Partial epilepsy is a type of disease that occurs when there is a limited area of activity in the brain. Accompanied by focal or secondary generalized seizures. Accounts for 82% of all variants of epileptoid syndrome. In 70% of cases it is formed against the background of injuries and other pathologies. In 75% of patients, it debuts in childhood.

The specialists at the Leto clinic have extensive practical experience in treating epilepsy. Registration is carried out by telephone.

general information

Epilepsy attacks have been known to people for a very long time. It was either mistaken for demonic possession or associated with a person’s special talent. Today, one or another form of pathology is observed in 10 people out of 1000. Symptoms can occur in newborns and the elderly, in men and women with the same frequency. Moreover, similar processes occur in the central nervous system of some animals, for example, dogs.

The main mechanism for the occurrence of attacks is the synchronization of the work of all nerve cells in a certain area. It is called an epileptogenic focus and determines the set of symptoms and their severity. Contrary to popular belief, the disease is not limited to seizures with loss of consciousness. There are a large number of variants of seizures with varied symptoms, depending on the area of the brain in which the pathological focus occurs.

Make an appointment

Description and types of parietal epilepsy

Parietal epilepsy is a rare disease, its share in surgical practice is 6%.

The disease can debut at any age. There are no gender preferences observed in parietal epilepsy.

The etiology of the disease can be symptomatic, cryptogenic or idiopathic.

The attacks last several seconds, less often – up to 2 minutes. The attacks are repeated frequently, sometimes every day, and they can be grouped into clusters. During the day, the likelihood of an attack is higher.

Causes

The functioning of the brain is a complex process that requires the constant interaction of many structures. A failure at any level can cause the formation of an epileptogenic focus. Among the most common causes of epilepsy in adults and children are:

- heredity;

- traumatic brain injuries;

- acute or chronic intoxication, especially alcoholism;

- infectious lesions of the brain or its membranes (encephalitis, meningitis);

- acute and chronic cerebrovascular accidents, including strokes;

- malignant and benign tumors in the cranial cavity;

- birth injuries;

- parasites that develop in brain structures: echinococcus, pork tapeworm;

- neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, Pick's disease);

- hormonal imbalances, especially lack of testosterone;

- metabolic disorders, etc.

There are cases when the cause of epilepsy cannot be identified. In this case, the disease is called idiopathic.

Diagnosis of focal epilepsy

Approximately 65 million patients worldwide are diagnosed. It begins to develop most often in childhood, adolescence or old age. The disease is diagnosed in men more often than in women. It is impossible to cure completely, but its course can be controlled with the help of medications and various techniques.

The occurrence of partial paroxysm is a serious manifestation that requires urgent medical intervention. First of all, the doctor will conduct a visual examination and interview the patient to identify visible symptoms of the disease. The following should be excluded from the list of causes of defeat:

- Focal cortical dysplasia is a disorder of neuronal proliferation and the architecture of the cerebral cortex.

- Vascular malformation is a violation of the intrauterine development of the brain, accompanied by a violation of its structure and functions;

- Tumors are both benign and malignant, and in both cases they threaten serious health problems.

The neurologist must identify the sequence, timing, frequency and strength of the attacks. The information obtained allows us to determine the location of the lesion with maximum accuracy.

To obtain confirmation of the diagnosis, the patient first needs to contact a specialist - a neurologist or epileptologist. The patient is prescribed the following diagnostic tests:

- Electroencephalography is a technique that allows you to determine epiactivity in the interval between attacks.

- An EEG with provocative tests is prescribed if the information obtained during the first study is insufficient. Sometimes daily monitoring of cortical activity is carried out.

Extremely informative data is obtained if the electrodes are installed under the skull. The method is called subdural corticography, but due to the complexity of its implementation, it is little used in ordinary medical practice.

To identify quantitative and qualitative indicators of the morphology of changes, several basic research methods are used:

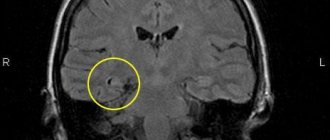

- MRI or magnetic resonance imaging with a slice thickness of no more than 2 mm. With the symptomatic type of the disease, changes of a different nature will be observed on the tomogram, including atrophy and lesions. If none are found, most likely the patient has an idiopathic or cryptogenic form of epilepsy.

