Paroxysmal disorders of consciousness in neurology are a pathological syndrome that occurs as a result of the course of the disease or the body’s reaction to an external stimulus. Disorders manifest themselves in the form of attacks (paroxysms) of various types. Paroxysmal disorders include migraine attacks, panic attacks, fainting, dizziness, epileptic seizures with and without convulsions.

Neurologists at the Yusupov Hospital have extensive experience in treating paroxysmal conditions. Doctors know modern effective methods for treating neurological pathologies.

Disorder of consciousness

Paroxysmal disorder of consciousness manifests itself in the form of neurological attacks. It can occur against the background of apparent health or during an exacerbation of a chronic disease. Often, paroxysmal disorder is recorded during the course of a disease that is not initially associated with the nervous system.

The paroxysmal state is characterized by the short duration of the attack and the tendency to recur. The disorder has different symptoms, depending on the provoking condition. Paroxysmal disorder of consciousness can manifest itself as:

- epileptic seizure,

- fainting,

- sleep disorder,

- panic attack,

- paroxysmal headache.

The causes of the development of paroxysmal conditions can be congenital pathologies, injuries (including at birth), chronic diseases, infections, and poisoning. Patients with paroxysmal disorders often have a hereditary predisposition to such conditions. Social conditions and harmful working conditions can also cause the development of pathology. Paroxysmal disorders of consciousness can cause:

- bad habits (alcoholism, smoking, drug addiction);

- stressful situations (especially when they are repeated frequently);

- disturbance of sleep and wakefulness;

- heavy physical activity;

- prolonged exposure to loud noise or bright light;

- unfavorable environmental conditions;

- toxins;

- sudden change in climatic conditions.

Causes

Symptoms of paroxysmal tachycardia of this type look as follows. The patient experiences bouts of rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath and chest pain. He also experiences general weakness and deterioration in health. If the disease is caused by malfunctions in the nervous system, then a person may experience increased blood pressure, a feeling of cold and a lump in the throat.

The correct diagnosis can be made by listening to the patient. This is done to determine the frequency of contractions of his heart muscle. The type of disease can be determined using an electrocardiogram.

Paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia occurs if the source of generation of rapid electrical impulses originates in the ventricle or interventricular wall. This type of disease is dangerous because it can develop into ventricular fibrillation.

In this case, not all the muscle tissue of the ventricles, but its individual fibers, is subjected to random contraction. As a result, the dynamics of the heart muscle are disrupted, because the phases of systole and diastole are absent as such.

How does paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia threaten a person? Extremely unpleasant symptoms and dangerous consequences: the occurrence of severe disturbances in the functioning of the blood supply system to organs and tissues, shock, pulmonary edema.

What causes ventricular tachycardia and what are the causes of its occurrence? Factors provoking the disease are the following:

- coronary heart disease in all forms (acute or chronic);

- cardiomyopathy; inflammatory processes in the heart muscle; vices of varying degrees of complexity;

- Unexplained causes provoke heart muscle disease in 2% of patients.

Epilepsy disorders

In epilepsy, paroxysmal conditions can manifest themselves in the form of convulsive seizures, absence seizures and trances (non-convulsive paroxysms). Before a grand mal seizure occurs, many patients feel a certain type of warning sign - the so-called aura. There may be auditory, auditory and visual hallucinations. Someone hears a characteristic ringing or feels a certain smell, feels a tingling or tickling sensation. Convulsive paroxysms in epilepsy last several minutes and may be accompanied by loss of consciousness, temporary cessation of breathing, involuntary defecation and urination.

Nonconvulsive paroxysms occur suddenly, without warning. With absence seizures, a person suddenly stops moving, his gaze is directed ahead, he does not react to external stimuli. The attack does not last long, after which mental activity returns to normal. The attack goes unnoticed by the patient. Absence seizures are characterized by a high frequency of attacks: they can be repeated tens or even hundreds of times per day.

Causes of autonomic dystonia syndrome

Autonomic dystonia syndrome is classified as a consequence of various pathologies of the central and peripheral nervous system. VDS is not an independent disease and rarely occurs overnight. The causes of vegetative dystonia syndrome are as follows:

- Problems at home, at school, which lead to systematic constant stress;

- Brain damage due to problems during pregnancy;

- Hormonal changes in adolescence (adolescence);

- Heredity, expressed by poor tolerance to work, high meteotropicity, and so on;

- Diseases of the endocrine system (diabetes mellitus, etc.);

- Bronchial asthma, stomach ulcer, hypertension and other somatic pathologies;

- Passive lifestyle;

- Systematic diseases of the nervous system;

- Carious teeth, sinusitis, otitis media and other permanent foci of infection;

- Mental and physical overload;

- Persistent autoimmune diseases.

