasopharynx and any of us can be a potential carrier; carriage is more common in adults and adolescents, who are the source of infection for children),

- Mild respiratory infection (nasopharyngitis),

- Severe forms of infection (meningitis, sepsis).

Who can get sick?

Meningococcal meningitis can occur in any person - a child of the first year of life, a teenager and an adult. Meningococcal infection is especially dangerous for children. In more than 90% of cases, healthy children without additional risk factors get sick; the incidence of children under 4 years of age is 22 times higher than in adults!

Sources of infection.

The disease spreads from person to person through coughing, sneezing, kissing, and even talking or sharing cutlery. Since infection occurs through close contact, the main source of infection for young children is their parents, brothers and sisters, relatives, as well as other children in nurseries and kindergartens.

Risk factors for meningococcal infection:

- child's age up to 4 years;

- visiting a kindergarten or school;

- cramped living conditions: in a family, in dormitories, barracks, boarding schools, orphanages, sanatoriums, pioneer camps, etc.;

- external factors leading to a weakening of the immune system (including stress, hypothermia, overwork);

- congenital and acquired disorders of the immune system, damage or absence of the spleen;

- traveling to places where meningococcal infection is widespread (some African countries, Saudi Arabia).

1. Fever.

One sign of meningitis is a fever that starts suddenly. The child begins to tremble and complains that he is cold all the time.

The patient's temperature quickly rises, which can be difficult to bring down. But since this symptom is a sign of many diseases, you should also pay attention to other features in the change in the child’s condition.

2. Headache.

Headache with meningitis is often not just severe, but almost unbearable. In this case, the pain often also constrains the patient’s neck, but due to the fact that the patient’s head literally “splits,” he may not pay attention to it.

In newborns, a characteristic sign is also a bulge in the area of the large fontanelle and a high-pitched cry.

3. Double vision.

A patient with meningitis cannot focus his vision, which is why the image in his eyes constantly doubles.

4. Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, sudden loss of appetite.

5. Photosensitivity.

Another sign of meningitis is a fear of bright light, which can cause the child's eyes to water, as well as worsening nausea and headaches.

6. Stiff neck.

A child with meningitis is in a special recognizable position: lying on his side with his head thrown back and legs bent. When he tries to straighten his neck, he often fails.

7. Inability to straighten your legs.

Even if it is possible to tilt the child’s head to the chest, his legs immediately bend at the knees, which are impossible to straighten in this position. This phenomenon is called upper Brudzinski syndrome.

With meningitis, Kernig's syndrome also appears along with it. With it, it is impossible to straighten the leg at the knee if it is raised approximately 90°.

8. Skin rashes do not turn pale.

With meningitis, skin rashes are also possible. A simple test can help distinguish them from rashes that are not associated with meningitis. Take a glass of clear glass, apply it to the rash and press so that the skin under the glass turns pale. If the rash also turns pale, it means there is no meningitis. If the rash has retained its color, you should be wary.

How to protect your child from meningococcal infection?

It is impossible to completely protect a child from contact with infections. Therefore, vaccination is carried out to protect against infectious diseases. A child can be vaccinated against meningococcal infection in the first year of life (from 9 months).

Children from the risk group are subject to vaccination (see above).

Facts about meningitis vaccines.

Meningococcal vaccines do not contain live bacteria and cannot cause meningococcal disease in unvaccinated people.

Vaccines create an immune response even in young children, which will protect the child from a dangerous infection as early as possible.

The vaccine provides a stable immune “barrier” against meningococcal infection 10 days after vaccination.

The vaccine also reduces the carriage of bacteria in the nasopharynx. By vaccinating yourself, adults can prevent transmission of bacteria to young children, who are at particular risk!

There are several types (serotypes) of meningococcus, the most common of which are A, B, C, Y and W. That is why it is advisable to choose vaccines that include the maximum number of meningococcal serotypes for more reliable protection against infection. The Menactra vaccine, approved in the Russian Federation, meets these requirements.

, providing protection against serotypes A, C, Y, W-135 (made in the USA).

Vaccination schedule

from 9 months. up to 23 months twice, with an interval of at least 3 months; from 2 years to 55 years once. Revaccination is not required.

The Baxero vaccine can protect against serotype B, which is widespread in Russia.

, but the drug is not registered in the Russian Federation. Maybe someday it will appear here too, but we shouldn’t expect it in the coming years. Two European countries have included Bexero in their national vaccination schedules - the UK and the Czech Republic. Vaccination of Russians with this drug is possible in European countries at their own expense (vaccine tourism).

In the pediatric department of Clinical Hospital No. 122, vaccination against meningitis is carried out by the head of the pediatric department, pediatrician, pulmonologist L.V. Marshalkovskaya. and pediatrician, allergist-immunologist Pereverzeva Yu.S.

The material was prepared by a pediatrician, allergist-immunologist

Pereverzeva Yulia Sergeevna

.

To prepare the material, the following sources were used: Pediatrics according to Nelson, 17th edition, 244, p. 398, Internet sources: https://www.privivka.ru/meningit, https://www.adme.ru.

Regarding vaccination against meningitis

at the pediatric department of clinical hospital No. 122

please contact us by phone:

+7(812)363-11-22;

+7(812) 558-99-76,

Pediatric department

Causes

The causes of the disease can be provoked by different pathogens. If we talk about babies, they are as follows:

- hemophilus influenzae;

- pneumococcus;

- meningococcus;

- enterobacteria;

- microbacteria tuberculosis.

Meningitis is transmitted by household contact, airborne droplets, vertical, transmissive, alimentary and waterways . The disease develops against the background of a difficult pregnancy and difficult childbirth.

Reference! Outbreaks of meningitis in older children tend to be seasonal. Typically the peak occurs in winter and spring.

Symptoms in children

The clinical picture of the disease is represented by general neurological symptoms. These include the following:

- decreased physical activity;

- general lethargy;

- increased drowsiness;

- frequent vomiting;

- refusal of breast milk;

- signs of suffocation.

Newborns can suffer from temperatures exceeding 39 degrees. In some, the signs can be recognized if, when tilting the head back, convulsions appear or an increased pulsation of the fontanel is observed.

How does meningitis occur in a low-weight child? Here the clinical picture is completely different. It will make itself felt especially at the peak of the disease. At risk, first of all, are infants born prematurely and those who are already given antibiotics in the maternity hospital to maintain viability.

Important! The disease itself is characterized by rapid development. Depending on age and weight, it can also be protracted. All this creates a number of difficulties for doctors in timely and correct diagnosis of the disease.

Meningococcal infection in children

Meningococcal infection can present with a variety of symptoms. There may be a localized form of the disease - acute nasopharyngitis; generalized forms - meningococcemia, meningitis; mixed form - meningitis in combination with meningococcal disease; rare forms - meningococcal endocarditis, meningococcal pneumonia, meningococcal iridocyclitis, etc.