- PET or positron emission. The study allows you to determine hypermetabolic processes in the affected area.

- SPECT or single photon emission computed tomography. In this case, it is possible to determine the lack of blood supply to the lesion.

Types and symptoms

Epilepsy is multifaceted and multifaceted; its symptoms are not limited to seizures. The most common classification is depending on the severity of attacks and their main manifestations.

Aura (harbingers)

Many epileptic seizures begin with an aura. This is the name given to a complex of specific sensations that occurs shortly before a seizure. Manifestations of an aura can be completely different: paresthesia (pathological sensations), a specific taste in the mouth, auditory, visual or olfactory hallucinations, etc. Before the appearance of an aura, a person often begins to experience causeless anxiety and internal tension.

Partial (focal) seizures

These conditions occur when a small area of the brain is involved in pathological overexcitation.

Simple partial seizures are characterized by preserved consciousness and last only 1-2 minutes. Depending on the location of the pathological focus, a person feels:

- sudden change of mood for no apparent reason;

- small twitching in a certain part of the body;

- feeling of déjà vu;

- hallucinations: lights before the eyes, strange sounds, etc.;

- paresthesia: a feeling of tingling or crawling in any part of the body;

- difficulty pronouncing or understanding words;

- nausea;

- change in heart rate, etc.

Complex attacks are characterized by more severe symptoms and often affect consciousness and thinking. Human can:

- lose consciousness for 1-2 minutes;

- there is no point in looking into emptiness;

- scream, cry, laugh for no apparent reason;

- constantly repeat any words or actions (chewing, walking in a circle, etc.).

Typically, during a complex seizure and for some time after it, the patient remains disoriented for some time.

Generalized seizures

Generalized seizures are one of the classic signs of epilepsy that almost everyone has heard of. They occur if the epileptogenic focus has spread to the entire brain. There are several forms of seizures.

- Tonic convulsions. The muscles of most of the body (especially the back and limbs) simultaneously contract (come to tone), remain in this state for 10-20 seconds and then relax. Such attacks often occur during sleep and are not accompanied by loss of consciousness.

- Clonic convulsions. Rarely occur in isolation from other types of attacks. Manifested by rhythmic rapid contraction and relaxation of muscles. The movement cannot be stopped or delayed.

- Tonic-clonic seizures. This type of attack is called grand mal, which means “great illness” in French. The attack is divided into several phases: precursors (aura);

- tonic convulsions (20-60 seconds): the muscles become very tense, the person screams and falls; at this time his breathing stops, his face becomes bluish, and his body arches;

- clonic convulsions (2-5 minutes): the muscles of the body begin to contract rhythmically, the person thrashes on the floor, foam is released from the mouth, often mixed with blood due to a bitten tongue;

- relaxation: convulsions stop, muscles relax, involuntary urination or defecation often occurs; consciousness is absent for 15-30 minutes.

After the end of a generalized seizure, a person remains for 1-2 days feeling overwhelmed, problems with coordination of movements and fine motor skills. They are associated with cerebral hypoxia.

- Atonic attacks. They are characterized by short-term muscle relaxation, accompanied by loss of consciousness and falling. The attack lasts literally 10-15 seconds, but after it ends the patient does not remember anything.

- Myoclonic seizures. They manifest themselves as rapid twitching of the muscles of individual parts of the body, usually the arms or legs. The seizure is not accompanied by loss of consciousness.

- Absence seizures. The second name for attacks is petit mal (minor illness). This symptom of epilepsy occurs more often in children than in adults and is characterized by a short-term loss of consciousness. The patient freezes in place, looks into emptiness, does not perceive speech addressed to him and does not react to it. The condition is often accompanied by involuntary blinking of the eyes, small movements of the hands or jaws. The duration of the attack is 10-20 seconds.