Panic disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety)

Panic disorder is a mental disorder in which the patient experiences spontaneous panic attacks. Panic disorder is also called episodic paroxysmal anxiety disorder. Panic attacks can occur from several times a day to once or twice a year, while the person is constantly expecting them. Severe anxiety attacks are unpredictable because their occurrence does not depend on the situation or circumstances.

This condition can significantly impair a person's quality of life. The feeling of panic can be repeated several times a day and last for an hour. Paroxysmal anxiety can occur suddenly and cannot be controlled. As a result, a person will feel discomfort while in society.

Symptoms of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia

Paroxysmal tachycardia always has a sudden, distinct onset. The patient feels a push or compression, and sometimes a prick, in the area of the heart.

The attack may be accompanied by symptoms:

- dizziness;

- noise in the head;

- lightheadedness or fainting;

- sweating;

- nausea;

- trembling in the body.

To correctly diagnose tachycardia, it is important to conduct a thorough interview and examination of the patient. Highly qualified doctors of the Cardiology Center of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency will be able to quickly identify the disease.

Sleep disorders

The manifestations of paroxysmal sleep disorders are very diverse. These may include:

- nightmares;

- talking and screaming in sleep;

- sleepwalking;

- motor activity;

- night cramps;

- shuddering when falling asleep.

Paroxysmal sleep disorders do not allow the patient to regain strength or rest properly. After waking up, a person may feel headaches, fatigue and weakness. Sleep disorders are common in patients with epilepsy. People with this diagnosis often have realistic, vivid nightmares in which they run somewhere or fall from a height. During nightmares, your heart rate may increase and you may perspire. Such dreams are usually remembered and can be repeated over time. In some cases, during sleep disorders, breathing disturbance occurs; a person may hold his breath for a long period of time, and there may be erratic movements of the arms and legs.

Diagnostics

Tachycardia can be sinus and paroxysmal; they differ from the location of the electrical impulse that causes the heart to contract. To make a diagnosis, the doctor of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency performs a physical examination, collects anamnesis and prescribes tests.

Physical examination includes:

- external examination of the patient;

- heart rate measurement;

- blood pressure measurement.

Instrumental research:

- ECG;

- ECG with additional load on the body;

- daily ECG monitoring;

- ECHO;

- stress echocardiography;

- MRI;

- CT cardiography.

Treatment

To treat paroxysmal conditions, consultation with a neurologist is necessary. Before prescribing treatment, the neurologist must know exactly the type of attacks and their cause. To diagnose the condition, the doctor clarifies the patient’s medical history: when the first episodes of attacks began, under what circumstances, what their nature is, and whether there are any concomitant diseases. Next, you need to undergo instrumental studies, which may include EEG, EEG video monitoring, MRI of the brain and others.

After performing an in-depth examination and clarifying the diagnosis, the neurologist selects treatment strictly individually for each patient. Therapy for paroxysmal conditions consists of medications in certain doses. Often the dosage and the drugs themselves are selected gradually until the required therapeutic effect is achieved.

Typically, treatment of paroxysmal conditions takes a long period of time. The patient should be constantly monitored by a neurologist for timely adjustment of therapy if necessary. The doctor monitors the patient’s condition, assesses the tolerability of the drugs and the severity of adverse reactions (if any).

The Yusupov Hospital has a staff of professional neurologists who have extensive experience in treating paroxysmal conditions. Doctors are proficient in modern effective methods of treating neurological pathologies, which allows them to achieve great results. The Yusupov Hospital performs diagnostics of any complexity. Using high-tech equipment, which facilitates the timely start of treatment and significantly reduces the risk of complications and negative consequences.

The clinic is located near the center of Moscow and receives patients around the clock. You can make an appointment and get advice from specialists by calling the Yusupov Hospital.

Paroxysmal dyskinesias: differential diagnosis with epilepsies

Paroxysmal dyskinesias are neurological conditions with a varied clinical picture, characterized by sudden attacks of pathological involuntary motor activity (i.e., accompanied by attacks of hyperkinesis) in the muscles of the limbs, trunk, face, and neck [3]. We call attacks of hyperkinesis here “attacks of hyperkinesis” so as not to confuse them with the term “epileptic seizures.”

