Epilepsy is a process associated with metabolic disorders in the brain, which causes seizures. They are divided into convulsive and focal or generalized and partial, which involve both hemispheres or one, respectively. During a seizure, pathological excitations occur in the tissues, which provoke a change in impulses emanating from neurons. Focality is expressed in the localization of the lesion, based on which the treatment is based. To most accurately determine the focus, special techniques and trained specialists with extensive experience are required. The Yusupov Hospital has a specialized neurological clinic that provides high-quality diagnostics and effective treatment for patients with this disease.

What is partial epilepsy

A change in the structure of the cerebral cortex in a specific area is called partial epilepsy. This phenomenon is accompanied by chaotic nerve impulses emitted by neurons. Signals are sent to all cells associated with the affected area. The clinical picture reflects a seizure.

The main parameter adopted for classification is the localization of the functional disorder, which determines the observed picture during a seizure. The following types of localization are distinguished: temporal, frontal, occipital, parietal.

Expert opinion

Author: Daria Olegovna Gromova

Neurologist

Epilepsy has been considered one of the most dangerous and common neurological pathologies for many years. According to WHO statistics, in Russia, patients suffering from seizures account for about 2.5% of cases. The variety of forms of epileptic seizures can make diagnosis difficult. Partial epilepsy most often occurs in childhood. Until now, doctors have not been able to establish the exact causes of the disease. Great importance is attached to intrauterine development disorders and complicated childbirth.

At the Yusupov Hospital, experienced neurologists and epileptologists diagnose partial epilepsy using modern medical equipment: CT, MRI, EEG. Thanks to this, it is possible to quickly determine the location of the pathological focus. Therapy is selected individually for each patient. The drugs used meet European quality and safety standards. Patients at the Yusupov Hospital are provided with recommendations to reduce the risk of developing recurrent attacks. It has been proven that if medical prescriptions and preventive measures are followed, 60-70% of patients enter a state of long-term remission.

Types of partial seizures

As described earlier, several options for the development of this type of disease are possible. Let's take a closer look at each of them:

- The temporal one occupies the position of the most common type, accounting for 50-60% of all cases associated with distortion of neural connections.

- Frontal is the second most common manifestation; in approximately 25% of cases the disease is associated with this pathology.

- Occipital appears quite rarely, in no more than 10% of patients.

- Parietal almost never occurs and has a probability of occurrence of less than 1%.

The localization of the lesion is determined using an EEG (electroencephalogram). Most often, diagnosis is carried out while the patient is at rest, but the most accurate results can be obtained only during an attack. To create such a situation, with the consent of the patient, special means are used.

In addition to classification according to local criteria, there is also a system of differences based on severity. The following forms are distinguished:

- Simple - not accompanied by a distortion of consciousness, manifestations are variable and determined by the region.

- Complex - simple seizures with simultaneous impairment of consciousness.

- Secondary generalized (convulsive) - develops from simple and complex seizures, accompanied by convulsions.

Seizures

2. Seizures

Epileptic seizures are characterized by: a) sudden onset; b) short duration (from fractions of a second to 5–10 minutes); c) spontaneous termination; d) stereotypy at this stage of the disease.

2.1. Classification. According to the modern classification, the following types of epileptic seizures are distinguished.

1. Partial (focal, local) seizures:

1.1. Simple partial seizures:

1.1.1. motor seizures:

- focal motor without march;

- focal motor with march (Jacksonian seizures);

- adversive;

- postural;

- phonatory;

1.1.2. sensory seizures:

- somatosensory;

- visual;

- olfactory;

- taste;

- with dizziness;

1.1.3. vegetative-visceral seizures;

1.1.4. seizures with mental dysfunction:

- aphasic;

- dysmnestic;

- with impaired thinking;

- emotional-affective;

- illusory;

- hallucinatory;

1.1.5. complex partial seizures:

a) beginning with simple partial seizures followed by disturbance of consciousness:

- beginning with a simple partial seizure followed by loss of consciousness;

- beginning with a simple partial seizure with subsequent disturbance of consciousness and motor automatisms;

b) beginning with a disturbance of consciousness:

- only with impaired consciousness;

- with motor automatisms;

1.1.6. partial seizures with secondary generalization:

- simple partial seizures leading to generalized convulsions;

- complex partial seizures leading to generalized seizures;

- simple partial seizures, developing into complex partial seizures with the subsequent occurrence of generalized convulsive seizures;

1.1.7. generalized seizures;

1.1.8. absence seizures:

1. typical absence seizures:

- only with impaired consciousness;

- with a slight clonic component;

- with an atonic component;

- with a tonic component;

- with automatisms;

- with a vegetative component;

2. atypical absence seizures:

- the changes are more pronounced than with typical absence seizures;

- the onset and/or cessation of seizures does not occur suddenly, but gradually;

1.1.9. myoclonic seizures;

1.1.10. clonic seizures;

1.1.11. tonic seizures;

1.1.12. tonic-clonic seizures;

1.1.13. atonic (astatic) seizures;

1.1.14 unclassifiable seizures.

2.2. Partial seizures. They arise as a result of focal neuronal discharges from a localized area of one hemisphere. Simple partial seizures occur without impairment of consciousness, complex partial seizures occur with impairment of consciousness. As the discharge spreads, simple partial seizures can develop into complex seizures, and simple and complex seizures can transform into secondary generalized seizures. Partial seizures predominate in 60% of patients.

1) Simple partial seizures. Previously, they were designated by the terms “aura” or “signal-symptom” if they began a secondarily generalized seizure. The nature of the aura indicates the localization of the epileptic focus.

When the latter is localized in the anterior central gyrus, seizures are observed in the form of running (for example, running in a circle - “manege running”) or rotation around the axis of the body (rotatory aura), violent screaming, forced singing, psychomotor agitation, sometimes with an act of aggression, episodes of exhibitionism , kleptomania, pyromania.

With a visual aura, photopsia (phosphrenes) occur - elementary visual hallucinations (“sparks”, “stars”, “flashes”, etc.). Vision may deteriorate sharply, even to the point of complete loss. The epileptic focus is localized in the primary cortical vision center in the occipital lobe of the brain.

With an auditory aura, acoasmas are observed - elementary auditory hallucinations (“noise”, “crackling”, “squeaking”, etc.). The epileptic focus is localized in the primary hearing center - Heschl's gyrus, located in the posterior parts of the superior temporal lobe of the brain. The temporal aura can also manifest itself as senestopathic sensations, olfactory or verbal hallucinations, a feeling of the unreality of what is happening, its alienness, danger, comedy, etc.

With an olfactory aura, olfactory hallucinations occur - an imaginary sensation of a pleasant or unpleasant odor, often completely unfamiliar. An olfactory aura can be difficult to distinguish from a gustatory aura, as olfactory and gustatory hallucinations may occur simultaneously. The focus of epileptic activity is usually found in the anterosuperior part of the hippocampus. The aura can be viscerosensory (in the form of an unpleasant sensation in the epigastrium, rising upward), visceromotor (for example, in the form of constriction and dilation of the pupil, redness or pallor of the skin, pain in the stomach, increased intestinal motility, raising hair on the skin, rapid blinking). There is an aura in the form of dizziness, reminiscent of Meniere's syndrome, in the form of mentism (violent flow of thoughts), sperrung (forced suspension of thinking) and many others. etc.