Pediatric epilepsy

Childhood epilepsy has many masks. In newborns, it can be manifested by periodic muscle contractions that do not resemble seizures, frequent tilting of the head back, poor sleep and general restlessness. Older children may suffer from classic seizures and absence seizures. Partial seizures most often occur:

- severe headaches, nausea, vomiting;

- short periods of speech disorder (the child cannot utter a single word);

- nightmares followed by screams and hysterics;

- sleepwalking, etc.

These symptoms are not always a sign of epilepsy, but they should serve as a reason for an urgent visit to the doctor and a full examination.

Epilepsy in childhood

Part 4. Read the beginning of the article in No. 6 and 10, 2014

Epilepsy in preschool children (4–6 years old)

Preschool children are characterized by the onset of idiopathic partial epilepsy with frontal paroxysms, benign occipital epilepsy with an early onset (Panagiotopoulos syndrome), as well as Landau-Kleffner syndrome.

Idiopathic partial epilepsy with frontal paroxysms

The disease was first described by A. Beaumanoir and A. Nahory (1983). The age of patients at the onset of epilepsy is 2–8 years. This type of epilepsy accounts for about 11% of cases of all idiopathic focal epilepsies. The disease manifests itself in the form of several types of seizures: daytime (complex partial, motor automatisms, sometimes absence-like) and nighttime (hemifacial motor seizures, versive, sometimes with “post-crisis” deficit and/or secondary generalized seizures). The frequency of attacks varies from 1 episode per month to 1 attack per few weeks (the duration of the active period of the disease ranges from 1 year to 6 years). EEG data are quite heterogeneous and do not have a single specific pattern (in some patients, EEG changes are comparable to those in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal peaks; others have only focal slow activity; intermittent frontal discharges are recorded in the ictal period). The prognosis of the disease is quite favorable (spontaneous remission). A transient decrease in cognitive functions (short-term memory, operational functions, etc.) is observed during the active period of the disease; then they gradually recover [3–6].

Benign occipital epilepsy with early onset (Panagiotopoulos syndrome)

One of the benign occipital epilepsies of childhood. The disease debuts between the ages of 1 and 14 years (peak incidence at 4–5 years of age); occurs approximately 2 times more often than the Gastaut variant. Autonomous nocturnal attacks are characteristic; Due to autonomic symptoms and nausea, seizures are poorly recognized. In the early stages of the disease, eye deviation and behavioral disorders are observed (in 50% of cases, attacks can become convulsive in nature). The duration of attacks is 5–10 minutes; in 35–50% of patients they progress to autonomic focal status epilepticus (sometimes with secondary generalization). EEG records peaks or paroxysmal discharges. Two thirds of patients have at least one EEG study with signs of occipital paroxysms (most often occipital peaks); the remaining third of patients have only extra-occipital peaks or short generalized discharges. In approximately 33% of cases in children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome, multifocal peaks in two or more cerebral areas are recorded on the EEG (single peak foci are considered rare). The prognosis for Panayiotopoulos syndrome in terms of long-term remission and cognitive functions is relatively favorable. Treatment of early-onset benign occipital epilepsy is predominantly aimed at controlling seizures in the acute phase (diazepam) [3–6].

Landau–Kleffner syndrome (acquired epileptic aphasia)

The overwhelming majority of cases of the disease occur at the age of 4–5 years, although the disease (acquired aphasia and epileptiform discharges in the temporal/parietal areas of the brain) can debut earlier - in the second or third year of life. The cause of this relatively rare condition is unknown. Landau–Kleffner syndrome is characterized by loss of speech skills (impressive and/or expressive aphasia). These speech disorders, as well as auditory agnosia, appear in children who have not previously had deviations in psychomotor and speech development. Concomitant epileptic seizures (focal or generalized tonic-clonic seizures, atypical absences, partial complex, rarely myoclonic) are recorded in 70% of patients. Some children have behavioral disorders. Otherwise, the patients’ neurological status usually has no significant disturbances. A specific EEG pattern is not typical for Landau–Kleffner syndrome; epileptiform discharges are recorded in the form of repeated peaks, sharp waves and peak-wave activity in the temporal and parieto-occipital regions of the brain. Epileptiform changes in sleep state are intensified or observed exclusively during sleep. Although the prognosis of Landau–Kleffner syndrome is relatively favorable, the onset of the disease before the age of 2 years is always associated with an unfavorable outcome in acquiring and/or restoring speech communication skills [3–5, 9].