The relevance of the term “paroxysmal” is due to the fact that hyperkinesis suddenly appears and also suddenly disappears, taking the form of attacks. Between attacks of hyperkinesis, the motor sphere and human behavior as a whole remain completely normal. Hyperkinesis attacks may manifest as involuntary, rapid, irregular jerks (chorea); slow snake-like or worm-like movements, smoothly flowing from one muscle to another (athetosis); increased muscle tone with repeated twisting movements and pathological postures (dystonia); uncontrolled circular movements in one or more limbs (ballism) or any combination of these hyperkinesis.

Paroxysmal dyskinesias are divided into paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD) and paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia (PNKD). Hyperkinesis attacks in PCD develop as a result of provoking factors (triggers) that act unexpectedly and suddenly. In contrast, in PNCD, attacks occur spontaneously at rest or interrupt daily physical activity; their severity is enhanced by alcohol, coffee, stress, violent emotions, etc. [1]. Separately, there are two types of paroxysmal dyskinesias: those provoked by prolonged or excessive physical activity (PKFN) and those provoked by sleep (hypnogenic dyskinesia - PHD).

Paroxysmal dyskinesias are characterized depending on the duration of the attacks (attacks can be short-lived - less than 5 minutes or long-lasting - more than 5 minutes), can be familial in nature, develop due to unclear reasons (sporadic forms) or secondary, against the background of any disease (symptomatic forms) .

PCD was previously called paroxysmal choreoathetosis, but the modern term is more correct, since with PCD not only choreoathetosis develops, but also other types of hyperkinesis. In many patients with PCD, the disease is idiopathic (i.e., familial or sporadic), with symptoms manifesting up to 20 years, and most often before 10 years. In general, the age of onset varies from 6 months to 40 years. According to the literature, boys are affected more often than girls, but the exact prevalence is unknown due to the fact that the disease is extremely rare.

Transient attacks of hyperkinesis in PCD in the early stages affect the muscles of the arms and legs, but as the disease progresses, hyperkinesis also affects the muscles of the face, neck and torso. Attacks can be unilateral or bilateral, but their characteristic feature is their asymmetry, even if they are bilateral. Involuntary contraction of the facial or oromandibular muscles results in grimacing, slurred speech (dysarthria), and even mutism. Attacks are never accompanied by a change in consciousness. Hyperkinesis occurring in the legs or trunk leads to sudden falls and often multiple injuries. In addition to sudden motor attacks, automatisms appear - yawning, shortness of breath, echolalia, echopraxia. Attacks become more frequent under the influence of external factors.

Most patients with PCD experience attacks during the day. Their frequency varies - from 1 per month or several months to 100 daily. At the beginning of each attack, some patients experience precursor sensations (tingling, burning and other paresthesias; dizziness; muscle spasms). After this, as a rule, hyperkinesis develops in the same area of the body.

The frequency of attacks in PCD decreases with age. Most patients with PCD have short attacks, ranging from a few seconds to 5 minutes. Less commonly, hyperkinesis attacks last several hours. PKD with prolonged and infrequent attacks make their debut at a later age. The duration of attacks may vary. Let's give an example.

Girl, P.K., 6 years old. Diagnosis: autosomal recessive rolandic epilepsy. Paroxysmal dyskinesia. Complaints: paroxysms of hyperkinesis in the left limbs and left half of the face. Life history: heredity is burdened: on the mother’s side (grandmother has three twins, prematurity, miscarriages). A child from the first pregnancy, which occurred against the background of the threat of early miscarriage, at 4 months - bleeding (inpatient treatment), against the background of repeated acute respiratory viral infections (ARVI); first urgent rapid birth. She screamed immediately. Discharged on the 7th day. Breastfed for up to 1.5 months. I was gaining weight well. Psychomotor development: holds head - by 3 months, sits - by 7 months, walks - by 11 months. He speaks according to his age.

History of the disease: at the age of 1 year, twitching of the left leg (non-synchronous, sometimes rotational movements) appeared on each awakening; after 2-3 months, twitching began to appear simultaneously in the leg and arm; after a few months, twitching in the face on the same side appeared. At 1.5 years old, she was diagnosed with episyndrome, left-sided Jacksonian convulsions. Gluferal was prescribed, then convulsofin, depakine, benzonal in the form of mono- and polytherapy (up to three drugs at the same time) - without effect. During treatment, the frequency of attacks remained from 1 to 15 per day, they occurred not only upon awakening, but also during wakefulness (when provoked by emotional and physical stress); during sleep in the drowsiness phase, before waking up. Maximum duration up to 30 s. She did not lose consciousness. Anticipates attacks.