The aura is a simple partial seizure without subsequent generalization (isolated aura) or developing into a convulsive seizure. Its duration is several seconds (sometimes fractions of a second), so patients most often do not have time to take precautions against injury when falling at the beginning of a convulsive attack. There is no amnesia for aura.

Simple partial motor or Jacksonian seizures usually begin with twitching of the corners of the mouth, then other facial muscles, tongue, after which the “march” moves to the arms, torso and legs of the same side.

2) Simple partial vegetative-visceral seizures. They appear as isolated paroxysms, but can transform into complex partial seizures or serve as the aura of a secondarily generalized seizure. Often the first paroxysmal manifestations of epilepsy are vegetative-visceral seizures.

Many researchers considered vegetative-visceral seizures as a result of damage to the interstitial brain (diencephalic region of the brain) and called them diencephalic. Within the framework of diencephalic epilepsy, we distinguished Meniere's syndrome (ear epilepsy), bronchial asthma (pulmonary epilepsy, epileptic asthma), various vasomotor attacks, attacks of sudden sweating, attacks of hyperthermia, attacks of acute abdomen (abdominal epilepsy), attacks of heat, cold, chills, bulimia, anorexia, tachypnea, tachycardia, increased blood pressure, thirst, polyuria, various pains (cardialgia, epigastric and abdominal algia).

Currently, the following variants of simple partial vegetative-visceral seizures are distinguished.

2.1. Respiratory or hyperventilation seizures. They manifest themselves as multisystem mental, vegetative, algic, muscular-tonic disorders caused by primary dysfunction of the nervous system of an organic nature and leading to the formation of pathological breathing. The core of respiratory seizures is considered to be a triad of signs: a) increased breathing; b) paresthesia and c) tetany. The main disorder is shortness of breath (dyspnea), which is felt as insufficiency of breathing, difficulty in performing respiratory movements, and painful breathing.

Patients with “lack of full inhalation” (“lack of saturation with inhalation”) feel that the air does not penetrate deep into the lungs, but is retained somewhere at the level of the middle or lower third of the sternum. One also feels a “lump in the throat”, some kind of obstacle, a “damper”, a “valve” in the path of air movement, “squeezing” of the breath inside or “squeezing” it from the outside. At the same time, patients tend to take deeper breaths and resort to additional movements of the arms, torso, and neck in order to “expand the chest” as much as possible for air access. If you manage to take a deep breath, the painful feeling of lack of air immediately disappears, but after a few breathing movements it may return. Then the patients begin to breathe frequently and deeply, open windows and doors wide, run out into the street, and become, in their words, “air maniacs.”

Breathing eventually becomes frequent, arrhythmic, accompanied by deep breaths (“sad sighs”) followed by long pauses. Focusing on breathing leads to the development of “respiratory bulimia”: “I breathe, I breathe, and I can’t get enough.” The attention of other patients may be focused not on hyperventilation, but on cardiovascular manifestations (cardialgia, cardiac arrhythmias, vascular dystonia); painful breathing sensations are attributed to heart pathology. Respiratory sensations (shortness of breath, lack of air) are a subtle indicator of anxiety disorders, which patients themselves usually do not realize and do not report to the doctor. Cardiophobia, in turn, further intensifies anxiety and thereby maintains a high level of psycho-vegetative tension.

2.2. Cardiac seizures. Characterized by the following manifestations:

- attacks of cardialgia are pain in the heart area that do not have clear signs of classic angina. The pain is very diverse: aching, aching, pressing, gnawing, raw, squeezing, etc., reminiscent of senestopathy in its diversity. Patients' complaints often sound quite pretentious. For example, “the heart is like in a vice,” “the heart is tearing apart like claws,” “like a hot nail in the left half of the chest,” “the top of the heart hurts.” Sometimes complaints acquire a distinct objective character and come close to reports of visceral hallucinations. The pain may also be of muscular origin. Sometimes they radiate to the left hypochondrium, left axillary region, left shoulder, under the shoulder blade, in the leg, accompanied by hyperesthesia and a feeling of numbness. Often, especially at the height of fear of death, pain in the heart area is accompanied by a feeling of lack of air, incomplete inhalation.

2.3. Heart rhythm disorder syndrome. This is a subjective feeling of a rapid heartbeat, a slowdown in the heart rate, a temporary stoppage of the heartbeat, an interruption in the heartbeat: “the heart beats anxiously in the chest”, “the heart hits the chest hard”, etc., objectively the heart rhythm is not disturbed or tachycardia ( up to 120 beats per minute) is caused by emotional stress. Often there are unpleasant sensations in the heart area, increased blood pressure, sensations of numbness and coldness in the extremities, lack of air, anxiety and fear of death.

2.4. Syndrome of impaired autonomic regulation of blood pressure. Available in three variants:

- arterial hypertension syndrome. Pressing, squeezing, pulsating, burning, bursting headaches are typical; blood pressure rises moderately - up to 160/95 mm Hg. Art.;

- arterial hypotension syndrome. Characterized by headaches in the temporal and frontoparietal regions, accompanied by dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Blood pressure decreases to 90/50 mm Hg. Art.;

- blood pressure lability syndrome. Manifested by episodes of increased or decreased blood pressure.

2.5. Visceral (epigastric, abdominal) seizures. They are characterized by a feeling of heaviness and fullness in the epigastric region, a feeling of fullness in the stomach, burning, and pain. Usually accompanied by aerophagia followed by noisy belching, vomiting, pallor of the skin, tachy- or bradycardia, decreased blood pressure, “vomiting cramps,” a feeling of abdominal discomfort, an imperative false urge to defecate, heaviness, rumbling, distension, cramping pain in the abdomen, a feeling of bloating , flatulence. Characterized by the appearance of a specific “ascending epileptic sensation”, described by patients as pain, heartburn and nausea emanating from the abdomen and rising to the throat with a feeling of compression, compression of the neck, a lump in the throat, often followed by blackout and convulsions.

Patients often use the term “pain” to refer to various senestopathies; in this case, they mean abdominal psychalgia, from which they suffer no less than from the pain itself. Senestopathic sensations are characterized by:

- variability in the location, intensity and nature of pain;

- unusual descriptions of such pain in terms of their nature and localization (“burning”, “twisting”, “biting”, “burning the apex of the left lung”, “pain in the form of longitudinal parallel lines”, etc.);

- often the objective nature of senestopathy, which is why their manifestations are close to visceral hallucinations and hallucinations of transformation (“a hot and pulsating ball is felt inside,” “the walls of the stomach are dissecting,” etc.);

- dissociation between the description of pain as “excessive”, “unbearable”, on the one hand, and the satisfactory objective condition of patients, on the other.

Often patients, especially children, have difficulty describing their sensations or resort to metaphors such as “fear in the stomach” (unusual localization of emotions in adults is known as Minor’s symptom, one of the manifestations of allesthesia). After the completion of abdominal seizures, post-ictal disorders are observed, such as severe asthenia, drowsiness, lethargy, and stupor.

2.6. Orgiastic attacks. Paroxysmal sexual sensations are more common in women and are characterized by pleasant sensations of warmth in the lower abdomen, irresistible sexual desire, increasing sexual arousal, which often ends in orgasm. In this case, vaginal hypersecretion and contraction of the muscles of the vagina, perineum, and thighs may appear. Some patients express their emotional state with the words “happiness”, “delight”, “bliss”.