Epilepsy in school-age children and adolescents

Upon reaching school age, children and adolescents are at risk of exposure to a whole group of age-dependent epilepsies, among which the most relevant are childhood absence, benign with centrotemporal peaks, benign occipital (Gastaut variant), juvenile absence, juvenile myoclonic (Jantz syndrome) and a number of other forms of the disease.

Pediatric absence epilepsy (pycnolepsy)

The peak onset of the disease occurs in early school age (about 7 years), although childhood absence epilepsy can debut from 2 to 12 years. It rarely debuts before the age of 3. Refers to idiopathic forms of the disease; all cases are considered genetically determined (autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance). Childhood absence epilepsy is characterized by frequent repeated absence attacks (up to several hundred per day). In this case, absence seizures are the only or leading type of epileptic seizures; the likelihood of generalized tonic-clonic seizures is significantly lower than with juvenile absence epilepsy. Diagnosis of childhood absence epilepsy is carried out based on clinical manifestations and EEG data (a typical EEG pattern is bursts of generalized high-amplitude peak-wave activity with a frequency of 3 per 1 sec, suddenly appearing and gradually stopping). The prognosis for childhood absence epilepsy is relatively favorable [3, 5, 6].

Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal peaks (rolandic epilepsy)

Described by P. Nayrac and M. Beaussart (1958). In the age group 0–15 years, it occurs with a frequency of 5–21 per 100 thousand (8–23% of all cases of epilepsy), being the most common form of idiopathic epilepsy in children. The age of children at the time of the debut of rolandic epilepsy varies from 3 to 14 years (peak - 5–8 years). Cases of the disease in patients under 2 years of age are extremely rare. The disease manifests itself in the form of nocturnal tonic-clonic seizures with a partial (focal) onset, as well as daytime simple partial ones (emanating from the lower cortical regions - the region of the central Rolandic sulcus). The frequency of attacks is usually low. Rolandic epilepsy is characterized by a specific somatosensory aura (pathological sensations in the buccal-oral area), as well as hypersalivation, speech arrest, tonic-clonic or tonic convulsions of the facial muscles. The patient does not lose consciousness during the attack. EEG data is characterized by the presence of peak-wave complexes localized in the central temporal regions. In the interictal period, patients' EEG records specific complexes in the form of high-amplitude 2-phase peaks accompanied by a slow wave. Rolandic peaks are localized in one or both hemispheres (isolated or in groups: in the middle temporal - T3, T4, or central - C3, C4 areas). By the time the disease debuts, the psychomotor development of children is normal. Subsequently, the disease is characterized by an almost complete absence of neurological and intellectual deficits. Many patients go into remission during adolescence; A small proportion of children have impairments in cognitive functions (verbal memory), as well as various speech disorders and decreased academic performance (at school) [3–6, 9].

Benign occipital epilepsy with late onset (Gastaut variant)

Focal form of idiopathic epilepsy of childhood (Gastaut syndrome) with a later onset than Panayiotopoulos syndrome. The disease onsets between ages 3 and 15 years, but peaks at approximately 8 years of age. Characterized by short-duration attacks with visual disturbances (simple and complex visual hallucinations), complete/partial loss of vision and illusions, deviation of the eyes, followed by clonic convulsions involving one side of the body. Up to 50% of patients experience migraine or migraine-like cephalgia after the attack. EEG data resemble those in Panayiotopoulos syndrome: in the interictal period, normal main activity of the background recording is recorded in combination with epileptiform unilateral or bilateral discharges in the occipital leads in the form of peak-wave complexes (high-amplitude biphasic peaks with a main negative phase followed by a short positive phase) in combination with negative slow-wave activity. When the patient opens his eyes, epileptiform activity disappears, but resumes again 1–20 seconds after closing the eyes. The prognosis for benign occipital epilepsy with late onset (Gastaut variant) is relatively favorable, but, due to the possible pharmacoresistance of the disease, it is ambiguous [3–5, 9].