The neurological status revealed no focal symptoms.

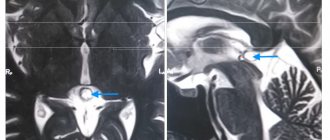

Video electroencephalography (video-EEG): background EEG with eyes closed in the occipital regions is represented by hypersynchronous alpha activity, amplitude 150–200 μV, frequency 8 Hz. When carrying out photostimulation with a frequency of 18 Hz, generalized bursts of peak-wave complexes are observed, not accompanied by clinical patterns of an epileptic seizure. Flash duration is 1–3 s. Sleep EEG recorded stages 1–3 of sleep. In stages 1–2, two-phase sharp waves are recorded, localized in the central region with amplitude predominance on the right. Generalized outbreaks of an epileptic nature, not accompanied by clinical manifestations, have also been recorded during sleep. Upon awakening and while awake, two episodes of movements in the left hand in the form of choreoathetosis were recorded. The motor phenomenon upon awakening was not accompanied by changes in bioelectrical activity (BEA). The second phenomenon coincided with an outbreak of generalized epileptic activity. Conclusion: video-EEG monitoring revealed two types of pathological activity: 1) local changes in the central region, which may be characteristic of rolandic epilepsy; 2) generalized epileptic activity. The motor phenomena were of the nature of hyperkinesis (choreoathetosis) and are probably not epileptic seizures.

Examination results: biochemical blood test, electrocardiogram (ECG), ultrasound examination of internal organs: without features. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain - without pathology. Ophthalmologist: no change. Psychologist: psychological development corresponds to the age norm. She was examined in the laboratory of hereditary metabolic diseases of the Medical Genetic Center of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences: GM1 gangliosidosis, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis 1 and 2, mitochondrial diseases, Wilson-Konovalov disease were excluded.

Upon discontinuation of anticonvulsant therapy (carbamazepine, barbiturates), there was no change in the frequency of attacks. Introduced by the staff. Attacks of choreoathetosis in the left extremities persisted with a frequency of 5–11 times a day, during the day and at night, and were periodically associated with movements and emotional stress (Table 1). After discharge, the frequency of attacks decreased. After 6 months, therapy was adjusted (increasing the dose of Nakoma, Frisium), and the attacks stopped. There were no attacks for 1 month, then they resumed again, mainly in the morning, in connection with awakening, and less often during wakefulness.

| Table 1. Diary of episodes for one day |

EEG during follow-up therapy: positive dynamics are noted in the form of a decrease in the prevalence of diffuse epileptiform discharges, a decrease in the amplitude of regional central-vertex discharges, as well as their decrease during wakefulness.

PNCD. The former name is “paroxysmal dystonic choreoathetosis”. PNCD often manifests before the age of 20, but the age of onset is extremely variable. Boys get sick more often. Attacks are characterized by the presence of any hyperkinesis (chorea, athetosis, dystonia, ballisma). It must be emphasized that they are never accompanied by impaired consciousness. The attacks can be so severe that they cause a sudden fall or disruption of gait and other types of motor activity, causing the severity of the disease. Attacks in PNCD develop suddenly, without any specific triggers, which distinguishes them from PCD. The severity of attacks can be aggravated by fear, anxiety, excitement, joy, cooling or overheating, drinking alcohol, coffee, tea, chocolate, etc. The frequency of attacks with PNCD is much less frequent than with PCD, 2–3 times a month; however, they sometimes develop more than 100 times a day. Attacks are preceded by precursors in the form of unusual sensations (tingling, spreading warmth, etc.), muscle tension. Attacks during PNCD last from 5 minutes to several days. Based on their duration, they are divided into short (less than 5 minutes) and long (more than 5 minutes). With age, the duration of attacks gradually decreases.

PKFN is a rare form of paroxysmal dyskinesia in which attacks are provoked by prolonged or excessive physical activity (formerly known as “intermediate paroxysmal dyskinesia”).

In patients with the idiopathic (familial or sporadic) form, the disease debuts in childhood. Only in secondary (symptomatic) forms does the age of onset increase to 30 years. Girls get sick more often.