The incubation period lasts from 2 to 10 days.

Acute nasopharyngitis is the most common form of the disease (80% of all cases of meningococcal infection). It begins acutely, body temperature reaches 37.5-38.0 °C. The following symptoms appear: headache, dizziness (not always), pain when swallowing, sore throat, nasal congestion, adynamia, lethargy, pale skin.

The pharynx is hyperemic, the back wall of the pharynx is swollen, with a small amount of mucus.

Often the body temperature does not rise, and the child’s general condition is satisfactory, catarrhal symptoms in the pharynx are very mild. A blood test sometimes shows moderate neutrophilic leukocytosis, but in ½ cases the blood composition is unchanged.

The course of nasopharyngitis is favorable, the temperature returns to normal after 2-4 days. The child recovers on the 5-7th day. Meningococcal nasopharyngitis in some cases may be only the initial symptom of a generalized form of the disease.

Meningococcemia (meningococcal bacteremia, meningococcal sepsis) is a clinical form of meningococcal infection, which, in addition to the skin, can affect various organs (adrenal glands, kidneys, lungs, spleen, eyes, joints).

Meningococcemia has an acute onset, sometimes sudden, and body temperature quickly rises to high levels. The child is shivering, has a severe headache, and repeats vomiting. Since infants cannot talk about a headache, this symptom manifests itself in them with a high-pitched scream and crying.

In more severe cases, loss of consciousness is possible, and in young children - convulsions. Symptoms increase over 1-2 days. At the end of the first or at the beginning of the second day of the disease, a hemorrhagic rash appears all over the body, but the largest amount is concentrated on the buttocks and legs.

In areas of extensive lesions, necrosis is subsequently rejected and defects and scars form. There may be joint damage in the form of synovitis or arthritis. Usually changes are found in the small joints of the fingers, toes, and less often in large joints. Children may complain of pain in the joints, sometimes their swelling and hyperemia of the skin over the joints are visually noticeable.

Uveitis and iridocyclochoroiditis develop in the choroid of the eyes. When the heart is damaged, symptoms such as cyanosis, shortness of breath, dullness of heart sounds, expansion of its borders, etc. appear.

A blood test for meningococcemia shows high leukocytosis, neutrophil shift, and increased ESR.

Meningococcemia comes in the following forms: mild, moderate and severe. The most severe form is considered to be fulminant. In such cases, the disease begins abruptly, the body temperature rises, and a profuse hamorrhagic rash appears, the elements of which quickly merge, becoming similar to cadaveric spots. The child's skin is pale and cold to the touch, facial features become sharper. Blood pressure decreases greatly, tachycardia, thready pulse, and severe shortness of breath are observed. Meningeal symptoms are variable. At the final stage, vomiting appears in the form of “coffee grounds.”

Acute swelling and edema of the brain may occur, which is manifested by symptoms such as severe headache, convulsions, loss of consciousness, psychomotor agitation, and repeated vomiting. If timely therapy is not carried out, death occurs 12-24 hours after the onset of the disease.

Meningococcal meningitis is another form of the disease that begins acutely, with severe fever and severe chills. Symptoms such as headaches that do not have a clear location, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and screaming appear. Excitement in some children may be replaced by lethargy and indifference to the environment.

Pain along the spine may occur. When touched, the pain intensifies. Hyperesthesia is one of the characteristic and most manifest symptoms of purulent meningitis. Another important symptom is vomiting, which is not associated with meals and starts from the first day of the disease.

With meningococcal meningitis in young children, an important symptom is convulsions, which appear from the first day of illness. On the 2-3rd day, meningeal symptoms begin.

Most often, tendon reflexes are increased, but may be absent in severe intoxication. The appearance of focal symptoms indicates edema and swelling of the brain. With meningococcal meningitis, the child's face is pale, with an expression of suffering, and there is a slight injection of the sclera. An increase in heart rate, muffled heart sounds, and a decrease in blood pressure are also recorded. In severe forms, breathing is shallow and rapid. Young children may experience diarrhea from the first days, which complicates diagnosis. A blood test shows leukocytosis, neutrophil shift, aneosinophilia, and increased ESR. There are also changes in the urine: cylindruria, slight albuminuria, microhematuria.

Changes in the cerebrospinal fluid are important for diagnosis. At the very beginning of the disease, the fluid is clear, but quickly becomes cloudy and purulent due to the high content of neutrophils. Pleocytosis is large, up to several thousand in 1 μl.

Meningococcal meningoencephalitis is a form of meningococcal infection that occurs mainly in young children. From the first day of the disease, encephalitic symptoms are observed in this form: impaired consciousness, motor agitation, damage to III , VI , V, VIII , less often other cranial nerves, convulsions. There is a possibility of monoparesis, bulbar palsy, cerebellar ataxia, and oculomotor disorders. The disease has a severe course and often ends in death.

Meningococcal meningitis and meningococcemia . Most patients have a combined form of meningococcal infection - meningitis with meningococcemia. Symptoms of meningitis and meningoencephalitis, as well as symptoms of meningococcemia, may come to the fore.

Course and complications . The course of meningococcal infection without etiotropic therapy is severe and long-lasting - as a rule, up to 4-6 weeks and even up to 2-3 months. There are cases (and they are not uncommon) when the disease has a wave-like course - periods of improvement and deterioration occur. During any period, the patient's death may occur.

In young children, the course of the disease may be aggravated due to cerebral hypotension syndrome. At the same time, facial features become sharper, eyes become sunken, dark circles form around them, and symptoms such as hypotension and convulsions are recorded. Meningeal symptoms weaken or do not appear, tendon reflexes fade.

The course of meningococcal meningitis can become significantly more severe if the inflammatory process spreads to the ependyma of the ventricles of the brain. Ependymatitis is manifested by clinical symptoms of meningoencephalitis: motor restlessness, drowsiness, prostration, hyperesthesia, etc. The child's pose is characteristic: legs are extended, shins are crossed, fingers are clenched into a fist.

There are mild abortive variants of the disease. They are characterized by mild symptoms of intoxication and unstable meningeal symptoms. For diagnosis, a spinal tap is necessary.

Treatment methods

Treatment of meningitis is a very long and serious process. Attempting to administer any medications at home is strictly prohibited.

Important! The disease is treated strictly in a hospital. Folk remedies will not help get rid of the disease . All therapy should begin with establishing the root cause of meningitis.

When doctors diagnose a bacterial infection, they will most likely prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics. As a rule, medications are administered in maximum dosages over a long course. Change medications every 12 weeks.

When the disease takes the form of a viral and fungal infection, then antiviral and antifungal drugs are administered. All injections in this case are intravenous.

If there is a fungal or viral infection, the baby may recover in 14-20 days. The bacterial type of meningitis takes the longest to treat. In general, the course depends on the severity of the disease and the general condition of the body.

