Types and classification

Symptoms of agnosia vary significantly depending on the damaged area of the cerebral cortex. Most often, one type of perception is affected, but the disease can affect several systems simultaneously. There are several main types of agnosia:

- visual (visual);

- auditory;

- olfactory - impaired perception of smells;

- tactile - change in response to touch;

- taste;

- other specific varieties.

Specialists at the Clinical Brain Institute have extensive experience working with patients with agnosia. It is important to promptly determine the type of disorder and begin maintenance therapy. In addition, the first signs of the disease may indicate serious pathologies of nervous activity.

Visual agnosia

This type of agnosia is characterized by a violation of the perception of information that enters the brain through the visual analyzer. Its symptoms may differ for each patient, depending on the type and location of the damage. So, we can distinguish several specific varieties:

- object-based (develops when the left occipital lobe is damaged) - the patient sees objects well, but has difficulty recognizing them;

- prozolagnosia (damage to the lower occipital region on the right) - inability to recognize even familiar faces;

- color (damage in the left occipital region) - difficulty identifying colors and shades, as well as determining their relationship with certain objects;

- weakness of optical representations (symmetrical damage to the occipital-parietal lobe) - inability to determine the color, shape and size of objects, imagine and describe them;

- simultaneous (pathology of the occipital region) - the patient can concentrate on only one object;

- Balint's syndrome (damage to the occipito-parietal region) - inability to direct the gaze and focus on objects that are in different directions, as well as difficulty identifying objects at near and far distances.

With visual agnosia, the normal functioning of the other sense organs is maintained, and no eye diseases are detected. After rehabilitation at the Clinical Institute of the Brain, the patient adapts to everyday life and can compensate for visual disorders using other analyzer systems.

Optical and optical-spatial agnosias

Patients experience impaired ability to determine the distance between objects and navigate in space. In this category, several specific types of agnosia can be distinguished:

- Depth agnosia (damage to the middle part of the occipital-parietal lobe) - difficulty determining the distance to objects, especially those located in the anterior direction from the patient;

- impaired stereoscopic vision (pathology in the left hemisphere) - inability to recreate a three-dimensional image;

- unilateral (damage to the opposite parietal region) - one half of the space falls out of the field of vision;

- Topographical orientation disorder (parietal and occipital regions) - difficulty finding familiar objects, including home address and objects in one’s own home.

Memory and attention are preserved in optical-spatial agnosia. The patient will need help with everyday life and with new tasks, but proper rehabilitation will allow him to experience minimal discomfort in everyday life.

Auditory agnosia

With this type of agnosia, the functions of the auditory analyzer are preserved. The patient may experience various auditory perception disorders, including:

- simple - decreased ability to characterize and identify familiar sounds;

- auditory-speech - impaired speech recognition, recognition of simple and familiar words;

- tonal - lack of understanding of voice timbre, emotional coloring and other aspects.

All types of auditory agnosia develop when the temporal lobe of the brain is damaged. If the patient is unable to recognize speech, he experiences difficulties in everyday life, while his memory, attention, and the functions of the visual and other analyzers compensate for the impairment.

Somatoagnosia

Somatoagnosia is a disorder in which the patient is unable to identify and recognize parts of his own body. These are complex perception disorders associated with damage to various parts of the right hemisphere of the brain. There are two main types of somatoagnosia:

- Anosognosia is a condition in which the patient denies the presence of an illness. This may be ignoring paralysis of limbs, blindness, or speech disorders.

- Autotopagnosia is a disorder of the ability to recognize individual parts of the body. The patient experiences difficulty when asked to point to an arm, leg, or face; in some cases, there is a feeling of a change in the size of parts of the body. This group also includes somatic allosthesia, in which the patient experiences a feeling of an increase in the number of limbs.

Signs of somatoagnosia may occur in attacks. Thus, in some patients they are harbingers of an epileptic attack, and with proper treatment they are practically invisible and do not cause inconvenience in everyday life. However, they can persist permanently.