Juvenile (youthful) absence epilepsy

The juvenile variant of absence epilepsy belongs to the idiopathic generalized forms of the disease. Unlike childhood absence epilepsy, the disease usually debuts at puberty, pre- or post-puberty (9–21 years, usually 12–13 years). The disease manifests itself as typical absence seizures, myoclonus, or generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The likelihood of a debut in the form of generalized tonic-clonic seizures in juvenile absence epilepsy is slightly higher (41% of cases) than in childhood absence epilepsy. The EEG pattern characteristic of this type of epilepsy has the form of peak-wave activity with a frequency of 3 Hz - symmetrical and bilaterally synchronized. Polypeak-wave activity, which occurs in some patients, should be alarming in terms of transformation of the disease into juvenile myoclonus epilepsy. The prognosis is relatively favorable - there is a high probability of remission in late adolescence [3–6, 9].

Juvenile (youthful) myoclonus epilepsy (Jantz syndrome)

The disease was described by D. Janz and W. Christian (1957) as one of the subtypes of idiopathic generalized epilepsy (another name: “impulsive petit mal”). Usually debuts at the age of 8–26 years (usually at 12–18 years). The hallmark of the disease is myoclonic seizures. Isolated myoclonic twitching in the upper extremities is characteristic, especially soon after awakening. Most children have generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and about a third of patients have absence seizures. Seizures are often triggered by sleep deprivation. Myoclonic seizures are accompanied by short bursts of generalized spike-wave or polyspike-wave complexes during EEG [3–5, 9].

Familial temporal lobe epilepsy

This genetically heterogeneous syndrome is characterized by relatively benign simple or complex partial (focal) seizures with a pronounced mental or autonomic aura. The disease usually debuts in the second (about 11 years) or early third decade of life (more often in adult individuals). Usually occurs against the background of normal development of the central nervous system. MRI of the brain does not reveal any pathological structural changes in the hippocampus or temporal lobes. EEG data allows recording epileptiform activity in the medial and/or lateral areas of the temporal lobes. Seizures in familial temporal lobe epilepsy are often easily controlled medically with traditional antiepileptic drugs [3–6, 9].

Mesial temporal epilepsy

It often debuts in adolescents and is manifested by limbic seizures. In typical cases, in patients with a history of febrile convulsions, temporal lobe seizures occur after a seizure-free interval, which at first respond well to drug control. Subsequently, in adolescence or upon reaching adulthood, relapses of the disease are observed. MRI of the brain may show hippocampal sclerosis in patients, which is considered a key feature of this form of epileptic syndrome. All limbic seizures are more or less refractory to pharmacotherapy [3, 5].

Familial mesial temporal epilepsy

This genetically determined heterogeneous epileptic syndrome was described by P. Hedera et al. (2007). The disease debuts at different ages, but most often in the second decade of life. In contrast to the mesiotemporal epilepsy described above, children usually have no history of febrile seizures. In most cases, patients experience simple focal seizures with the appearance of déjà vu, periodically associated with stupor or nausea, in other cases - complex partial seizures with changes in consciousness and freezing; Secondary generalized attacks occur less frequently. In some patients, MRI shows no signs of hippocampal sclerosis or other abnormalities of cerebral structures. There are no pathological changes in EEG data in approximately half of the patients. Less than half of cases of familial mesial temporal epilepsy require treatment with antiepileptic drugs [3, 5, 6].

Partial (focal) autosomal dominant epilepsy with auditory stimuli

This form of the disease is actually one of the subtypes of lateral temporal lobe epilepsy; it is also known as telephone epilepsy. The disease debuts at the age of 8–19 years (most often in the second decade of life). Partial autosomal dominant epilepsy with auditory stimuli is characterized by auditory disturbances (the patient feels undifferentiated sounds and noises), auditory hallucinations (changes in the perception of volume and/or pitch of sounds, voices “from the past,” unusual singing, etc.). In addition to auditory disorders and hallucinations, this form of the disease is characterized by various autonomic disorders, pathological motor activity, as well as numerous sensory and mental disorders of varying severity. During the interictal period, EEG may show paroxysmal activity in the temporal or occipital leads (or be completely absent) [3, 5, 9].