Meningitis is dangerous, but curable

What you need to know about meningitis. And why you shouldn’t hesitate to go to the hospital

Since the beginning of this summer, outbreaks of meningitis have been recorded in several regions of Russia. The disease primarily affects children and, although meningitis is rare in Ugra, every person should have a general understanding of the symptoms and dangers of this disease. This concerns parents first of all.

| Meningitis (from the Greek meninx - meninges), inflammation of the membranes of the brain and spinal cord. Meningitis is classified according to the causative agent of the disease (viral, bacterial, fungal, tuberculosis, syphilitic, etc.), course (acute, subacute, chronic), and the nature of changes in the cerebrospinal fluid (purulent and serous). |

You can get meningitis at any age. Rather, the incidence does not depend on age, but on the condition of the body. For example, premature babies are primarily at risk of meningitis. Babies born prematurely are exposed to meningitis much more often, which is explained by weakened immunity. Also, the group of people who are more susceptible to the disease includes people with various defects of the central nervous system, with head or back injuries. Children who have disturbances in the functioning of the nervous system are at risk, and the more serious the disease is in a child, the greater the likelihood of developing meningitis. In general, there are many factors that, one way or another, influence morbidity.

Did you suspect? Call!

Head of the children's infectious diseases department of the District Clinical Hospital of Khanty-Mansiysk, infectious disease doctor of the highest qualification category Alena Kurganskaya - “Meningitis is an inflammatory disease of the brain. The source of infection can be any sick person carrying viruses or bacteria, as well as water and food products. The disease manifests itself with symptoms characteristic of any infectious process. This is a high temperature - within 39-40 degrees, nausea and vomiting. Unfortunately, it is almost impossible to bring down such a high temperature with conventional antipyretics. A headache that an older child can bring to the attention of parents. In addition, one of the characteristic features of meningitis in more severe forms is a state of stunning; the child may not respond to treatment. In especially severe cases, the course of the disease can reach comatose states. The consequence of meningitis can be the formation of paresis, paralysis, and sometimes disability. At the same time, timely seeking medical help allows for a complete recovery without complications.”

If the disease was detected in a timely manner, and doctors took all the necessary measures aimed at eliminating it, meningitis is not accompanied by serious consequences. As a rule, after treatment, the child can lead a normal life, since the main body systems were not damaged.

“Therefore, if a child experiences the symptoms described above, parents should immediately seek medical help from doctors,” says Alena Kurganskaya, head of the children’s infectious diseases department. - This applies to fever, headache, nausea and vomiting. You also need to carefully note changes in the child’s behavior. So, some children cry tirelessly and are too excited, while others, on the contrary, are too lethargic and can sleep for a long time. An excited state, monotonous crying are also symptoms. Violation of contact between parent and child should alert you - this may be associated with the development of an acute infectious process associated with damage to the central nervous system or meningitis. Of course, fever, headache and some other symptoms can accompany any other infectious disease. But even in this case, going to the hospital or calling a local pediatrician is mandatory! Of course, it is impossible to get meningitis unnoticed. From my personal experience, I can say that I have never seen a case where a person suffered any kind of neuroinfection on his legs without consulting a doctor.”

Diligence and Prevention

“Meningitis can be of viral or bacterial etiology,” says the head of the children’s infectious diseases department. — In the spring-summer period, there is an increase in viral infections - serous, not very severe meningitis of a viral nature occurs, the source of which can be either a sick person or carriers from wildlife - ticks (a complication of tick-borne encephalitis), mosquitoes. In the cold season, meningitis of bacterial etiology, caused, for example, by meningococcal infection, is more common.

As for places with an increased risk of disease, they cannot be strictly designated - the source is people who may be healthy carriers of a particular virus or bacteria, or with acute manifestations of the disease. Therefore, when visiting the same kindergarten where the child comes into contact with many children, the risk of infection increases. Naturally, kindergartens are always a risk of getting any infectious disease. Infection can also occur through water.

Isolated cases of meningitis are registered in Ugra. If we talk about outbreaks of the disease that were registered in the Krasnodar and Stavropol Territories, the sources of infection have been identified by specialists - this is precisely the waterway. The warm region encourages children to swim and come into contact with the water of large bodies of water. Therefore, the chance of infection increases. Hence the mass infection.

As for prevention, protecting a child from meningitis will be possible by following general hygiene rules and a cautious approach to recreational areas on the water; if we are talking about vacations in the South, swimming pools will be much safer than open water. In any case, if it is known that cases of the disease have been recorded in this region. In addition, if we take enterovirus infection into account, the disease can also be transmitted through food. Therefore, thoroughly washing fruits and vegetables is a must. Contacts with persons showing signs of infectious diseases should be avoided.”

article from the site https://cmphmao.ru/node/191

Possible effects in infants

This extremely dangerous disease often results in the most negative consequences for the baby. Sometimes even long-term therapy becomes powerless. The consequences include:

- blindness;

- deafness;

- bleeding disorders;

- mental retardation;

- Within two years, a brain abscess may occur.

Reference! Infants die in 30-50% of cases if a brain abscess is detected.

Even if the child manages to survive, complications will be felt for a long time. When the disease is mild, the course of treatment is several weeks if it started on time.

We invite you to watch an interesting video on the topic:

Features of antibacterial therapy in premature newborns

AND

Infectious and inflammatory diseases are the most common pathology in children of the neonatal period, which is explained by the uniqueness of protective mechanisms at this stage of ontogenesis. The most pronounced deficiency of humoral and cellular immunity, immaturity of the barrier functions of the skin and mucous membranes in children born prematurely. In the structure of diagnoses in departments of the second stage of nursing premature babies, the proportion of purulent-inflammatory diseases approaches 80%, with the majority of diseases being so-called minor infections - pustular rashes, omphalitis, dacryocystitis, otitis media; In 1% of children, serious inflammatory diseases are detected (cellulitis and pemphigus of newborns, osteomyelitis, meningoencephalitis, pneumonia, sepsis).

In recent years, the problems of infectious pathology in immature children have become particularly relevant due to changes in the characteristics of both macro- and microorganisms, which affected the course of the infectious process. The course of background conditions has become more severe, creating favorable conditions for the manifestation and progression of infection - these are perinatal brain lesions, congenital malformations, pneumopathy; Moreover, the achievements of modern resuscitation and intensive care make it possible to ensure the survival of even children with extremely low body weight who have suffered severe asphyxia. In turn, resuscitation measures, primarily long-term mechanical ventilation and catheterization of the great vessels, create conditions for microbial aggression. One of the important factors contributing to bacterial contamination and aggravation of the course of bacterial infections is the presence of a mixed viral-bacterial intrauterine infection. Intrauterine parasitic and viral infections (the so-called TORCH syndrome) are the main cause of mortality in the neonatal period in 13–45% of cases. A specific infection transferred in utero sharply disrupts the child’s defense mechanisms, which contributes to the occurrence and rapid course of intranatal and postnatal bacterial infections.