Impaired awareness of space and time

This type is considered the rarest and is associated with damage to the occipital lobe of the cerebral cortex. The patient has difficulty determining the passage of time, as well as the speed of movement of any objects. Separately, there is akinetopsia - impaired ability to identify moving objects.

3. Symptoms and diagnosis

By definition, agnosia is the inability to identify an object or any of its physical characteristics. There are, accordingly, a lot of varieties and variants of agnosia. The main classes are visual, auditory, optical-spatial (as a rule, the perception of spatial depth along the central visual axis is most affected), simultaneous and somatoagnosia.

With simultaneous agnosia, the patient is unable to perceive a group of objects as a single whole, although each of the elements is perceived and identified adequately. A classic example is the lack of comprehension and understanding of the overall plot of the drawing while correctly recognizing individual characters, backgrounds and other objects. Disorders of this type are usually associated with disturbances of gaze and visual attention, the volume of which does not allow keeping several objects in the active field at the same time.

Visual agnosia also includes numerous specific forms: prosognosia (failure to recognize faces), color agnosia, Balint syndrome, Lissauer object agnosia, etc. Similarly, there are several types of acoustic and auditory agnosia (failure to recognize tone, intonation, sounds of a certain timbre, addressed speech, etc.).

Somatoagnosia is a large group of disorders associated with loss of perception of one’s own body and/or its individual parts.

Anosognosia is usually considered as a separate form - “denial of diagnosis”, when the patient has a complete lack of awareness of the disease (this can be either a somatic or mental illness, loss of any function or amputation of an organ) and, accordingly, criticism of one’s own condition and capabilities .

In the diagnosis of agnosia, first of all, the anamnesis, complaints, chronology and dynamics of the disorders that have arisen are carefully studied. Depending on the most likely causes, additional studies are prescribed: experimental psychological, MRI or CT, EEG, laboratory tests.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

Diagnostic methods

The Clinical Institute of the Brain has all the conditions for a full diagnosis of patients with agnosia. At the initial stage, it is important to determine exactly what difficulties the patient has with the perception of the environment. For this purpose, there are special tests, during which the patient is asked to describe objects, sounds, and point to parts of the body. After determining the type of disorder, it is important to conduct brain imaging using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. This research method will detect neoplasms, heart attacks, vascular damage and other anomalies that can cause agnosia.

Concepts about optical-spatial representations

A significant aspect of intellectual development is optical-spatial representations, which provide orientation in space, assimilation of knowledge, and mastery of various types of activities.

Spatial representations operate with images, the content of which is the reproduction and change of spatial properties and relationships of objects, namely: their shape, size, relative position of parts. Spatial relationships are understood as relationships between spatial objects or between spatial characteristics of these objects.

They are expressed in terms of:

ü about direction (“ backward - forward

", "

down - up

", "

right - left

");

ü about distance (“ far - close

»);

ü about their relationship (“ further - closer

»);

ü about location (“ in the middle

»);

ü about the extent of objects in space (“ low - high

», «

short - long

»).

According to I.S. Yakimanskaya [46], the main qualitative indicators of spatial representations are:

1. Type of operating with spatial images.

2. Breadth of operation (taking into account the graphic basis used).

3. Completeness of the image (the predominant reflection in it of the shape, size, spatial arrangement of objects).

4. The reference system used (spatial orientation “from oneself”, from an arbitrary reference point).

It must be said that significant indicators of the development of spatial concepts are the breadth of operation

and

completeness of the image

. The breadth of operation is defined as the degree of freedom to manipulate spatial images using a variety of graphic material. The completeness of the image is understood as correspondence to its real object, and characterizes the set of elements of the image, their connection and dynamism.

Optical-spatial representations are one of the more complex mental processes in structure.

Vision is of great importance in human life. This is the main sensory channel through which a person communicates with the outside world.

The human visual system is very complex.

In the human visual system, the following levels of signal processing should be emphasized

(T.V. Akhutina [2]).

The retina is located at the periphery.