2.7. Vasomotor (vegetative) seizures. They are characterized by pronounced vasomotor phenomena: facial hyperemia, thirst, polyuria, tachycardia, sweating, bulimia or anorexia, increased blood pressure, algic symptoms, body hyperthermia. Among the seizures with impaired thermoregulation there are:

- paroxysmal hyperthermia (temperature crises). It manifests itself as a sudden increase in body temperature to 39–41°C, accompanied by chills-like hyperkinesis, a feeling of internal tension, headache, and facial flushing. After a lytic decrease in temperature, weakness and weakness persist for some time;

- paroxysmal hypothermia. Manifested by a decrease in body temperature to 35°C and below, weakness, decreased blood pressure, sweating, decreased performance;

- chill-like hyperkinesis. It is characterized by the sudden appearance of a feeling of chills, accompanied by piloerection (goose bumps), increased blood pressure, tachycardia, pallor of the skin, and occasionally a rise in body temperature;

- chill syndrome. It is characterized by thermal hallucinations in the form of a feeling of “coldness in the body” or different parts of the body. Body temperature remains normal, sometimes low-grade. In addition, lability of blood pressure and pulse, hyperhidrosis, and hyperventilation disorders are noted.

Often, these viscerovegetative paroxysms are mistakenly regarded as manifestations of vegetative-vascular dystonia, neurocirculatory dystonia, or autonomic neurosis, which leads to inadequate therapy.

For vegetative epileptic seizures the following are considered characteristic:

- weak expression or absence of provoking factors for their occurrence, including psychogenic ones;

- short duration (duration does not exceed 10 minutes);

- convulsive twitching during an attack;

- tendency to have serial attacks;

- post-paroxysmal stunned consciousness and disorientation in the environment;

- combination with other seizures;

- “photographic” identity of vegetative-visceral paroxysms at a given segment of the course of the disease;

- EEG changes characteristic of epilepsy in the interictal period: 1) hypersynchronous discharges; 2) bilateral bursts of high-amplitude activity; 3) peak-wave complexes - slow wave; 4) other specific epileptic changes in brain biopotentials.

It has now been established that the epileptic focus during vegetative-visceral seizures can be localized not only in the diencephalic region, but also in other brain structures, such as the amygdala-hippocampal region, hypothalamus, opercular region, orbitofrontal region, parietal region, temporal lobes of the brain.

3) Simple partial seizures with mental dysfunction. The most common seizures occur with sensations of “already seen”, “already heard”, “already experienced” - in 26.4%. Seizures with derealization phenomena occur less frequently - in 12.8%. Seizures with symptoms of allometamorphopsia are observed in 13.7%, autometamorphopsia - in 12.3%, depersonalization - in 11.1%, hallucinatory seizures - in 7.4%, emotional-affective seizures - in 5.3%, ideational seizures - in in 6.4%, seizures of hyperrealization – in 4.6%.

3.1. Dysmnestic seizures - with the phenomena of “already seen” (deja vu), “already heard” (deja entendu), “already experienced” (deja eprouve). They are characterized by a feeling of “remembering the present,” in which current impressions and experiences at the moment are perceived with the nature of their memories. It seems that what is happening or being experienced has already happened, and now it is only being repeated in the form of its memory. The disorder occurs in many variants (Sumbaev I.S., 1945). For example, a “present memory” may be repeated, thereby resembling the phenomenon of echonesia, perceived as happening to someone else, it may contain banknotes, etc.

In contrast to 50–60% of adequate individuals who at least occasionally have a fleeting feeling of “already seen,” in patients with seizures this phenomenon lasts up to 5 minutes or more and is accompanied by a feeling of confidence that it is a repetition of what is taking place. happened sometime before. The epileptic focus is localized in the amygdala-hippocampal region; with a focus in the subdominant hemisphere, seizures occur 3–9 times more often than with a focus in the dominant hemisphere.

3.2. Ideation seizures. They include various ideation and speech disorders: alien, forcibly intruding thoughts of absurd content, usually not stored in memory; sudden onset of unexpected thoughts, episodes of broken or incoherent thinking, stopping thinking with a feeling of emptiness in the head, "spinning" the same thought, experiencing splitting of thinking and speech, paralysis of speech, forced speech, difficulty constructing phrases, understanding someone's speech another, memory lapses when you cannot remember something known. Ideation seizures are considered characteristic of frontal and temporal lobe epilepsy. It is believed that such seizures in children may cause learning difficulties. According to modern concepts, transient cognitive impairment is caused by a generalized epileptic discharge of slow waves with a frequency of 3 Hz and a duration of more than 3 seconds.

3.3. Emotional-affective attacks. Includes a range of clinical options:

- seizures in the form of depressive disorder. Paroxysmal depression of mood with melancholy and guilt is typical, while what is happening around is experienced as something unnatural, lifeless, and meaningless;

- maniform seizures. Characterized by manic paroxysms with experiences of happiness, delight, jubilation, ecstasy, while patients usually remain passive, lethargic, as if peaceful, completely captured by their mood, focused exclusively on it, losing the ability to perceive what is happening around them;

- dysphoric seizures. These are paroxysms of a melancholy-angry mood with fear and extreme irritation, verbal and/or physical aggressiveness, lasting no more than 5 minutes. The epileptic focus is often found in the structures of the limbic system;

- illusory seizures. They are characterized by an influx of illusions of different sensory modalities and different contents, including fantastic ones (pareidolic illusions). Some researchers believe that illusory seizures are a type of psychosensory seizure;

- seizures with symptoms of allometamorphopsia. In this case, surrounding objects are perceived as deformed, increased or decreased in size, distant, elongated, twisted, moving, falling, etc. Sometimes a state of optical storm occurs with the experience of rapid and chaotic movement of perceived objects. The epileptic focus is often found at the junction of the temporal, parietal and occipital lobes of the brain;

- seizures with symptoms of autometamorphopsia. Various disturbances of the “body scheme” are noted: macrosomia, microsomia, changes in the shape of the body or its parts, schizosomy, etc.;

- attacks of autopsychic depersonalization. They are experienced with a feeling of alteration of the mental and physical “I”. For example, the consciousness of one’s “I” may be lost (“my “I” disappears”), the “I” is perceived as belonging to someone else, there is a feeling of fragmentation of the “I” into separate subpersonalities, a feeling of devitalization appears (“I am dying”, “I’m dead”), desomatization (“I don’t feel my body,” “my hands have disappeared”), there is a feeling of alienation of one’s own mental acts (“thoughts are not mine,” “emotions come to me from the outside”) and many others. etc. Paroxysms last from a few seconds to 5–10 minutes. The epileptic focus is often detected in the right parietotemporal region of the brain;

- attacks of derealization. They proceed with a feeling of unreality of what is perceived, as if the surroundings are dreams, exist in dreams, in the imagination, and do not exist in reality;

- attacks of hyperrealization. They are characterized by a feeling of extraordinary sensory brightness of what is perceived, a feeling of its closeness to the patient’s personality, and being captured by the special meaning of what is happening. This state is also known as the state of super-awakeness, super-consciousness. The epileptic focus in the last two cases is more often found in the posterior parts of the superior temporal gyrus;

- attacks of olfactory hallucinations. Repulsive deceptions of taste occur more often than pleasant ones; imaginary smells may be completely unfamiliar (it is possible that in the latter case a state of “never perceived before” - jamais vu) also arises. Along with olfactory hallucinations, taste hallucinations often occur;

- attacks of visual hallucinations. They are more common than other types of hallucinatory seizures. These can be either elementary optical illusions or complex ones with a wide variety of content;

- attacks of auditory hallucinations. Both elementary auditory deceptions and very complex ones arise, including verbal and musical ones (when, for example, sacred music is played).