Modern etiology of pathogens

In the etiological structure of pathogens of bacterial infections in premature infants 10–15 years ago, there was an increase in the proportion of gram-negative flora (Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas). However, in subsequent years, again among the etiological agents of local purulent-inflammatory lesions, the first place is occupied by gram-positive flora

(staphylococci, streptococci).

Premature babies are characterized by a combination of microorganisms

isolated from various foci (for example, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are sown from a purulent focus, Escherichia coli and staphylococci are sown from feces), as well as

a change in the leading pathogens during treatment

(the initial agents of inflammation are suppressed, others take their place bacteria, often in combination with fungi).

Predominantly antibiotic-sensitive strains of pathogens circulate among the population (V.K. Tatochenko), and in hospitals children are infested with predominantly resistant strains (nosocomial flora), since opportunistic and saprophytic microorganisms are repeatedly passaged on weakened immature newborns and their selection occurs under the influence therapy (G.V. Yatsyk, I.V. Markova). In addition, resistant strains (Klebsiella, Streptococcus B) are transmitted to newborns from sick mothers.

Specifics of antibiotic pharmacokinetics

In newborns, the pharmacokinetics of any drug differs significantly from that in older children; This applies to the greatest extent to immature (premature) newborns. The immaturity of the excretory function of the kidneys and liver enzyme systems seems extremely important

These features are primarily characteristic of very premature infants weighing less than 1500 g. In addition,

the immaturity of other organs and systems

(gastrointestinal tract, nervous system, respiratory organs), as well as general

metabolic lability

, impose individual differences on the pharmacokinetics of antibiotics in premature infants. features predetermining a high risk of unwanted side effects of antibacterial therapy.

A general feature of the pharmacokinetics of any drugs in premature infants is its slowdown, which contributes

to the accumulation of drugs and affects the choice of dose (reducing it by 1/3–1/4), routes and frequency of drug administration.

At the same time, the increased permeability of natural barriers

(skin and mucous membranes) facilitates the absorption of many medications. Currently, studies are being conducted on the circadian rhythms of the pharmacodynamics of various drugs, but there are practically no such studies regarding antibiotics in premature infants.

Indications and choice of antibiotic

An absolute indication for prescribing antibiotic therapy to a premature newborn is the presence of any infectious-inflammatory process, including so-called minor infections, for example, non-spread pustular skin lesions, purulent conjunctivitis, otitis (including catarrhal otitis). Only in rare cases of a mild course of uncomplicated acute respiratory viral infection (rhinopharyngitis) is an antibiotic not prescribed - and then only in children with a relatively favorable background (slight degree of prematurity, no anamnestic indications of intrauterine infection, mild perinatal encephalopathy).

An absolute indication for antibiotic therapy for a premature newborn is the presence of any infectious-inflammatory process, including so-called minor infections, for example, non-spread pustular skin lesions, purulent conjunctivitis, otitis (including catarrhal otitis). Only in rare cases of a mild course of uncomplicated acute respiratory viral infection (rhinopharyngitis) is an antibiotic not prescribed - and then only in children with a relatively favorable background (slight degree of prematurity, no anamnestic indications of intrauterine infection, mild perinatal encephalopathy).

The controversial issue of the so-called prophylactic use of antibiotics

in low birth weight premature babies at risk for intrauterine and intrapartum infection (sick mother, long anhydrous period, etc.), as a rule, it is decided in favor of prescribing an antibiotic, as well as in cases of so-called non-infectious pneumopathy. Conditionally “preventive” can also include the prescription of an antibiotic to “cover up” hormonal corticosteroid therapy and certain interventions (catheterization, blood transfusion, etc.).

The choice of antibiotic for a premature baby is a crucial moment that largely determines the effectiveness of treatment. When choosing a drug, the following factors should be considered:

• type of pathogen

(at the beginning of treatment, often only suspected) and its strain;

• pathogen sensitivity

(also at the beginning of treatment - expected, 2-3 days after receiving the results of bacteriological tests, adjustments may be made to the therapy). In recent years, an opinion has been expressed that the sensitivity parameters of microbes in vitro do not always coincide with those in vivo and there is no need to strictly follow them when prescribing drugs;

• localization and severity of the infectious process

(for mild local lesions, oral administration of the drug is possible; for severe ones, as a rule, a combination of oral and parenteral drugs);

• accompanying conditions and premobid background

(preference for parenteral drugs in severe dysbiosis or intravenous administration in extremely low birth weight children with undeveloped muscle tissue).

All antibiotics can be divided into 2 groups - first choice drugs

prescribed when there is no reason to think about the drug resistance of the flora (semi-synthetic penicillins, first generation aminoglycosides, first generation cephalosporins);

second-choice drugs

are aimed at overcoming resistant strains (aminoglycosides and cephalosporins of the III–IV generation, modern macrolides).

There are also third-choice drugs (or reserve drugs

) used for extremely severe forms of diseases with multidrug-resistant flora (carbapenems).

In premature babies, second-choice drugs are generally immediately used: the use of first-line antibiotics is ineffective and only helps to delay the manifest manifestations of the infectious process and masks clinical symptoms. In children of the neonatal period, even for health reasons, drugs with high toxicity (fluoroquinolones) should not be used.

Scheme 1. Acceptable combinations of antibiotics in premature infants with simultaneous use (G.V. Yatsyk)

Features of antibiotic dosage

Dosages of antibiotics used in neonatology for premature infants and the frequency of their administration are presented in Table. 1 (G.V. Yatsyk, 1998) The general principle of dose selection for a newborn child is a larger amount of the drug per 1 kg of body weight compared to older children

– persists in premature babies.

This is due to the higher percentage of water in the newborn’s body and the larger relative surface area of the body. The dosages of antibiotics used in neonatology for premature babies and the frequency of their administration are presented in Table.

1 (G.V. Yatsyk, 1998) The general principle of selecting a dose for a newborn baby remains the same for premature babies. This is due to the higher percentage of water in the newborn’s body and the larger relative surface area of the body. Combination therapy

Combined antibacterial therapy in premature infants should be carried out with great caution; a simultaneous combination of 2 (very rarely - 3) antibiotics is used only in children with severe purulent-inflammatory processes (primarily sepsis) caused by mixed flora. Acceptable combinations of antibiotics are presented in table. 2 and in diagram 1 (data from N.V. Beloborodova).

Routes and frequency of administration of antibiotics to a premature baby

Due to the high permeability and vulnerability of the gastrointestinal mucosa in immature newborns, as well as the risk of developing dysbiosis and necrotizing ulcerative enterocolitis, oral antibiotics have been used to a limited extent. In addition, most infectious diseases in premature infants require more powerful therapy due to the severity of their condition. In recent years, quite effective antibacterial and antifungal drugs for oral use have appeared (macrolides, amoxicillin/clavulanate, etc.). In addition, the extremely negative impact of painful irritations on infants has been established, which makes it necessary to limit intramuscular and intravenous injections

.