During the development of the nervous system, the retina is formed at the initial stages of development, so there is every reason to consider the retina “a part of the brain located in the periphery.”

The next level of visual processing is located in the thalamus.

-

This is the external geniculate body

. Axons of neurons in the lateral geniculate body project to the cortex of the occipital pole of the cerebral hemispheres.

The highest level of processing of visual signals occurs in the associative fields of the cerebral cortex.

The human oculomotor system performs the following tasks:

1) leaves the image of the external world on the retina motionless at the moment of movement relative to this world;

2) identifies any objects in the external world, places them in the high-resolution retinal area (optic fovea, fovea) and tracks them with movements of the eyes and head;

3) spasmodic (saccadic) movements of the gaze in order to recognize (examine) the surrounding world.

The concept of “Saccades” is defined as rapid friendly deviations of the eyes in the initial phase of the tracking reaction, when the eye jump “captures” a moving visual target, and also during visual exploration of the external world.

In one case, both eyes move in the same direction with respect to the coordinates of the head, in another case, if a person alternately looks at close and distant objects, each of the eyeballs performs approximately symmetrical movements with respect to the coordinates of the head. In this case, the angle between the visual axes of both eyes changes: when fixating a distant point, the visual axes are almost parallel, and when fixing a close point, they converge. Such movements are called convergent

.

When looking at objects at different distances, eye movements are convergent (converging) and divergent.

If the neural system is not able to bring the visual axes of both eyes to one point in space, strabismus appears.

(A.R. Luria [19]).

When viewing all kinds of objects in the external world, the eyes make fast (saccades) and slow tracking movements. Thanks to slow tracking movements, the image of moving objects is held on the fovea (fovea). When viewing a well-structured image, the eyes make saccades alternating with gaze fixation. In the event that a person examines an image for some time, the recording of eye movements rather roughly recreates the contour and, to the greatest extent, informative details of the object in question. For example, when looking at a face, the mouth and eyes are most often recorded.

When conducting special experiments, it was revealed that at the moment of a saccade, visual perception is blocked (O.A. Krasovskaya [16]).

Several mechanisms for this phenomenon should be presented.

It is assumed that during a saccade over a highly structured background, intensity fluctuations at each point exceed the flicker fusion frequency.

Another mechanism that blocks visual perception during a saccade is central inhibition. At the moment when a moving object appears on the periphery of the visual field, it generates a reflex saccade, which can be accompanied by movement of the head.

The foundation of the neurophysiological mechanism of this reflex is motion detectors in the visual system.

Biologically, the reflex is justified by the fact that thanks to it, attention switches to another object that appears in the field of vision (Z.A. Melikyan [25]).

Higher gnostic visual functions are provided, first of all, by the work of the secondary fields of the visual system (18th and 19th) and the adjacent tertiary fields of the cerebral cortex. Secondary fields 18 and 19 are located on the outer convexital and inner medial surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres. They are characterized by a well-developed layer III, in which impulses are switched from one area of the cortex to another.

With electrical stimulation of the 18th and 19th fields, activation of a wide zone appears, which indicates broad associative connections of these areas of the cortex.

Thanks to studies conducted on humans, it has been established that with electrical stimulation of the 18th and 19th fields, complex visual images arise. These are no longer isolated flashes of light, but familiar faces, pictures, and sometimes some vague images. Basic information about the role of these areas of the cerebral cortex in visual functions was obtained from the clinic of local brain lesions.

Clinical observations indicate that various pathologies of visual gnosis result from lesions in these areas of the cortex and subcortical zones that adjoin them. These disorders are designated visual agnosia.

This term refers to disorders of visual perception that appear when the cortical structures of the posterior parts of the cerebral hemispheres are damaged and occur with the relative preservation of elementary visual functions (visual acuity, visual fields, color perception).

In all forms of agnostic visual disorders, elementary sensory visual functions remain relatively intact, that is, patients see quite well, they have normal color perception, and their visual fields are often preserved; in other words, they seem to have all the prerequisites in order to correctly perceive objects.