PKFN is characterized primarily by sudden transient dystonic attacks, manifested by involuntary repeated muscle contractions with the formation of pathological postures (often painful). In some patients, attacks of dystonia manifest as choreoathetosis. Attacks occur against the background of strong or prolonged physical activity (running, walking long distances), sometimes PKFN is provoked by passive movements in the affected limbs, and intensifies under the influence of external factors. Attacks mainly occur in the legs, but sometimes, especially during prolonged episodes, the muscles of the face, neck, and torso are involved. As a rule, symmetrical parts of the body are affected (bilateral attacks), but there are also asymmetrical ones. No precursor sensations were noted during PKFN. The frequency of attacks is 1–5 per month. Cases have been described where attacks occur 1–2 times a day. The duration of attacks is from 5 to 30 minutes, less often less than 2 minutes. The duration of attacks decreases with age; in general, they last from a few seconds (in adults) to several days (in children). Let's give a second example.

Girl, K.D., 9 years old. Diagnosis: paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. Symptomatic epilepsy. Cerebral palsy (CP), spastic-hyperkinetic form. Complaints: lag in psychomotor development, periodic attacks of worm-like violent movements, lasting from several hours to days. Life history: child from young healthy parents, first premature birth at 36 weeks. At birth, weight is 3.0 kg, height is 50 cm. Development with delayed psychomotor skills. At 8 months, a diagnosis of cerebral palsy was made. Systematically receives rehabilitation therapy. Heredity is not burdened.

History of the disease: at the age of 7 years, against the background of acute respiratory viral infection, the first attack of hyperkinesis developed in the form of choreoathetosis, which lasted 3 days. Due to the severity of the condition (respiratory arrhythmia, ongoing hyperkinesis), the child was in the intensive care unit. During therapy (tizercin, finlepsin, depakine, cyclodol), hyperkinesis began to weaken by the end of 3 days and then stopped. Motor activity was completely restored. After 2-3 weeks - a repeated attack of choreoathetosis, lasting about 10 minutes, less severe, without loss of consciousness. Then hyperkinesis attacks, lasting several hours, were repeated once a month.

Neurological status: mild divergent strabismus, weak convergence on the left. Tongue deviation to the right. The gait is spastic-paretic with propulsion. Hemiatrophy of the extremities on the right. Muscle tone is increased according to the spastic type, with elements of plasticity. Tendon and periosteal reflexes are increased with expansion of the zones, more pronounced on the right. Bilateral foot clonus. Pathological foot reflexes on both sides. The severity of the condition has not been studied in the Romberg position. Coordinator tests are performed with intention and dysmetry on the left. No sensitivity disorders were identified. Dystonic attacks in response to emotional or physical provocation.