In newborns (especially premature babies), the half-life of drugs is increased due to the immaturity of the kidneys and liver. Therefore, the frequency of administration of most drugs does not exceed 2 times during the day.

(except penicillins); Long-acting drugs (roxithromycin, ceftriaxone), which can be used once, remain especially popular in neonatology. Some researchers (N.V. Beloborodova, O.B. Ladodo) suggest administering most parenteral drugs (including aminoglycosides, cephalosporins) once - intravenously or intramuscularly.

Duration of therapy

The duration of antibacterial therapy and the sequence of antibiotics used in a premature baby are determined individually; they depend on the effectiveness of the initial course of antibacterial therapy, which is assessed using traditional clinical and laboratory parameters. As a rule, premature infants with moderate infectious processes (omphalitis, pneumonia, otitis, etc.) are given two consecutive courses of antibiotics (the second course taking into account the sensitivity of the microflora), each lasting 7–10 days. For severe diseases (meningitis, osteomyelitis, sepsis), at least 3–4 courses of antibiotics are usually used (or 2–3 courses; in the first, a combination of antibiotics, usually an aminoglycoside and a III–IV generation cephalosporin).

Side effects and their prevention

The most common undesirable side effects of antibacterial therapy in premature newborns are caused by suppression of symbiont microflora and, as a consequence, colonization of the body by opportunistic saprophytes. In this regard, even after a short course of antibacterial therapy, premature infants may develop dysbiosis

– candidiasis of the skin and mucous membranes, intestinal dysbiosis.

toxic

(idiosyncrasy-type) and

allergic reactions

to antibiotics are observed in premature infants

Prevention of complications of antibacterial therapy begins with its correct selection and careful individual monitoring. Along with prescribing antibiotics, the child must be prescribed antifungal agents.

(levorin, fluconazole, amphotericin B) and

agents that restore intestinal microflora

(bifidum-bacterin, etc.);

Moreover, the use of the latter continues for at least a week after the end of the course of antibiotics. In order to reduce the load of antibiotics on the immature body of a premature baby, in recent years attempts have been made to combine antibacterial therapy with agents that enhance nonspecific protection : immunoglobulins, laser therapy (the use of low-intensity laser radiation on great vessels for the purpose of immunostimulation), and metabolite correction.

Forecast

The prognosis should be determined based on the etiology, premorbid background and severity of the disease. The adequacy and timeliness of therapy is of no small importance.

Modern medicine has reached such heights that there are fewer and fewer deaths among infants. As for the residual period of meningitis, hypertensive and asthenic syndromes are more often recorded in children.

Important! Infants who have had this disease should be registered with a neurologist, infectious disease specialist, or pediatrician.

Intrauterine infection - symptoms and treatment

The manifestation of infection directly depends on the timing of infection. For all intrauterine infections there are a number of common symptoms [1][6]:

- The first 2 weeks after conception are spontaneous early abortions.

- From 2 to 10 weeks - gross malformations incompatible with life (severe heart defects, brain defects, etc.), as a result, spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) or frozen pregnancy.

- From 10 to 28 weeks - early fetopathies (diseases and malformations of the fetus). A miscarriage or frozen pregnancy is possible.

- From 28 to 40 weeks - late fetopathies. Development of inflammation in different organs.

- During childbirth - inflammation in organs (myocarditis, pneumonia, etc.).

The presence of an intrauterine infection in a child can be suspected during childbirth. Infection may be indicated by the discharge of cloudy amniotic fluid with an unpleasant odor or meconium (newborn feces). Children with intrauterine infection are often born prematurely and develop asphyxia (oxygen starvation). From the first days, such children also experience:

- jaundice;

- low birth weight (less than 2.5 kg);

- various skin rashes;

- respiratory disorders (pneumonia, respiratory distress syndrome);

- lethargy;

- pale skin;

- febrile conditions or hypothermia (body temperature below 36.0 °C);

- cardiovascular failure;

- neurological disorders (decreased muscle tone, convulsions, bulging large fontanel, high-pitched scream, increased excitability);

- decreased appetite, delayed weight gain;

- gastrointestinal symptoms (regurgitation, vomiting, bloating, enlarged liver and spleen).

Herpes

Herpes infection in a newborn is caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (herpes simplex and genital). The highest risk of infection of the fetus is when the mother becomes infected during pregnancy. With an exacerbation of a pre-existing infection, the probability of infection is no more than 5% [1].

Congenital defects are rare and may include hypoplasia (underdevelopment) of the limbs, microcephaly (significant reduction in the size of the skull), retinopathy (damage to the retina), and skin scars.

Clinical manifestations of herpes types 1 and 2 in newborns:

- prematurity;

- pneumonia;

- chorioretinitis (inflammation of the choroid and retina);

- rashes on the skin and mucous membranes;

- jaundice;

- meningoencephalitis (damage to the membranes and substance of the brain).

The most severe herpetic infection occurs when generalized forms occur (disruption of all organs and systems) and when the central nervous system (CNS) is affected. In case of infection during childbirth, the infection appears after 4-20 days (incubation period).

Late complications in children who have had a herpetic infection in utero: recurrent herpetic lesions of the skin and mucous membranes, central nervous system disorders, retardation in psychomotor development, encephalopathy (brain damage).

Chicken pox

If a woman had chickenpox during the period from 8 to 20 weeks of pregnancy, in 30% of cases a miscarriage or stillbirth occurs. Most children who survive develop skeletal malformations and neurological abnormalities [1]. The later the signs of congenital chickenpox appear, the more severe the course: skin rashes, hepatitis, pneumonia, myocarditis, intestinal ulcers. When a rash appears in the first 4 days of life, the disease is not severe.

Late complications in children who have had chickenpox in utero: developmental delay, diabetes mellitus, loss of vision, increased incidence of malignant tumors.

Cytomegalovirus infection

Intrauterine infection with cytomegalovirus is possible if a woman is infected for the first time, as well as if reactivation of a cytomegalovirus infection occurs (transformation of an inactive form of the virus into an active one). Infection during childbirth and breastfeeding is possible.

Congenital defects (if a pregnant woman is infected in the early stages): microcephaly, atresia (absence) of the biliary tract, paraventricular cysts (near the ventricles of the brain), polycystic kidney disease, heart defects, inguinal hernia.

Clinical manifestations of congenital cytomegalovirus infection:

- low birth weight;

- jaundice;

- enlarged liver and spleen;

- rash in the form of hemorrhages on the skin;

- pneumonia;

- chorioretinitis, keratoconjunctivitis (inflammation of the cornea and conjunctiva);

- neurological disorders (meningoencephalitis, cerebral calcifications around the ventricles);

- blood in stool;

- thrombocytopenia (decreased platelet count), anemia;

- severe bacterial infections [14].