However, it is the gnostic level of the visual system that is disrupted in them. In some cases, patients, in addition to gnostic ones, also have sensory dysfunction. However, these are, as a rule, relatively subtle defects that cannot explain the severity and nature of disorders of higher visual functions.

The main types of optical-spatial disorders are:

· one-sided spatial agnosia;

· violation of topographic orientation;

· some manifestations of Balint's syndrome (inability to look at all objects that are in the field of vision due to disturbances in transference and gaze fixation, which usually leads to impaired orientation in space).

The formation of spatial representations begins already in the early stages of ontogenesis; they are basic for the development of many other mental processes (E.G. Simernitskaya [37]).

Assessment of the formation of spatial representations and spatio-temporal representations is carried out in the sequence that these levels do not simply “build on top” of each other in the course of development, but intersect in time, overlapping and “embedded” in each other, undergo mutual influences and, in general, closely interconnected in a way. Exactly as in the case of studying the voluntary regulation of mental activity, one should evaluate the “mature”, sufficiently formed level of spatial representations (in accordance with normative or typological concepts) and the closest to it “deficient” (unformed in whole or in part) level or, accordingly , sublevel (A.R. Luria [19]).

Treatment of agnosia

Treatment tactics are selected individually. The Clinical Brain Institute employs specialists with extensive experience in treating various types of agnosia. Only some cases require surgery - when tumors, aneurysms, abscesses and other structures are found that need to be removed. In other cases, treatment consists of compensating for lost functions and adapting the patient. For this purpose:

- classes with a speech therapist - special exercises strengthen neural connections and improve perception;

- occupational therapy;

- course of therapy with a neuropsychologist.

Doctors at the Clinical Institute of the Brain insist on full rehabilitation. It can last up to 10 months or more, but qualified medical care will significantly affect the patient’s well-being. Despite the fact that some changes in the structure of the cerebral cortex may be irreversible, it is possible to improve the patient’s quality of life and adapt it in everyday life.

Clinical Brain Institute Rating: 3/5 — 1 votes

Share article on social networks

4.Treatment

As follows from the above, it would be inappropriate to talk about the treatment of agnosia as such: in the vast majority of cases, the brain disease is treated and the causes that caused the recognition disorder are eliminated (to the extent possible). Thus, based on the results of a diagnostic examination, stimulants of cerebral circulation and tissue nutrition, a rehabilitation course with the participation of a psychologist and/or other specialized specialists may be prescribed. The prognosis also depends on the etiopathogenesis; extreme cases are spontaneous self-healing and persistent, treatment-resistant agnosia with corresponding social maladjustment.

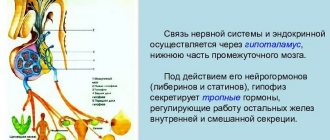

Localization

Optical-spatial agnosia occurs when there is damage to the superior parietal and parieto-occipital parts of the cortex of the left or right hemispheres of the brain, which carry out the complex interaction of several analyzer systems (visual, auditory, tactile, vestibular). Optical-spatial agnosia is especially severe in cases of symmetrical bilateral lesions. However, even with unilateral lesions, these disorders are also quite clearly expressed.[1]

The basis of optical-spatial agnosia, and the basis of other manifestations of damage to the parietal system of the brain, is a violation of two factors: somatosensory and spatial (and quasi-spatial) analysis and synthesis.[2] A.R. Luria considered optical-spatial disorders as a defect in the synthesis of information from various modalities.[3]

Manifestations

According to E. D. Chomskaya [1], in patients with optical-spatial agnosia, orientation in spatial features of the environment and images of objects is disturbed. These are signs such as left-right orientation, orientation in upper-lower coordinates (in rough cases). Such patients do not understand the geographical map, their orientation in the cardinal directions is impaired.

In patients with opto-spatial agnosia, spatial abilities are impaired, including the ability to draw (while maintaining the ability to copy images). They do not know how to convey spatial characteristics of objects in a drawing (further-closer, more-less, left-right, top-bottom). In some cases, the general scheme of the drawing is disrupted - the patient depicts parts of the object separately from each other and cannot connect them. Violation of the pattern occurs more often with damage to the posterior parts of the right hemisphere[1].