Epilepsy with grand mal attacks on awakening

In children, the onset of seizures with this idiopathic generalized epilepsy mainly occurs in the second decade of life. In its manifestations, the disease is somewhat reminiscent of juvenile myoclonus epilepsy of Janz. The development of tonic-clonic seizures occurs exclusively or predominantly after awakening (> 90% of cases) or in the evening during the period of relaxation. Seizures are caused by sleep deprivation. In contrast to Janz myoclonus epilepsy, myoclonus and absence seizures are rarely observed in patients with this form of epilepsy. EEG makes it possible to register generalized peak-wave activity and signs of photosensitivity (the latter are not always present) [3–6, 9].

Unferricht–Lundborg disease (Baltic or Finnish myoclonus epilepsy)

This rare form of epilepsy begins in children between the ages of 6 and 13 years (usually around 10 years of age). Its manifestations resemble Ramsay Hunt syndrome. The first symptoms are seizures. Myoclonus occurs after 1–5 years; they are noted mainly in the proximal muscles of the limbs, are bilaterally symmetrical, but asynchronous. Myoclonus is induced by photosensitivity. The severity of myoclonus gradually increases. Subsequently, a progressive decline in intelligence occurs (to the point of dementia). In the later stages of the disease, patients develop signs of cerebellar ataxia [3, 5, 6].

Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type III

This disease is also known as “progressive epilepsy with mental retardation” or “northern epilepsy”. It is a representative of neurodegenerative storage diseases. Debuts in preschool (5–6 years) or school (7–10 years) age. It is characterized by manifestation in the form of generalized seizures (tonic-clonic seizures) or complex partial (focal) seizures. As patients reach puberty, the frequency of attacks decreases significantly. In adulthood, it is possible to achieve complete remission of attacks [3, 5, 6, 9].

Catamenial (menstrual) epilepsy

With this type of epilepsy, which is not an independent nosological form, the occurrence of attacks is associated with phases of the menstrual cycle, influenced by numerous endogenous and exogenous factors (presumably cyclic changes in the content of sex hormones in the body, disturbances in water and electrolyte balance, the influence of the full moon, fluctuations in the level of antiepileptic drugs in blood). The disease is characterized by a clear dependence on the menstrual cycle. According to some data, generalized forms of the disease, juvenile myoclonus epilepsy and juvenile absence epilepsy occur with almost equal frequency among teenage girls. Generalized convulsive paroxysms usually tend to increase in frequency in all patients with catamenial epilepsy [3, 5, 9].

Epilepsy with an undifferentiated age range of onset

In some epilepsies, the age-related features of onset are considered unclear. The main ones are discussed below.

Epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures

The disease most often occurs at the age of 5–10 years and is characterized by clinical manifestations in the form of absence seizures, combined with intense rhythmic bilateral clonic or (less often) tonic convulsive twitching of the proximal muscles of the upper and lower extremities, as well as the head. It is usually combined with mental development disorders and is characterized by pharmacoresistance, which determines the unfavorable prognosis of the disease. The diagnosis of epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures is considered to be made in patients who meet the criteria for childhood absence epilepsy, but the absence seizures must be accompanied by myoclonic jerks. Treatable with valproate, ethosuximide or lamotrigine (the combination of valproate with lamotrigine or ethosuximide is considered more effective); Cancellation of treatment is possible no earlier than 2 years after achieving complete remission (clinical and instrumental) [3–5, 9].

Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus

Refers to genetically determined epileptic syndromes and represents several types of epilepsy (GEFS+ type 1, GEFS+ type 2, GEFS+ type 3, GEFS+ type 5, FS with afebrile seizures and GEFS+ type 7). It is believed that in GEFS+, first described in 1997, a diagnosis of epilepsy is not necessary. Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus usually occurs in children aged 1–6 years. The average age of children at the time of GEFS+ debut is about 12 months. The disease manifests itself in the form of febrile convulsions against a background of fever and in the form of other epileptic paroxysms. In addition to recurrent febrile seizures (classic tonic-clonic), GEFS+ is characterized by the presence of afebrile seizures; The clinical picture of the disease may include absence seizures, myoclonus, myoclonic-astatic and atonic seizures. In most cases, GEFS+ phenotypes turn out to be benign (once adolescence is reached, attacks are often eliminated). Upon reaching adulthood, some patients may experience rare attacks (under the influence of stress and sleep deprivation). Children with GEFS+ do not generally require antiepileptic pharmacotherapy, although some authors recommend the use of benzodiazepines (acutely or preventively). Valproate is indicated only in cases where GEFS+ persists after 6 years of age, and lamotrigine is used in cases resistant to valproate [3, 5, 6, 9].