Late complications develop, as a rule, after the neonatal period: cerebral palsy, delayed psychomotor development and speech development, difficulties in school, damage to the kidneys, visual and hearing organs [1].

Measles

If you are infected with measles in the early stages of pregnancy, birth defects and miscarriages may develop.

Clinical manifestations in newborns:

- rash - occurs in 30% of children if the woman was sick during childbirth;

- prolonged jaundice;

- increased incidence of pneumonia if immunoglobulin G is not administered.

Parvovirus infection

Congenital defects are not common, but there is a high risk of fetal death if the mother becomes ill in the first half of pregnancy.

Clinical manifestations in newborns:

- fetal edema with severe anemia;

- thrombocytopenia.

ARVI

The most common causes of intrauterine infections are the following infections: adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, RS virus.

Congenital defects occur, but there are no characteristic ones.

Clinical manifestations are noted from the first days of life:

- catarrhal phenomena (swelling, inflammation and redness of the mucous membranes): rhinitis, pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, pneumonia;

- possible increase in body temperature (above 38 °C);

- poor weight gain;

- possible jaundice;

- Bacterial infections are often associated.

Late complications of past infection:

- hydrocephalus (dropsy of the brain) - accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the intracranial spaces, manifested by an increase in the size of the head;

- delayed psychomotor development;

- frequent ARVI;

- glomerulonephritis - damage to the glomeruli of the kidneys (after parainfluenza) [1].

Coxsackie virus

Congenital defects (if infected early): heart and kidney defects.

Clinical manifestations in newborns:

- low birth weight;

- diarrhea;

- rash;

- fever;

- signs of ARVI (nasopharyngitis);

- pneumonia.

Possible late complications of the infection: encephalopathy, myocardial dystrophy (damage to the heart muscle), chronic pyelonephritis [1].

Viral hepatitis B

Congenital defects and diseases: atresia (absence) of the biliary tract, hepatitis.

Clinical manifestations in newborns:

- prematurity;

- low birth weight;

- weight loss;

- diarrhea;

- enlarged belly;

- dark urine;

- discolored stool;

- acute, subacute and chronic hepatitis.

Possible late complications of the infection: delayed psychomotor development, cirrhosis of the liver, liver tumors.

Syphilis

One of the negative trends in recent years is the predominance of cases of congenital syphilis in women diagnosed with early syphilis. Congenital syphilis can be prevented by identifying and treating those infected during pregnancy. Therefore, pregnant women are repeatedly examined for this disease (blood on RW). Early congenital syphilis appears at 2-4 weeks of life, often even later.

Congenital defects: not typical.

Clinical manifestations in newborns:

- A typical triad is: rhinitis (runny nose), pemphigus (rash on the body), enlarged liver and spleen.

- Characterized by poor weight gain, anxiety, causeless shuddering, and central nervous system damage.

Possible late complications: hydrocephalus, encephalopathy [1].

Toxoplasmosis

There is a high probability of infection of the fetus if the infection is “fresh”. If infected in the 1st trimester, the probability is 15%, in the 2nd trimester - 30%, in the last trimester - more than 50%.

Congenital defects: malformations of the eyes (microphthalmia), brain (microcephaly, hydrocephalus), skeleton, heart.

Clinical manifestations in newborns. Three flow options are possible:

- Acute - increased body temperature, enlarged lymph nodes, enlarged liver and spleen, edema, jaundice, diarrhea, skin rash.

- Subacute - the main signs of encephalitis.

- Chronic - hydrocephalus, calcifications in the brain, seizures, blurred vision.

Late complications: encephalopathy with oligophrenia (mental retardation), intracranial hypertension, epilepsy, eye and hearing damage (up to deafness and blindness) [1][3].

Chlamydia

The risk of transmission of infection to an infant at birth from an infected mother is 60-70%. The disease does not appear immediately, but after 5-14 days.

Congenital defects are not common.

Clinical manifestations in newborns:

- purulent conjunctivitis with severe edema;

- nasopharyngitis;

- otitis;

- pneumonia;

- urethritis.

Late complications of a previous infection: frequent and prolonged acute respiratory viral infections.

Rubella

If the mother is infected in the early stages, the pregnancy must be terminated [7]. Infection of a pregnant woman in the first months, especially before 14-16 weeks, leads to spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, and the development of multiple and gross defects in the fetus. Before planning a pregnancy, it is necessary to be examined: if a woman does not have antibodies, then she must be vaccinated against rubella.

Congenital defects: heart defects, eye defects, deafness. These are the main signs of congenital rubella. When infected with rubella during a long period of pregnancy, there may be no congenital heart defect, only damage to the organs of hearing and vision is possible.

Other clinical manifestations:

- prematurity;

- dropsy of the brain (hydrocephalus);

- enlarged liver, spleen;

- thrombocytopenic purpura, etc.

Possible late complications: disability, hydrocephalus, deafness, blindness, retardation in psychomotor and speech development, mental retardation.

Mycoplasmosis

Mycoplasma infection occurs more often during childbirth. When mycoplasmosis is detected in pregnant women, therapy is carried out after the 16th week of pregnancy, which reduces the incidence of morbidity in newborns.

Congenital defects are possible, but there are no characteristic defects for mycoplasma infection.

Clinical manifestations in newborns:

- prematurity;

- pneumonia;

- pale skin;

- respiratory distress syndrome;

- skin rashes (like small hemorrhages);

- meningoencephalitis.

Late complications of the infection: hydrocephalus, encephalopathy [1].

Prevention

Typically, infants receive special vaccinations for preventative purposes. Because the disease has many different forms, sometimes vaccination does not guarantee complete protection against it.

The viral species spreads primarily through airborne droplets.

To avoid infection, you must try to strictly observe the rules of personal hygiene and properly handle food.

When someone in the family is sick with acute respiratory viral infections or acute respiratory infections, the baby must be isolated from the patient.

All relatives, in addition to this, must take Interferon three times a day for a week. All this reduces the risk of infection.

A course of vitamins and minerals will be useful for prevention .

You need to eat exclusively healthy food. It is also important not to get too cold.

If your child does get sick, the first thing to do is consult a doctor. It is this timely measure that will help save the life of a small patient and minimize possible consequences for his health in the future.

Acute purulent meningitis

They can be caused by almost any pathogenic bacterium, but more often by Haemophilus influenzae (48.3%), meningococcus (19.6%) and pneumococcus (13.3%). Group B streptococcus causes meningitis in 3.4%, listeria in 1.9%, and other and unknown microorganisms in 13.5% of cases. Nowadays, the number of patients in whom the causative agent of meningitis is not detected (possibly due to antibiotic therapy before hospitalization) is increasing. Bacteria usually enter the blood from the nasopharynx, followed by bacteremia.