4) Complex (complex) partial seizures. Complex partial seizures with automatisms (so-called psychomotor seizures) are more common. At the same time, against the background of a twilight state of consciousness, actions of varying degrees of complexity are performed. The duration of the seizures reaches 5 minutes, and congrade amnesia usually occurs (during the period of impaired consciousness). The following types of psychomotor seizures are distinguished:

- attacks of oral automatism or oral attacks. Manifested by opercular actions such as chewing, swallowing, licking, slurping, sucking, etc.;

- automatism of gestures. Actions such as rubbing hands, acts of expression, manipulation of clothing, objects, furniture are performed;

- speech automatisms. Words and phrases that are not addressed to anyone are automatically pronounced, sometimes seemingly meaningful, but more often devoid of any specific meaning;

- sexual automatisms. Manifested by acts of masturbation, depraved acts, exhibitionism, etc.;

- ambulatory automatisms. Patients move around: walk, run;

- somnambulism. These are ambulatory automatisms that occur during slow-wave sleep.

5) Generalized seizures. There are absence seizures and tonic-clonic seizures.

5.1. Absence (French absens - absence). The former name was petit mal, small seizure (Esquirol, 1815). In typical absence seizures, the EEG records specific bilateral synchronous activity in the form of peak-wave complexes with a frequency of 3 Hz in the brain stem structures. The following types of absence seizures are distinguished:

- typical or simple absence seizures. They manifest themselves as a sudden short-term loss of consciousness for up to 20 seconds. During a seizure, the patient freezes, interrupting previous actions, his eyes focus on one point, his gaze becomes absent, his face turns pale. The attack ends just as quickly. Some patients call seizures “thoughts,” but this name is inaccurate (actually, “thoughts” were first described by F.M. Dostoevsky; they represent periods of cessation of mental activity and motor numbness without turning off consciousness). Typically, patients remember the moments of turning off and turning on consciousness, the interval between which is amnesic;

- absences are called complex, during which there is a slight clonic component: twitching of the eyelids, eyeballs, facial muscles - myoclonic absence, as well as absences with a tonic component - tonic absence. In young children, myoclonic absence is manifested by lightning-fast shaking of the whole body. In turn, absence seizures with a tonic component occur in children in the form of: a) propulsive seizures - with flexion movements (nodding, pecking, convulsions of the eastern greeting, occurring serially); b) in older children, retropulsive seizures are observed - with extension movements of the head and torso. In addition, absence seizures with automatisms are observed - opercular and other automatisms occur during a seizure. Their duration is up to 15 seconds.

5.2. Tonic-clonic seizure (grand mal, big seizure). It is considered as a nonspecific reaction of the brain to the action of various pathogenic factors. This reaction is especially typical for children. A tonic-clonic seizure occurs in several stages:

- precursors of a seizure, or epileptic prodromes. They occur several hours, less often days, before the onset of a seizure. They manifest themselves as nonspecific disorders, such as malaise, headache, depressed mood, dysphoria, euphoria, anxiety, fear, irritability, etc. Some patients learn from these signs that a seizure is approaching and can take certain precautions;

- aura of a seizure. Tonic-clonic seizures that continue after the aura are called complex partial seizures (the old name is secondary generalized seizures). Primary generalized seizures do not have an aura; they begin with an instant loss of consciousness (the patient falls into a state of epileptic coma in a split second), an instant loss of muscle tone and a fall (the patient falls as if knocked down from any position and location), followed by sometimes an inhuman scream, which indicates the development of tonic spasms of all voluntary muscles of the body, including the respiratory muscles and muscles of the larynx;

- tonic phase of the seizure. Accompanied by tongue biting, urination, sometimes defecation and ejaculation. The voluntary muscles of the body are in a state of extreme tension (bone fractures even occur), and there is no breathing. Due to the uneven distribution of muscle tone, the patient's body can take various forced postures. The skin is pale, then begins to turn blue. This phase lasts up to 30 seconds;

- clonic phase. Clonic spasms predominate in the flexor muscles. Clonus of the respiratory muscles is manifested by intermittent and noisy breathing. The skin is cyanotic, foam is released from the mouth, stained with blood when bitten. The clonic phase lasts up to 2 minutes;

- the sleep phase, more precisely, the recovery from the state of epileptic coma through stupor and stunned consciousness (doubtfulness, obscurity). Some patients quickly regain consciousness, others linger in this phase for up to several hours. Upon exiting a coma, post-ictal twilight states of consciousness with psychomotor agitation and aggression may develop. The entire period of time, from the end of the aura to the restoration of clear consciousness, is amnesic. Patients guess about the fact of a seizure based on the circumstances accompanying it, memory loss. They sometimes find out about seizures during sleep themselves, if they dream about one thing every time, by bites, post-seizure disorders, but more often - by reports from someone close to them;

- post-ictal disorders. They occur in some patients and can last up to 2–3 days. At this time, a variety of mental and neurological disorders may occur: headaches, fatigue, mood disorders, memory, speech, bradyphrenia, sleep disturbances, changes in skin and tendon reflexes, myoclonic twitching, etc., in some patients this Small seizures occur or become more frequent over time.

Major seizures, if they lack one phase or several phases at the same time, are traditionally called abortive. These are, for example, myoclonic seizures, tonic seizures, seizures of epileptic coma with loss of the convulsive component. The latter, if they occur for a short time, can resemble fainting states - syncope.

Minor and major seizures can be single, occurring with different frequencies, grouped in a series of seizures with short intervals between them, however, sufficient for the patient to recover from the next attack, or occur in the form of status epilepticus, when the next seizure is layered on the consequences of the previous one and There are up to a hundred or more seizures within 1–2 days. Seizures with mental disorders (simple partial mental and complex partial seizures with mental disorders) can also occur according to the type of status epilepticus, and sometimes there is a similarity with schizophrenic psychosis.

Status epilepticus of tonic-clonic seizures is usually accompanied by vital disorders (hyperthermia, cerebral edema with possible wedging of its structures between the layers of the dura mater, respiratory and cardiovascular disorders, metabolic disorders, disturbances of the ion and water-salt balance, aspiration of vomit, etc. .). It stops on its own in no more than half of the cases, and this happens only at the beginning of the status. As it drags on, the likelihood of spontaneous termination of the status becomes less and less likely.

Status epilepticus requires, if possible, early and emergency intervention, the use of anticonvulsants (the most indicated is a single or, if ineffective, repeated intravenous administration of 2–4 ml of 0.5% seduxen solution), resuscitation measures.

Status epilepticus most often occurs when the therapeutic regimen is violated, in particular due to the lack of the required anticonvulsant, replacement with another drug, early cessation of treatment, patient refusal of treatment, untimely change in the dosage of the drug when the body temperature rises, the development of intercurrent diseases, especially accompanied by an increase in body temperature, since convulsive readiness increases by 30% or more.

6) Situationally determined seizures. Typically these are tonic-clonic seizures that occur as a reaction to various harmful conditions. In accordance with the latter, seizures caused by:

- alcohol and drug intoxication;

- poisoning with barbiturates, psychotropic drugs;

- traumatic brain injury in the acute period of its course;

- acute toxic encephalopathy, especially caused by the action of the so-called. convulsive poisons (strychnine, corazole), as well as penicillin, furosemide, causative agents of tetanus, rabies, etc.;

- renal and liver failure;

- hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, hypo- and hypercalcemia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia of various origins;

- severe brain damage against the background of a precomatous or comatose state;

- severe overheating and hypothermia;

- exposure to ionizing radiation, electrical trauma of varying severity.