Survey results. ECG: without pathology. Biochemical blood test: no pathology. Ophthalmologist: anterior segment, refractive media, fundus - no changes. Neuropsychologist: deficit in the kinesthetic organization of movements and speech, as well as modality-specific impairments of auditory-verbal memory and weakness of objective visual gnosis. EEG monitoring of daytime sleep: in the left central-parietal region, single monophasic sharp waves are recorded, with a frequency of 1–2 per second, followed by a period of increased sharp waves up to 5 per second and the appearance of individual “peak-wave” complexes in their series. Taking into account the examination data, the attacks were regarded as attacks of symptomatic epilepsy; Depakine (600 mg/day) was prescribed. With Depakine, there was a complete absence of attacks for 6 months. Against the background of acute nasopharyngitis, hyperkinesis appeared, increasing in intensity, frequency and amplitude over 2 days. The administration of diazepam, then aminazine, did not allow us to control the attacks of hyperkinesis, which were repeated every 5–10 minutes and were of a “status” nature, and therefore the child was transferred to the intensive care unit. In the intensive care unit, due to intractable dystonic attacks (ballism, choreoathetosis), a decision was made to administer thiopental, muscle relaxants, and artificial pulmonary ventilation (ALV) for life-saving reasons. The course of ARVI was complicated by the phenomena of upper lobe pneumonia. During intravenous administration of tiapridal at a dose of 300 mg/day, dystonic attacks persisted for 5 days. On the 6th day, chlorpromazine 1.0 ml was administered intravenously. The hyperkinesis continued. Intravenous administration of depakine, diazepam, and sodium hydroxybutyrate stopped hyperkinesis for a short time. On days 8–10, pulse therapy with methylprednisolone was administered at a dose of 400 mg/day without effect. On the 11th day, we applied 1/8 tablet of nacom (in the morning). Treatment for 4 days without effect. On the 15th day, clonazepam was prescribed orally - up to 1.5 mg/day, Topamax - 50 mg/day, Finlepsin - 300 mg/day - without effect. After temporary cessation of thiopental infusions for 2 hours, choreoathetosis persisted. The child was conscious and responded to examination. It was not possible to stop the thiopental infusion. On the 15th day, to tiapridal at a dose of 600 mg/day, obzidan was added at a dose of 0.5 mg/day (in saline solution 20.0 - through an infusion pump), the next day the dose of obzidan was adjusted - 0.7 mg/day in saline solution 20.0 (1 ml/h) with a clear positive effect in the form of a decrease in hyperkinesis, the appearance of “light spaces”. On the 17th day, only constant myoclonus of the limbs and shoulder girdle persisted. The dose of obzidan was increased to 1 mg/day. EEG monitoring in the intensive care unit: diffuse functional-organic disorders of the BEA of the brain. There is no data indicating the presence of regional, generalized, diffuse epileptiform activity. Numerous myoclonus recorded during the study, taking into account clinical and electroencephalographic correlates, was regarded as myoclonus of non-epileptic origin. As a result of MRI of the brain, the following were revealed: basal-temporal atrophy on the left, secondary expansion of the basal subarachnoid spaces in this area to the degree of a cyst; diffuse cortical-subcortical subatrophy, realized by diffuse expansion of the subarachnoid spaces of the convexital sections of the cortex and reactive asymmetric, predominantly right-sided expansion of the lateral ventricles. Examined by a geneticist: GM1- and GM2-gangliosidoses, NARP (neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa), organic aciduria and aminoacidopathy, mitochondrial diseases, Wilson-Konovalov disease, Hallevorden-Spatz disease were excluded. During therapy (thiopridal, obzidan, depakine), thiopental anesthesia was stopped, and hyperkinesis was reduced. In total, the duration of the attack was 17 days. In a stable condition, the patient was transferred from intensive care to the psychoneurology department, where she received depakine - 600 mg/day, anaprilin - 10 mg/day, nootropil - 600 mg 2 times a day, tiapridal - 100 mg/day. Against the background of a single reduction in the dose of tiapridal to 3.3 mg in the morning, an increase in hyperkinesis was noted. By the time of discharge from the hospital, the child’s neurological status did not differ from the state upon admission. Minor dystonic attacks to provocation persisted. The follow-up period was 3 years.

PGD is a rare variant of the disease characterized by transient attacks of involuntary movements during NREM (non-REM) sleep. Occasionally, PGD attacks are preceded by specific precursor sensations. Attacks are often associated with periods of awakening (arousal); occur during sleep, while the patient’s eyes are open, and hyperkinesis occurs in the limbs and torso. Sometimes attacks are accompanied by vocalizations, respiratory rhythm disturbances, and tachycardia. Then normal sleep continues, the attacks themselves are completely amnesiac. The severity of attacks is aggravated by external factors [4].

Idiopathic variants make their debut in childhood, with familial forms earlier than sporadic ones. The age of onset varies from 2 to 23 years for familial cases and from 3 to 47 years for sporadic cases. The frequency of attacks is usually 4–5 times per year, but sometimes it increases to 4–5 times per night. Attacks are usually short - from 20–50 s to 2 minutes.

Some patients, along with nocturnal attacks, experience attacks during wakefulness, kinesigenic or non-kinesigenic. In addition, with familial variants, different family members may experience different forms of paroxysmal dyskinesia. Let's give another example.

Child, I.O., 6 years old. Diagnosis: cerebral palsy, left-sided hemiparesis. Rolandic epilepsy. Paroxysmal dyskinesia. Upon admission, complaints about episodes of “stretching” during sleep when changing body position (tonic tension in the muscles of the neck and back, followed by extension of the torso and throwing back of the head). Paroxysms are accompanied by cessation of breathing, vegetative symptoms in the form of cold skin, and opercular automatisms (smacking). In the morning hours after night paroxysms, he is lethargic, awkward, and stumbles. The frequency of paroxysms is once a month.