Bacteria can penetrate into the subarachnoid space and ventricles of the brain during septicopyemia or metastasis from infectious foci in the heart and other internal organs. They can also penetrate as a result of contact spread of infection from a septic focus in the bones of the skull, spine, brain parenchyma (sinusitis, osteomyelitis, brain abscess, septic thrombosis of the dural sinuses). The entry points for infection are fractures of the skull bones, paranasal sinuses and mastoid process, as well as areas of neurosurgical intervention. It is extremely rare that infection occurs during lumbar puncture.

Meningococcal meningitis.

The causative agent of the disease is gram-negative diplococcus. The only source of infection is a person – a patient or a bacteria carrier. Of those infected, 10% develop acute meningococcal nasopharyngitis and only in rare cases - meningococcemia, meningitis, or a combination thereof. 70% of people with meningococcal infection are children, especially those attending child care institutions. After entering the body, meningococcus first grows in the upper respiratory tract and can cause rapidly transient nasopharyngitis. In people with immunodeficiency, meningococcus enters the blood, spreads throughout the body, and in severe cases causes meningococcemia with frequent hemorrhagic rash. The resulting endotoxin causes the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (intravascular coagulation syndrome with petechial hemorrhages and thrombosis of small arteries) and endotoxic shock.

The incubation period lasts 2–10 days. The disease begins acutely. Body temperature rises to 38–40°C. A sharp headache occurs, radiating to the neck, back and even to the legs, cerebral vomiting, and meningeal symptoms (in 20% of cases the disease occurs without symptoms of meningitis). With delayed or ineffective therapy, confusion develops (usually delirium), agitation, and then stunned consciousness up to coma. The fundus remains normal. In the blood - neutrophilic leukocytosis, increased ESR (the blood can be normal). After 1–2 days of illness, the pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid increases (up to 200–500 mm of water column), it becomes cloudy, grayish or yellowish-gray. Pleocytosis, predominantly neutrophilic, often reaches 2000–10,000 in 1 ml (the number of lymphocytes is insignificant), the protein content is up to 10–15 g/l, and the glucose content sharply decreases. Meningococci are found in the cells. A hemorrhagic rash in the area of the buttocks, thighs, and legs is characteristic in the form of stars of different sizes and shapes, dense to the touch and protruding above the skin. Petechiae can be on the mucous membranes, conjunctiva, sometimes on the palms, soles (with other infectious meningitis, the rash is much less common).

Of the complications, endotoxic shock is the most dangerous. Endotoxic shock, which most often occurs in children, is characterized by:

1) sudden rise in body temperature, chills;

2) profuse hemorrhagic rash on the skin and mucous membranes, small at first, then increasing, with necrotic areas;

3) the pulse quickens, blood pressure decreases, heart sounds are muffled, breathing is uneven;

4) coma develops, convulsions occur, patients often die without regaining consciousness (due to shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome, as is currently believed);

5) there may be damage to the adrenal glands (previously the death of patients was associated with this).

The duration of the disease with adequate treatment is 2–6 weeks. Hypertoxic forms are possible, leading to death within 24 hours. Severe forms of the disease can be complicated by pneumonia, myocarditis, pericarditis

Meningitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae.

The causative agent is gram-negative Pfeiffer-Afanasyev bacilli, the most dangerous serotype is b-Hib. The source of infection is only humans. Nowadays, such meningitis accounts for 50% of all cases of purulent meningitis. Mostly newborns and young children are affected (90% of patients are under 6 years of age). In young children, meningitis is usually primary; in adults, it usually occurs as a result of acute sinusitis, mezootitis, and skull fractures. The development of the disease can be facilitated by cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, splenectomy, hypogammaglobulinemia, diabetes mellitus, and alcoholism. The disease increases in spring and autumn and decreases in summer. Pathomorphology, clinical picture and changes in the cerebrospinal fluid are similar to other acute purulent meningitis. Haemophilus influenzae can be isolated both from the cerebrospinal fluid and from the blood (from the blood often already at the onset of the disease).

The duration of the disease is from 10 to 20 days. There are fulminant forms, but sometimes the disease drags on for weeks or months. In children with this meningitis, the initial symptom may be ataxia. Subdural effusion and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion often occur in children.

More often than with other purulent meningitis, stupor and coma develop. Without treatment, paralysis of the external eye muscles, deafness, blindness, hemiplegia, seizures, mental retardation, and dementia often develop. In untreated cases, neonatal mortality reaches 90%; in adults, the prognosis is more favorable, spontaneous recovery is possible. With adequate therapy, mortality reaches, however, 10%, and complications are common.

Pneumococcal meningitis.

Pneumococcus (Streptococcus pneumoniae) is now very widespread, as is meningococcus. Meningitis often develops against the background of pneumonia (25%), mezootitis or mastoiditis (30%), sinusitis (10–15%), often in patients with head injury and cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Alcoholism, poor nutrition, diabetes mellitus, multiple myeloma, hypogammaglobulinemia, hemodialysis, organ transplantation, splenectomy (the disease is especially severe in this case), long-term corticosteroid therapy and other causes of immunodeficiency predispose to it. More than 50% of patients are under 1 year of age or over 50 years of age.

The onset of the disease is acute with the development of confusion and/or depression of consciousness, less often – gradual, against the background of a respiratory infection. Body temperature can be high, low-grade, even normal. Characterized by a more frequent development of stupor, coma, epileptic seizures, damage to cranial nerves, focal neurological symptoms (especially hemiparesis, paresis of horizontal gaze). Possible acute swelling of the brain with herniation. Due to increased ICP, there may be congestion of the optic discs. On the 3rd–4th day of illness, rashes appear on the mucous membrane of the mouth, less often on the arms and torso, and occasionally a small hemorrhagic rash.

There are bradycardia, decreased blood pressure, pronounced changes in the blood, in the cerebrospinal fluid - neutrophilic pleocytosis of more than 1000 in 1 μl, hypoglycorachia. In cases of fulminant course, the cytosis is much less (non-purulent bacterial meningitis); without treatment, patients die on the 5th–6th day. The disease can take a protracted course. Mortality now reaches an average of 20–30%, in older people – 40%. Mortality is especially high if meningitis occurs due to pneumonia, empyema, lung abscess, or persistent bacteremia caused by bacterial endocarditis. Mortality is exceptionally high in the case of the “Austrian syndrome,” which includes pneumococcal meningitis, pneumonia and bacterial endocarditis.

The diagnosis is confirmed by the detection of pneumococcus in the cerebrospinal fluid or blood, and positive serological reactions.

Listeria meningitis.

The causative agent of the disease is Listeria monocitogenes, an aerobe, zoonotic gram-positive coccobacterium that does not form capsules and spores (serotypes 1a, 1b, 1vb). The disease develops mainly in young children, especially newborns, and in elderly people with tumors, against the background of immunosuppressive therapy. Males get sick twice as often. Spring-summer-autumn seasonality is typical. The main route of infection is nutritional.