In some cases (usually in the case of lesions in the right hemisphere), unilateral optical-spatial agnosia

(ignoring the left half of the space). In this case, patients depict only one side of the object (usually the right) or grossly distort the image of one of them (usually the left)[1].

Optical-spatial impairments can affect reading skills. In these cases, difficulties arise in reading asymmetrical letters that have “left-right” features (k, m, p, h, etc.)[1].

In patients with this form of agnosia, the praxis of posture is often disrupted (visual afferentation of spatially organized movements is disrupted). This manifests itself in the fact that they cannot copy the pose because they do not know how to position the hand in relation to their body due to a violation of the perception of spatial relationships. This disorder is diagnosed using Head tests. They also have difficulties in everyday motor acts that require spatial orientation (they cannot make the bed or get dressed - apraxia of dressing).

Combinations of visuospatial (agnosia) and motor-spatial disorders (apraxia) are called apraktoagnosia.

I. Tonkonogiy and A. Pointe distinguish the following types of optical-spatial agnosia [4]:

- Visual disorientation in the environment

- difficulties in visually recognizing the spatial relationships of objects in the context of the immediate environment perceived by the subject.

Depth agnosia

is an impairment in the ability to localize objects in three-dimensional space, especially in the sagittal plane. Patients have difficulty determining the absolute distance to an object and the relative localization of two objects (which object is closer, which object is higher); there may be errors in counting the number of objects located on the same projection line. In some cases, the localization of objects in the frontal (coronal) plane is disrupted, which causes difficulty in perceiving the location of an object to the right or left of the observer. Such patients make mistakes when they try to touch an object, touch it while walking, or compare the size of two visible objects. All of the above causes a violation of orientation in three-dimensional space. There are cases when orientation in real three-dimensional space is preserved, but there are disturbances in the processing of visual-spatial information in two-dimensional space (on paper). This is due to a violation of the assessment of spatial properties. - impairment of stereoscopic vision

(a rare type of impairment). In some cases, accompanied by depth agnosia - visual alloesthesia

(optical alloesthesia)

is

the doubling or tripling of an object in the visual field

- loss of a person’s ability to move in space to a specific destination, impaired recognition of the properties of the surrounding space or topographical landmarks. Topographic disorientation is often accompanied by prosopagnosia. There is still debate about the differences between topographic agnosia and topographic apraxia. Difficulty separating topographical orientation from apraxia (internal navigation)

,

because its clinical manifestations look like disorders of movement along a certain route to a goal. This is similar to the disturbance of hand movements when drawing in the case of apraktoagnosia.

- topographical disorientation in real space: in real familiar space.

Patients lose the ability to navigate their own home, find a previously well-known road, or return home from a walk around the neighborhood. In more serious cases, the patient cannot find a toilet, his room or a bed in his own home or hospital. Sometimes the direction is chosen correctly, but the ability to navigate at certain points on the route may be impaired. The patient may reach a place where he needs to turn, but he cannot understand where he came from and where he needs to turn next. In such cases, patients try to use some features of objects, since object recognition usually remains intact.

- the inability to determine one’s location in a general topographic coordinate system. The patient is unable to determine his current location: room, building, area, city, country. These disorders may also be one of the important signs of decreased intelligence with significant memory impairment.

-

impaired ability to describe or draw plans of the area.

They manifest themselves in violations of the designation of north, south, west and east, in difficulties in understanding topographic coordinates and indicating the relative location of geographical objects. Orientation to the actual map may be impaired, and if the map is not rotated correctly, the patient may have difficulty finding his or her position on the map. Difficulties arise when patients try to draw or describe a road, remember the spatial arrangement of city streets, or draw or describe the plan of their own apartment or room. In many cases, these disturbances may not be accompanied by disorientation in real space. Also, if orientation in real space is impaired, the ability to describe or draw the terrain may remain intact.