In addition, the development of seizures can be provoked by reflex factors - reflex epilepsy. Such factors may be:

- intermittent action of photostimuli on the visual analyzer (photogenic, photosensitivity, “television” seizures, “Pokemon” seizures, “computer” epilepsy, “Star Wars epilepsy”, etc.);

- audiogenic and musicogenic seizures;

- counting epilepsy - “mathematical” seizures, seizures when playing chess, cards, in a casino;

- epilepsy of food (separately described are “epilepsy of solid food”, “epilepsy of liquid food”, “epilepsy of apples”, etc.);

- reading epilepsy;

- epilepsy of orgasm;

- epileptic seizures in catastrophic situations.

For children, the so-called febrile seizures are generalized tonic-clonic or tonic paroxysms that occur in children aged from 3 months to 5-6 years (usually 2-3 years) against the background of an increase in body temperature of more than 38°C. In a third of children, when body temperature rises, they recur. Febrile seizures occur in 3–5% of children (in some regions of the world - in 8–14% of children). As a rule, convulsive attacks occur against the background of a concomitant infectious disease (usually respiratory viral) and do not have a damaging effect on the brain, but sometimes this is possible. There are simple and complex febrile seizures.

1. Simple febrile seizures account for up to 90% of all febrile seizures. They are characterized by:

- sporadic convulsive episodes;

- short duration (up to 15 minutes);

- generalized picture of a seizure (loss of consciousness, symmetrical tonic-clonic convulsions).

2. Complex febrile seizures are characterized by:

- repeatability throughout the day;

- duration more than 15 minutes;

- focal (focal) character - looking away upward or to the side, twitching of one limb or part of it, stopping gaze.

In most cases, febrile seizures disappear by the age of 5–6 years and do not recur subsequently. 4–5% of patients subsequently develop epilepsy. This most often occurs in cases of complex febrile seizures. Even a single episode of complex febrile seizures indicates a significant risk of developing epilepsy; patients require long-term observation by a neurologist and pediatrician; if the seizure recurs, anticonvulsant therapy is required.

Risk factors for the development of epilepsy are considered to be early onset of febrile seizures (before 1 year), focal nature of seizures, neurological symptoms after the end of the seizure, familial nature of febrile seizures, long-term changes in the EEG, recurrence of seizures with somatic diseases, recurrence of seizures at body temperature less than 38°C , serial and status nature of convulsive seizures, their recurrence after 3 years.

If febrile seizures are of a protracted, serial or status nature, treatment is necessary, which is carried out according to the rules for the treatment of status epilepticus. Antipyretics are recommended as preventive measures (avoid prescribing pyrazolone derivatives!).

Return to Contents

Causes of partial epilepsy

This disease is most common in children and develops due to problems during pregnancy or childbirth. For example, from undermining the development of the fetus inside the womb or from a prolonged lack of oxygen during the birth of a child.

It is possible that the disease may develop in an adult. The disease may occur as a result of injury or other brain disease and will be symptomatic. The following factors may influence its development:

- malignant and benign growths;

- circulatory dysfunction;

- hematomas;

- cyst;

- aneurysms;

- malformations;

- infectious diseases;

- stroke attacks;

- abscess;

- weak intercellular metabolism;

- congenital pathologies;

- traumatic brain injuries.

The above disorders sharply increase the risk of developing a defect due to the formation of pathological signals of altered intensity from neurons, so it is necessary to seek treatment in a timely manner.

Epilepsy and other seizure conditions

The onset of a single attack characteristic of epilepsy is possible due to the specific reaction of a living organism to the processes that have occurred in it. According to modern concepts, epilepsy is a heterogeneous group of diseases, the clinical picture of chronic cases of which is characterized by convulsive repeated attacks. The pathogenesis of this disease is based on paroxysmal discharges in the neurons of the brain. Epilepsy is characterized mainly by typical repeated seizures of various types (there are also equivalents of epileptic seizures in the form of sudden onset mood disorders (dysphoria) or characteristic disorders of consciousness (twilight stupefaction, somnambulism, trances), as well as the gradual development of personality changes characteristic of epilepsy and (or ) characteristic epileptic dementia. In some cases, epileptic psychoses are also observed, which occur acutely or chronically and are manifested by such affective disorders as fear, melancholy, aggressiveness or an increased ecstatic mood, as well as delusions, hallucinations. If the occurrence of epileptic seizures has a proven connection with somatic pathology, then we are talking about symptomatic epilepsy. In addition, within the framework of epilepsy, the so-called temporal lobe epilepsy is often distinguished, in which the convulsive focus is localized in the temporal lobe. This allocation is determined by the peculiarities of clinical manifestations characteristic of the localization of the convulsive focus in the temporal lobe of the brain. Neurologists and epileptologists are involved in the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy.

In some cases, seizures complicate the course of a neurological or somatic disease or brain injury.

Epileptic seizures can have different manifestations depending on the etiology, localization of the lesion, and EEG characteristics of the level of maturity of the nervous system at the time of the attack.

Numerous classifications are based on these and other characteristics. However, from a practical point of view, it makes sense to distinguish two categories: Primary generalized seizures

Primary generalized seizures are bilaterally symmetrical, without focal manifestations at the time of occurrence. These include two types:

- tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal)

- absence seizures (petit mal) are short periods of loss of consciousness.

Partial seizures

Partial or focal seizures are the most common manifestation of epilepsy. They arise when nerve cells are damaged in a specific area of one of the brain hemispheres and are divided into simple partial, complex partial and secondary generalized.

- simple - during such attacks there is no impairment of consciousness

- complex - attacks with a disturbance or change in consciousness, caused by areas of overexcitation of various localizations and often become generalized.

- secondary generalized seizures - typically begin in the form of a convulsive or non-convulsive partial seizure or absence seizure, followed by a bilateral spread of convulsive motor activity to all muscle groups.

Epileptic seizure

The occurrence of an epileptic attack depends on a combination of two factors in the brain itself: the activity of the seizure focus (sometimes also called epileptic) and the general convulsive readiness of the brain. Sometimes an epileptic attack is preceded by an aura (a Greek word meaning “breeze” or “breeze”). The manifestations of the aura are very diverse and depend on the location of the part of the brain whose function is impaired (that is, on the localization of the epileptic focus). Also, certain conditions of the body can be a provoking factor for an epileptic attack (epileptic attacks associated with the onset of menstruation; epileptic attacks that occur only during sleep). In addition, an epileptic seizure can be triggered by a number of environmental factors (for example, flickering light). There are a number of classifications of characteristic epileptic seizures. From a treatment point of view, the most convenient classification is based on the symptoms of attacks. It also helps to distinguish epilepsy from other paroxysmal seizure conditions.