From the anamnesis: the parents are healthy, there is no heredity. A child from the 4th pregnancy, characterized by a pathological course (against the background of chronic sinusitis, otitis, threat of miscarriage with placental abruption in the second trimester, hypothyroidism, Rh conflict), with hospital treatment (hormonal drugs); second premature birth

34 weeks by emergency caesarean section. Birth weight 2.7 kg, height 52 cm. The child was born in severe asphyxia, was on a ventilator for 7 days, and suffered from pneumonia. Due to hemolytic disease of newborns, a single replacement blood transfusion was performed. According to neurosonography, during the neonatal period, hemorrhage was observed in the lateral ventricles of the brain, resulting in periventricular leukomalacia. She has been seen by a neurologist since birth. From the age of 2 years, nocturnal attacks are observed in the form of abdominal pain, the urge to defecate, accompanied by facial distortion and opercular movements for half an hour, followed by post-attack sleep. From the age of 3 years, the seizures changed (simple focal motor seizures in the form of clonic convulsions in the left upper limb lasting 15 minutes followed by sleep). Finlepsin retard was prescribed - 300 mg/day, after which night “sipping” appeared when changing body position during sleep. With the introduction and increase in the dose of Depakine Chrono to 1000 mg/day, “sipping” became less frequent. Due to the development of thrombocytopenia, the dose of depakine chrono was reduced to 750 mg/day and the dose of finlepsin was increased to 400 mg/day. At the age of 4, against the background of herpetic stomatitis, generalized tonic-clonic seizures with loss of consciousness developed, the frequency of attacks was 5 times per night.

Neurological status: Convergent strabismus. Muscle tone is increased according to the spastic type, tendon reflexes are high - S > D, pathological foot symptoms. Muscle wasting in the left extremities, more in the leg. Flat valgus placement of the left foot, retraction in the left ankle joint. Retraction in the left elbow joint with rotation of the forearm. Disinhibited, euphoric, decreased sense of distance. Speech is phrasal.

An examination was carried out: biochemical blood test, ECG, ultrasound of internal organs without pathology. According to MRI of the brain: local atrophic, multifocal small-focal cystic-gliotic changes in the right frontoparietal region. Psychologist: intellectual development does not correspond to age level. Oculist: no pathology detected. EEG: moderate functional-organic changes. Regional epileptiform activity in the right central region, similar in morphology to the rolandic one. Video-EEG sleep monitoring: pronounced changes in BEA, expressed in a delay in the formation of basic rhythms, persistent epileptiform activity in the frontal regions of the right hemisphere of the brain, intensifying during sleep. Ictal EEG is characteristic of paroxysms of an epileptic nature; probable localization of the focus of epiactivity in the supplementary motor zone of the frontal lobe of the right hemisphere. The presence of nocturnal paroxysmal dystonia cannot be completely excluded.

Receives therapy: depakine chrono - 500 mg/day, finlepsin retard - 200 mg/day, mydocalm 0.05 - 1 tablet 3 times a day, phenibut 0.25 - 1/2 tablet at night, nacom - 1/4 tablet in the morning . During treatment, no epileptic seizures were observed; rare dystonic attacks during sleep persisted.

The genetics of paroxysmal dyskinesias are presented in Table 2. It should be noted that in our country genetic diagnosis of paroxysmal dyskinesias is not yet carried out. The true incidence of paroxysmal dyskinesias in the general population is unknown because these conditions are commonly misdiagnosed as other diseases. The patients mentioned above were observed for a long time with a diagnosis of epilepsy (one form or another) and received antiepileptic therapy for a long time, which had a different effect on hyperkinetic attacks. The etiology of secondary paroxysmal dyskinesias includes multiple sclerosis, perinatal brain lesions and cerebral palsy, psychogenia, traumatic brain injury, encephalitis, tumors, pathology of the thyroid gland and Fahr's disease, cerebral dysgenesis, strokes, diabetes mellitus, etc. Case histories are presented in this case. two children with cerebral palsy (paroxysmal dyskinesia is symptomatic) [6].

Researchers recognize dysfunction of the basal ganglia as the leading link in pathogenesis. In some patients, positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) revealed changes in catecholamine metabolism. In addition, levodopa (a precursor of dopamine neurotransmitters) or antipsychotics (dopamine antagonists) were effective in a number of patients. In animal studies of PGD, increasing the activity of the main inhibitory neurotransmitter, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), reduces the severity and frequency of attacks. It is known that anticonvulsants—phenobarbital, valproate, and benzodiazepines—have a GABAergic effect. In clinical observations in patients with PGD, the effectiveness of anticonvulsants was noted, and in cases of PNCD, the course of the disease was mitigated with the use of only valproate and phenobarbital. This proves that the forms of paroxysmal dyskinesia are based on different mechanisms. However, more detailed studies of their pathogenesis have not been carried out to date.