The incubation period is 1–4 days. The disease begins acutely or subacutely. General cerebral and meningeal symptoms appear against the background of signs of intoxication, pain when swallowing, erythematous rash, characteristic rashes on the face (butterfly-shaped), gastroenteritis, hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice. Body temperature rises to 38–40°C and can persist for up to 30–50 days. Confusion, stunned consciousness, and respiratory distress syndrome often occur, which most often indicates the development of meningoencephalitis. Unlike other meningitis, stiffness of the neck muscles is often absent. Cytosis in the cerebrospinal fluid is often lymphocytic, ranging from 50 to 100 in 1 μl, the protein content is slightly increased, the glucose content is normal or slightly reduced. Verification of the pathogen is carried out by isolating Listeria from cerebrospinal fluid, throat swabs, and amniotic fluid. With adequate treatment, the prognosis is favorable in most cases.

Staphylococcal and streptococcal meningitis.

Usually these are secondary meningitis, developing at any age, in particular in newborns and children in the first months of life. The infection penetrates into the meninges hematogenously (in acute staphylococcal or streptococcal endocarditis, boils, carbuncles, umbilical sepsis) or by contact (in the presence of osteomyelitis, epiduritis, purulent otitis, sinusitis).

The onset of the disease is acute, often against the background of septicopyemia. Intense headaches on the 2nd–3rd day are accompanied by meningeal symptoms, tremors, convulsions, disturbances of consciousness, and an inflammatory picture of the blood. Their combination with signs of ICP and intoxication forms the core of the clinical picture. Often the cranial nerves are involved in the process, and signs of pyramidal insufficiency occur. The formation of numerous microabscesses of the brain and the frequent addition of a fungal infection are characteristic. Mortality in the acute period is 20–60%.

With a lumbar puncture, liquor flows out under very high pressure; it is cloudy, gray, with a greenish tint. Neutrophilic pleocytosis - from several hundred to 3000 in 1 μl, protein content - 2-6 g/l, glucose and chlorides - reduced. The diagnosis is based on medical history, clinical examination and laboratory results of cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Recurrent bacterial meningitis.

Recurrent episodes of bacterial meningitis indicate an anatomical defect and/or immunodeficiency. Relapses are also often observed after TBI, while the first attack of meningitis can occur much later, several years later. As a rule, the causative agent of the disease is pneumococcus. It can penetrate into the subarachnoid space through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, the site of a fracture of the bones of the base of the skull, the eroded bone surface of the mastoid process, as well as during penetrating head wounds or neurosurgical interventions. Often there is liquor rhinorrhea or otorrhea, which can be transient (liquor rhinorrhea reveals itself as a significant concentration of glucose in the secretions from the nose and ear, it is often mistakenly regarded as rhinitis). The “old” sign of liquorrhea is the “teapot” symptom: when the head is tilted, the flow from the nose intensifies. A radical solution to the problem of recurrent meningitis is surgical closure of the cerebrospinal fluid fistula.

Meningitis caused by fungi.

Usually caused by a combined fungal-bacterial or fungal-viral infection. The most common fungi are Candida, Aspergillus, and Rhodotorula, which are widespread facultative opportunistic anaerobes. During pregnancy, placentitis and intrauterine infection of the fetus may develop. Candidiasis of the central nervous system, including meningitis, develops in 60% of cases in newborns and children in the first year of life.

The development of the disease occurs when immunity is impaired, in particular the suppression of local immune reactions of the capillary endothelium, ependyma, glia, leading to an increase in the permeability of the blood-brain barrier. Risk factors are intrauterine infection, prematurity, perinatal encephalopathy, resuscitation measures (catheterization, prolonged mechanical ventilation, etc.), acute bacterial and viral infections, their treatment with large doses of antibiotics and hormones. Candidal meningitis can occur against the background of candidal sepsis, osteomyelitis of tubular bones, and arthritis.

The clinical picture is dominated by general toxic-infectious symptoms. Neurological symptoms are nonspecific, they are represented by increasing general anxiety, motor agitation and/or lethargy, shuddering, refusal to eat, vomiting, throwing back the head, hydrocephalus (bulging fontanelles, divergence of the skull bones, dilation of the veins of the integumentary tissues of the head, congestive optic discs, etc. ), fever or low-grade fever (temperature may be normal). Focal neurological symptoms, disturbances of consciousness, signs of decortication, and decerebration are possible. Diagnosis of the disease is facilitated by the presence of thrush, glossitis, and skin enanthems in the child. The diagnosis is confirmed by detection of fungi by microscopy of blood and cerebrospinal fluid, diagnostic antibody titers and determination of fungal antigen in cerebrospinal fluid, blood, urine, and stool. In the cerebrospinal fluid, neutrophilic pleocytosis is observed up to 1–2 thousand cells in 1 μl, an increase in protein up to 1–3 g/l.

The course of the process can be protracted and recurrent. Inflammatory changes in the blood, neutrophilia or neutropenia, signs of immunodeficiency, lack of effect from antibiotic treatment and a positive effect from the administration of fluconazole (Diflucan) already on the 2-5th day of treatment are common. Ancotil (mycocyvin) and amphotericin B (fungizone) are also effective.

Cryptococcal (torulose) meningitis and meningoencephalitis.

The causative agent of the disease is the common saccharomycete Torula histolytica, the carriage of which is almost universal in humans. Infection occurs through the respiratory tract. People of any age get sick, which is facilitated by immunodeficiency, often AIDS. The membranes of the brain are affected, especially the base of the brain; the fungus can accumulate in the perivascular spaces and ventricles of the brain.

The disease begins acutely with an increase in body temperature to 37.5–38°C, the appearance of a severe headache, vomiting, and meningeal syndrome. On days 2–5, drowsiness and damage to the cranial nerves (ptosis, diplopia, strabismus, deafness, etc.) develop, and congestive optic discs are detected. The course of the disease is chronic and progressive. During a lumbar puncture, cerebrospinal fluid flows out under high pressure, it is opalescent and may be cloudy. Lymphocytic pleocytosis (50–2000 cells in 1 μl), increased protein content (up to 4–7 g/l), and in most cases a decrease in glucose levels are detected. In the blood - moderate neutrophilic leukocytosis, lymphopenia. Over time, signs of hydrocephalus, cachexia, increasing signs of intracranial hypertension and general intoxication appear.

The diagnosis is based on the history, clinical picture and laboratory tests. The diagnosis is confirmed by the detection of yeast fungi in the cerebrospinal fluid and their detection during its sowing. Treatment includes intravenous drip administration of amphotericin B (fungisone) 250 mcg/kg once a day or every other day for 4–8 weeks, sulfonamides, dehydration, and the administration of vasoactive and metabolic drugs. The prognosis is unfavorable, the outcome is always fatal

Complications of acute purulent meningitis.

Occur on average in 10–30% of patients, more often in young children and the elderly.

Early complications include increased ICP, epileptic seizures, arterial and/or venous thrombosis, subdural effusion, hydrocephalus, and cranial nerve damage.