Diagnosis of epilepsy

Electroencephalography

For the diagnosis of epilepsy and its manifestations, the method of electroencephalography (EEG), that is, the interpretation of the electroencephalogram, has become widespread. Particularly important is the presence of focal peak-wave complexes or asymmetric slow waves, indicating the presence of an epileptic focus and its localization. The presence of high convulsive readiness of the entire brain (and, accordingly, absence seizures) is indicated by generalized peak-wave complexes. However, it should always be remembered that the EEG does not reflect the presence of a diagnosis of epilepsy, but the functional state of the brain (active wakefulness, passive wakefulness, sleep and sleep phases) and can be normal even with frequent attacks. Conversely, the presence of epileptiform changes on the EEG does not always indicate epilepsy, but in some cases it is the basis for prescribing anticonvulsant therapy even without obvious seizures (epileptiform encephalopathies).

Treatment of the disease is carried out both on an outpatient basis (with a neurologist or psychiatrist) and inpatiently (in neurological hospitals and departments or in psychiatric departments - in the latter, in particular, if a patient with epilepsy has committed socially dangerous actions in a temporary mental disorder or chronic mental disorders and compulsory medical measures were applied to him). In the Russian Federation, compulsory hospitalization must be authorized by a court. In particularly difficult cases, this is possible before the judge makes a decision. Patients forcibly placed in a psychiatric hospital are recognized as incapable of work for the entire period of their stay in the hospital and have the right to receive a pension and benefits in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation on compulsory social insurance[7].

Drug treatment of epilepsy

Main article: Anticonvulsants

- Anticonvulsants, also known as anticonvulsants, reduce the frequency, duration, and in some cases completely prevent seizures.

In the treatment of epilepsy, anticonvulsants are mainly used, the use of which can continue throughout a person’s life. The choice of an anticonvulsant depends on the type of seizures, epilepsy syndromes, health status and other medications taken by the patient. In the beginning, the use of one drug is recommended. In case this does not have the desired effect, it is recommended to switch to another medicine. Two drugs are taken at the same time only if one does not work. In approximately half of the cases, the first remedy is effective, the second is effective in another 13%. The third or a combination of two can help an additional 4%. About 30% of people continue to have seizures despite treatment with anticonvulsants.

Possible drugs include phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and are approximately equally effective for both partial and generalized seizures (absence seizures, clonic seizures). In the UK, carbamazepine and lamotrigine are recommended as first-line drugs for the treatment of partial seizures, and levetiracetam and valproic acid as second-line drugs due to their cost and side effects. Valproic acid is recommended as the first-line drug for generalized seizures, and lamotrigine second. For those who do not have seizures, ethosuximide or valproic acid is recommended, which is especially effective for myoclonic and tonic or atonic seizures.

- Neurotropic drugs - can inhibit or stimulate the transmission of nervous excitation in various parts of the (central) nervous system.

- Psychoactive substances and psychotropic drugs affect the functioning of the central nervous system, leading to changes in mental state.

- Racetams are a promising subclass of psychoactive nootropic substances.

Consequences of traumatic brain injuries (concussion and its consequences, contusion of the brain, hemorrhages, hematomas), consequences of spinal trauma. ConsequencesConsequences

As already written above, medical intervention should never be neglected, even with the mildest degrees of injury. In the worst cases, this leads to undesirable consequences.

For example, in acute forms of manifestation

- depression;

- mood swings;

- partial memory impairment;

- insomnia.

Such symptoms may remain even with mild injuries, if you do not follow the clear treatment instructions of doctors.

After completion of treatment and complete recovery, to be firmly convinced that the disease has subsided, it is necessary to undergo a follow-up examination.

Concussion - as harmless as it seems Is concussion as harmless as it seems?

A concussion is considered a mild closed traumatic brain injury (CTBI), which is diagnosed more often than others. A concussion itself does not pose a threat to human life and health, provided proper treatment and adherence to the recommended regimen, but sometimes after an injury undesirable consequences develop in the form of various unpleasant symptoms.

« Back to previous page

Symptoms of partial epilepsy

When determining the area of brain damage, the first thing to pay attention to is the symptoms that the patient exhibits. They are the main signals for establishing the type of disorder and prescribing the necessary therapy.

When the temporal part is damaged, memory and sound perception are affected. The victim may think that he hears some sounds or music, although in fact there are none. He is attacked by a feeling of déjà vu, and various memories from the long past emerge. The patient is also subjected to emotional attacks, which are expressed in anxiety, anger or feelings of joy and happiness.

Manifestations of damage can be simple, complex, convulsive and combined. The most common are complex ones with automatisms and confusion. Before an attack, there is a sensation of olfactory, visual, gustatory, auditory, mental, somatosensory or vegetative-visceral aura.

The frontal lobe is responsible for motor functions, so damage in this part can be determined by chaotic uncontrolled twitching of the limbs, hands and fingers, the play of facial muscles, and eyes darting from side to side. The patient may make repeated movements of the lips and tongue, as well as stomp in one place.

Based on their form, they can distinguish simple, complex, convulsive and combined seizures. Duration is up to 1 minute, repetitions are observed. Most often occur at night. The aura is not felt.

Peculiarities:

- high duration;

- minimal impact on consciousness;

- rapid occurrence of secondary attacks;

- frequent manifestation of motor dysfunctions;

- there are automatisms before a seizure;

- the victim falls.

The occipital part of the brain is focused on the functioning of the visual organs, so damage to it will affect a person’s vision. During an attack, spots, flashing and colored lights appear in the eyes, or loss of visual fields occurs, followed by severe pain in the head, similar to a migraine.

Damage to the parietal lobe leads to sensory dysfunction. There is a localized feeling of tingling, warmth or cold at a constant ambient temperature, as well as a feeling of enlargement or shrinkage of different parts of the body.

In symptomatic partial epilepsy, there is a secondary generalization - the so-called transition from focal to generalized. In this case, the patient experiences seizures, loss of muscle tone, and paralysis.

Benign partial epilepsy of childhood

Benign partial epilepsies of childhood include:

- benign partial epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (rolandic epilepsy);

- benign partial epilepsy with occipital paroxysms;

- benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms (benign psychomotor epilepsy). The question of whether 2 more forms belong to this group is also discussed:

- atypical benign partial epilepsy:

- benign partial epilepsy with extreme somatosensory evoked potentials.

Benign partial epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. (Rolandic epilepsy)

The disease was first described by Gastaut in 1952.

Frequency. Rolandic epilepsy is relatively common and accounts for 15% of all epilepsies in children under 15 years of age. The frequency of occurrence, in comparison with absence seizures, is 4-7 times higher. Mostly males are affected.

Genetic data. Hereditary burden of epilepsy can be traced in 17-59% of cases (Blom et al, 1972; Blom, Heijbel, 1982).

Clinical characteristics. Rolandic epilepsy most often manifests at the age of 4-10 years (Blom et al, 1972). The attack usually begins with unilateral sensory sensations (numbness, tingling) in the orofaciomandibular region. In the future, tonic tension in the facial muscles may be noted; clonic or tonic-clonic twitching of the limbs is less common. When the muscles of the larynx and pharynx are involved in the process, speech disturbances are noted (inarticulate sounds, complete inability to pronounce sounds). Attacks often occur with preserved consciousness, however, with the generalization of paroxysms, loss of consciousness is possible (Nayrac, Beaussart, 1958). One of the important features of Rolandic epilepsy is the frequent occurrence of attacks at night, mainly during the phase of falling asleep, or shortly before waking up. Attacks are usually rare. They usually occur at intervals of weeks, months, and sometimes occur once. In only 20% of cases the frequency of attacks is relatively high (Lerman, 1985). Intelligence is usually normal (Lerman, 1985; Dalla Bernardina et al, 1992). A decrease in intelligence and changes in behavior are observed only in isolated cases (Beaumanoir et al, 1974; Lerman, 1985). Behavioral disorders are not caused by the disease itself, but are secondary and associated with parental “overprotection” (Lerman, 1985). The thesis about the absolute absence of pathological changes in the central nervous system in rolandic epilepsy is debatable (Morikawa et al, 1979). Lerman (1985) drew attention to the fact that in 3% of cases with Rolandic epilepsy, hemiparesis is observed. School performance in children with rolandic epilepsy is usually satisfactory, and professional skills are easy.