The morphological substrate of paroxysmal dyskinesias is unknown. Since region 2 of chromosome (2q33–q35), damaged during paroxysmal dyskinesias, contains genes for membrane channels, there is a point of view that they are “channelopathies,” i.e., they arise as a result of abnormal operation of electrical channels of the cytoplasmic membrane [2]. Disruption of the channels leads to changes in ion concentrations in the cell and extracellular space. Mutations of the same genes have been found in some other channelopathies, for example familial hyper- or hypokalemic paralysis, paroxysmal ataxia.

Diagnosis of paroxysmal dyskinesia is based on clinical symptoms (duration and frequency of attacks, “provoking” factors; the presence of similar manifestations in relatives). Laboratory tests, EEG (preferably monitoring during an attack of hyperkinesis), MRI should be carried out - all this will exclude diseases with a similar clinical picture, as well as identify current diseases in which paroxysmal dyskinesia is secondary. Idiopathic paroxysmal dyskinesias are not characterized by changes on MRI or computed tomography. The question remains whether paroxysmal dyskinesias are epilepsies. A number of researchers classify paroxysmal dyskinesias as epilepsies, based on clinical manifestations (paroxysmality, precursors, effect of antiepileptic drugs). Other authors indicate that during the attack there are no changes in the EEG, and there are no changes in consciousness and behavior after the attack. Cases of registration of nonspecific pathological patterns on the EEG in patients with paroxysmal dyskinesia and the “coexistence” of paroxysmal dyskinesia and epilepsy in one patient have been described [2, 4]. It is especially difficult to distinguish nocturnal attacks of PCH from nocturnal frontal seizures in epilepsy, especially since antiepileptic drugs are effective in both cases. The only method that allows a correct diagnosis is nighttime video-EEG monitoring, which does not reveal epileptiform activity during night attacks of hypnogenic paroxysmal dystonia [1]. The differential diagnostic algorithm is presented in the figure. From our point of view, paroxysmal dyskinesias are not epilepsies for several reasons:

- they generally have a benign course and are not complicated by an increase in behavioral changes in the personality;

- hyperkinesis attacks are not accompanied by epileptiform activity on the EEG;

- even in the case of a status course (second example), attacks of hyperkinesis do not cause disturbances of consciousness.

Treating PD is very difficult. Unified recommendations for therapy have not been developed. In our opinion, the difficulty of selecting therapy is associated with pronounced fluctuations in endogenous catecholamines in the attack and inter-attack periods. Perhaps that is why, to stop attacks of hyperkinesis (in an acute state), it is better to prescribe antipsychotics (the drug of choice is tiapridal), and to prevent attacks, it is better to prescribe a combination of Nakoma and an antiepileptic drug (Depakine/Frisium).

At the same time, this regimen cannot be considered as a “hard” recommendation for each patient, since in some cases other drugs are also effective (finlepsin, propranolol, high doses of piracetam, etc.). Of course, the likelihood of side effects as a result of treatment should also be taken into account, since attacks regress with age.

Literature

- Mukhin K. Yu., Maksimova E. V., Glukhova L. Yu., Petrukhin A. S., Mironov M. B., Gaman O. V. A family case of paroxysmal kinesogenic choreoathetosis // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. 2000. No. 8. P. 40–43.

- Berkovic SF Paroxysmal movement disorders and epilepsy. Links across the channel//Neurology. 2000; 55(2): 169–170.

- Fahn S. The paroxysmal dyskinesias//Movement Disorders. Oxford, England: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994; 3: 310–345.

- Hirata K., Katayama S., Saito T. et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis with abnormal electroencephalogram during attacks//Epilepsia. 1991; 32(4): 492–494.

- Sadamatsu M., Masui A., Sakai T., Kunugi H., Nanko S., Kato N. Familial paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis: an electrophysiologic and genotypic analysis//Epilepsia. 1999; 40(7):942–949.

- Swoboda KJ, Soong BW, McKenna C. et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia and infantile convulsions. Clinical and linkage studies//Neurology. 2000; 55:224–230.

M. Yu. Bobylova E. S. Ilyina , Candidate of Medical Sciences S. V. Pilia M. B. Mironov , Candidate of Medical Sciences I. A. Vasilyeva A. A. Kholin , Candidate of Medical Sciences S. V. Mikhailova , Candidate of Medical Sciences Sciences A. S. Petrukhin , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the Russian State Medical University, Russian Children's Clinical Hospital of the Russian Federation, Moscow