Data from laboratory and functional studies. EEG is a necessary method to verify the diagnosis. Rolandic epilepsy is characterized by the presence of normal basal activity and spikes of sharp waves localized in the centrotemporal areas. The frequency of spikes and sharp waves increases during sleep. During the slow-wave sleep phase, the formation of bilateral or independent foci of epileptic activity is possible (Blom et al, 1972; Dalla Bernardina et al, 1992), and in some cases, the occurrence of generalized outbreaks of “spike-wave” complexes with a frequency

3-4/sec (Lerman, 1985, 1992). It should be noted that in 30% of cases, EEG patterns typical of rolandic epilepsy are recorded only during sleep (Lerman, 1985). At the same time, the sleep profile in rolandic epilepsy is usually not changed (Nayrac, Beaussart, 1958). Noteworthy is the fact that “rolandic adhesions” are sometimes (1.2-2.4% of cases) observed in healthy people (Cavazutti et al, 1980) and in patients with certain neurological diseases (Degen et al, 1988).

The differential diagnosis should primarily be made with simple and complex focal seizures observed in symptomatic partial epilepsies. In Rolandic epilepsy, in comparison with symptomatic partial epilepsy, intelligence is usually normal, there are no pronounced behavioral disorders, and no pathological changes are noted in neuroradiological studies. Typical patterns are recorded on the EEG - normal basic activity and spikes of centrotemporal localization.

The most difficult differential diagnosis is rolandic epilepsy and complex partial paroxysms combined with impaired consciousness (Lerman, 1985). Difficulties in differential diagnosis are associated with the erroneous interpretation of speech disorders in rolandic epilepsy as a disorder of consciousness, as well as the impossibility of adequately assessing disorders of consciousness. occurring at night. In case of temporal and frontal epilepsy, the EEG reveals focal changes in the corresponding areas, and in case of rolandic epilepsy, spikes of centrotemporal localization are detected.

Treatment. Sulthiam has a satisfactory effect in the treatment of rolandic epilepsy (Doose et al, 1988). The dose of the drug is determined by the clinical manifestations of the disease. A spike-wave is required, as well as rolandic spikes localized in the centrotemporal or parietal areas. In addition, irregular “spike-wave” complexes with a frequency of 3/sec are recorded upon awakening or generalized slow “spike-wave” complexes.

Differential diagnosis should be made with a number of prognostically serious epileptic syndromes of childhood - Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, myoclonic-astatic epilepsy, as well as ESES syndrome. The most common diagnostic error is to consider atypical benign epilepsy as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. When making a differential diagnosis, it is necessary to take into account that Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is combined with a pronounced delay in neuropsychic development. Typical of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome are nocturnal tonic seizures with characteristic EEG patterns in the form of generalized slow “spike-wave” complexes with a frequency of 2-2.5/sec. An increase in the frequency of these complexes during sleep in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is an exception.

Myoclonic-astatic epilepsy, in comparison with atypical benign partial epilepsy, is characterized by a decrease in intelligence, there are no partial paroxysms, as well as slow spike-wave complexes during sleep.

Differential diagnosis of atypical benign partial epilepsy and ESES syndrome is based on the results of a polysomnographic study, which reveals typical patterns,

Treatment. The attacks usually disappear spontaneously. Since there is no decrease in intelligence in atypical benign partial epilepsy, combination anticonvulsant therapy is not recommended.

Benign partial epilepsy of childhood with occipital paroxysms

Benign partial epilepsy of childhood with occipital paroxysms was first described by Gastaut in 1950.

Genetic data. The role of genetic factors in the genesis of the disease is undeniable. Many patients have a hereditary history of epilepsy and migraine (Kuzniecky, Rosenblatt, 1987).

Clinical characteristics. The disease manifests itself mainly at the age of 2-8 years. At the same time, an earlier onset of the disease has been described. Gastaut (1992) noted that the disease can manifest itself at 5-17 years of age. The most typical manifestations of seizures in this form of epilepsy are visual disturbances - simple and complex visual hallucinations, illusions, amaurosis (Gastaut, 1992). These symptoms can be isolated or combined with convulsive paroxysms and transient hemiparesis. Often during attacks, headache, vomiting, turning of the head and eyes, and in some cases dysesthesia and dysphagia are noted (Kivity, Lerman, 1992). Attacks with prolonged impairment of consciousness have been described - for 12 hours (Kivity, Lerman, 1992). Panayiotopoulos (1989) noted that most often attacks occur at night and are accompanied by varying degrees of impairment of consciousness, vomiting, and deviation of the eyeballs.

Data from laboratory and functional studies. An EEG study records normal basic activity, high-amplitude (200-300 mV) unilateral or bilateral sharp waves or spike-wave complexes localized in the occipital regions. These changes disappear when you open your eyes. Hyperventilation and photostimulation do not affect the frequency and nature of epileptic EEG patterns. In 38% of cases, EEG studies also reveal generalized bilaterally synchronous “spike-wave” or “polyspike-wave” complexes.

Differential diagnosis should be made with simple and complex partial paroxysms, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, basilar migraine. Symptomatic partial epilepsies caused by structural damage to the occipital lobe are excluded on the basis of anamnesis, neurological status and neuroradiological examination, which, as a rule, reveal pathological changes. In symptomatic occipital epilepsies, compared with benign occipital epilepsies, opening the eyes does not block epileptic activity on the EEG.

Differential diagnosis with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is based on the presence of tonic seizures and EEG patterns characteristic of this syndrome. With basilar migraine, there is no epileptic activity on the EEG. Treatment. The first choice drug is carbamazepine.

Benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms. (Benign psychomotor epilepsy)

Many authors propose to consider benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms as an independent nosological form (Plouin et al, 1980; Dalla Bernardina et al, 1992).

Clinical characteristics. The disease manifests itself at the age of 2-9 years. The leading symptoms are attacks of fear. These paroxysms occur both during the day and at night. There were no differences in the clinical manifestations of daytime and nighttime paroxysms. The most typical signs of attacks in benign psychomotor epilepsy are paroxysms of fear: the patient suddenly becomes frightened, may cling to the mother, and sometimes swallowing and chewing automatisms occur. Laughter, groans, vegetovisceral disorders (hyperhidrosis, drooling, abdominal pain), and in some cases, speech stoppage (Dalla Bernardina et al, 1992) may also be observed. It should be emphasized that with this form of epilepsy, tonic, tonic-clonic, and atonic seizures are not observed.

Data from laboratory and functional studies. An EEG study reveals normal basic activity, rhythmic spikes or sharp-slow wave complexes with a predominant localization in the frontotemporal or parietotemporal regions (Dalla Bernardina et al, 1992). The frequency of epileptic patterns increases during slow-wave sleep.

Differential diagnosis should be made with complex partial paroxysms, Rolandic epilepsy, and nightmares.

Differential diagnosis of benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms and complex partial paroxysms is based on the criteria characteristic of this disease: onset in early childhood, normal intelligence, no changes in neurological status and in neuroradiological examination. In some cases, the differential diagnosis with Rolandic epilepsy is quite difficult. As is known, Rolandic epilepsy is often accompanied by speech impairment, guttural sounds, and drooling. A similar symptom complex is sometimes observed in benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms. Benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms is supported by pronounced psychomotor symptoms, which are always present in this disease.

Nightmares are very similar in clinical manifestations to seizures observed in benign psychomotor epilepsy. Compared to benign psychomotor epilepsy, nightmares occur exclusively at night, are characterized by frequent seizures and the absence of epileptic patterns on the EEG.

Treatment. Carbamazepine and phenytoin have a satisfactory effect in the treatment of benign psychomotor epilepsy. The prognosis of the disease is favorable.

Benign partial epilepsy with extreme (giant) somatosensory evoked potentials

Dawson in 1947 was the first to show that during somatosensory stimulation in individual patients with partial paroxysms and damage to somatosensory regions, high-amplitude (up to 400 mV) evoked potentials arise. These potentials are recorded on the side contralateral to stimulation. The highest amplitude of potentials is observed in the parasagittal and parietal areas. De Marco in 1971 published the results of a unique observation where touching the outer edge of the foot caused epileptic patterns on the EEG. Later, De Marco and Tassinari (1981) conducted a large study, analyzing 25,000 electroencephalograms from 1,500 children. It has been found that in 1% of children, sensory stimulation of the heels, toes, shoulders, arms or hips provokes giant somatosensory evoked potentials. It is noteworthy that 30% of the children examined suffered from epileptic paroxysms; in 15%, epileptic paroxysms arose later in life.

Clinical characteristics. Giant somatosensory evoked potentials occur between the ages of 4 and 6 years, most often in boys. Patients often have a history of febrile seizures. In most cases, attacks occur during the day. Most often, paroxysms manifest themselves as motor symptoms with a versive component, but generalized tonic-clonic seizures without previous focal disorders are also possible. Epileptic somatosensory potentials persist even after epileptic paroxysm. Attacks are relatively rare, 2-6 times a year. Intelligence does not suffer.

Data from laboratory and functional studies. At the age of 2.5-3.5 years, giant somatosensory evoked potentials appear; later, spontaneously occurring focal epileptic patterns are recorded on the EEG, observed first only during sleep and then during wakefulness. A year after the appearance of epileptic patterns on the EEG, clinically pronounced epileptic paroxysms appear.

Differential diagnosis. The most difficult differential diagnosis is with Rolandic epilepsy. The criteria that support the diagnosis of “benign partial epilepsy with giant somatosensory evoked potentials” are: intact facial muscles at the time of the attack, parasagittal and parietal localization of EEG patterns, spontaneous disappearance of epileptic somatosensory evoked potentials.

Treatment. Anticonvulsant therapy is ineffective. Epileptic seizures usually disappear spontaneously

Landau-Kleffner syndrome

The syndrome was first described by Landau, Kleffner in 1957. To date, about 200 cases of the disease have been described (Deonna, 1991).

Genetic data. According to Beaumanoir (1992), hereditary history of epilepsy is often observed.

Clinical characteristics. The disease manifests itself at the age of 3-7 years (Deonna, 1991). The triad of symptoms is aphasia, epileptic seizures, and behavioral disorders. Early symptoms are progressive speech impairment and verbal agnosia (Pauquier et al, 1992). Speech disorders are characterized by the appearance of speech perseverations, paraphasias, and jargon-aphasia. In most cases, there are no speech dysfunctions preceding the development of the disease (Echnne, 1990; Deonna, 1991). Aphasic disorders can have a fluctuating course with short-term remissions (Deonna et al, 1989). In 2/3-3/4 cases, epileptic paroxysms develop. Seizures are usually simple partial motor seizures. Less common are generalized tonic-clonic, hemiclonic or complex partial seizures and absence seizures. Atonic and tonic paroxysms are extremely rare. In 1/3 of patients, epileptic seizures are rare. Status epilepticus develops extremely rarely. One of the features of epileptic paroxysms in Landau-Kleffner syndrome is their nocturnal nature. The attacks are usually short. Behavioral disorders are manifested by aggression, hyperactivity, and autism.

Data from laboratory and functional studies. An EEG study records normal basic activity, focal or multifocal spikes, sharp waves, spike-wave complexes with predominant localization in the temporal, parieto-temporal or parieto-occipital regions. In some cases, with Landau-Kleffner syndrome, Rolandic spikes are detected on the EEG. A typical EEG pattern in Landau-Kleffner syndrome is electrical status epilepticus during slow-wave sleep (ESES) (Rodriguez and Niedermeyer, 1982).

Neuroradiological examination showed no pathological changes. Spectral positron emission tomography reveals decreased perfusion in the left middle frontal gyrus and right mediotemporal region (Mouridson et al, 1993). Positron emission tomography reveals metabolic disorders in the temporal region (Maquet et al, 1990), which persist even after clinical improvement. Differential diagnosis should, first of all, be carried out with diseases combined with aphasia - tumors, infections, metabolic disorders.

Treatment. Anticonvulsant therapy for speech disorders is practically ineffective (Marescaux et al, 1990). ACTH has a beneficial effect, however, its long-term use is impossible. Significant attention in complex therapy should be paid to speech therapy sessions in order to correct speech disorders.

<< Return to top

Continued >>

Diagnosis of partial epilepsy

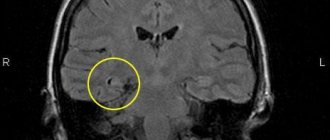

A correctly selected treatment program mainly depends on the timeliness and accuracy of diagnosing the disease. Incorrectly prescribed medications can aggravate the situation and intensify partial seizures of epilepsy. To diagnose dysfunction, magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalogram are used as research methods, with the help of which it is possible to determine the cause and source of the disease.

The final diagnosis can only be made by a specialist in the field of neurology or epileptology. After examining the patient, questioning him about complaints and information about symptoms, the doctor identifies the most likely causes of the disorders that have arisen, which are confirmed as a result of methodological studies.

Treatment of partial epilepsy

A high rate of successful outcome of therapy for idiopathic partial epilepsy is available at the Yusupov Hospital. In the neurology clinic, equipped in accordance with modern standards, specially trained doctors with extensive experience treat various types of pathologies associated with brain damage.

The main method of healing involves the use of medications. Drugs are selected individually based on the patient’s clinical picture, which includes symptoms, affected areas and other indicators. Correctly selected therapy will reduce the number and intensity of partial epileptic seizures. Highly qualified and extensive experience of specialists will allow you to achieve remission and return to a full life.

If conservative methods do not give a positive result, and the frequency of seizures is too high, then neurosurgery is resorted to. In the process, craniotomy is performed in the required area and further excision of everything that has a physical effect on the cerebral cortex. Such actions are called meningoencephalolysis. Less commonly, an operation is performed using the method of the English neurosurgeon Horsley, in which the affected areas are scooped out.

In case of scar damage to the membrane of the central organ, surgical intervention will not bring positive results. This is due to the fact that scars are renewed in large volumes.

The consequences of Horsley's operation may be paralysis of the limb, but the seizures will disappear. Paralysis eventually turns into monoparesis. Weakness in the limb remains for life, and attacks will return in the future.

In medical practice, the most preferable method is a conservative method of achieving a healing effect in a patient.