Benign psychomotor epilepsy of childhood, or benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms

Localization-dependent focal form of epilepsy. The etiology can be cryptogenic, familial or symptomatic. It occurs in children of all ages (7–17 years). Benign psychomotor epilepsy is characterized by recurrent seizures originating from lesions in the temporal lobe, most often from the mesial region. The disease is characterized by a wide range of mental phenomena, including illusions, hallucinations, dyscognitive states and affective disturbances. Most complex partial (focal) seizures originate in the temporal lobes. This form of epilepsy is characterized by monoform seizures, onset in childhood, and age-dependent disappearance of all clinical and EEG manifestations [3–5, 9].

Atypical benign partial epilepsy, or pseudo-Lennox syndrome

Mostly observed in children aged 2–6 years (74% of observations). At the time of the onset of the disease, approximately a quarter of children show signs of delayed speech development. In boys it debuts earlier than in girls. Characterized by generalized minor seizures (atonic-astatic, myoclonic, atpic absence seizures). A distinctive feature of the disease is the extremely pronounced activation of epileptic seizures during sleep. The main type of seizures is minor generalized (67%), with 28% of patients having simple partial seizures of the orofacial region (or generalized tonic-clonic seizures originating from the orofacial region). In addition to this, the following types of seizures occur with varying frequency in children (in descending order): generalized tonic-clonic (44%), partial motor (44%), unilateral (21%), versive (12%), focal atonic ( 9%), complex partials (2%). A small proportion of patients experience the phenomenon of epileptic negative myoclonus. The EEG pattern resembles that of rolandic epilepsy (focal sharp slow waves and peaks), but is characterized by generalization during sleep. With regard to seizures, the prognosis of the disease is favorable (all patients are “seizure-free” by the age of 15), but children often experience intellectual deficits of varying severity (about 56% of observations) [3, 5].

Aicardi syndrome

A type of epileptic syndrome associated with malformations of the central nervous system (cortical organization disorders, schizencephaly, polymicrogyria. The syndrome described by J. Aicardi et al. (1965) includes agenesis of the corpus callosum with chorioretinal disorders and is characterized by infantile flexor spasms. Affects almost exclusively girls, although known 2 cases of registration of the disease in boys with an abnormal genotype (both children had two X chromosomes).In addition to epileptic manifestations, the following pathological changes are typical for Aicardi syndrome: chorioretinal lacunar defects, complete or partial agenesis of the corpus callosum, malformations of the thoracic spine, microphthalmia , coloboma of the optic nerve, etc. Clinically, Aicardi syndrome is characterized by infantile spasms (often with an early onset) and partial (focal) epileptic seizures (in the first days or weeks of life), as well as severe retardation in intellectual development. Epileptic seizures with Aicardi syndrome are almost always turn out to be pharmacoresistant. The prognosis of the disease is unfavorable [3, 5–7, 9].

Electrical status epilepticus slow-wave sleep (ESES)

This type of epilepsy is also known by another name (continuous peak-wave discharge epilepsy during slow-wave sleep, CSWS). It is considered idiopathic epilepsy and debuts in children from about 2 years of age. Clinically characterized by focal, generalized tonic-clonic and/or myoclonic seizures that occur while awake or asleep (not always observed). Subsequently, the disease leads to speech development disorders, behavioral disorders, and cognitive dysfunctions of varying severity. The diagnosis is established on the basis of EEG data during sleep (a specific pattern in the form of continuous generalized peak-wave activity); in this case, epileptiform activity should occupy 85–100% of the total duration of the slow-wave sleep phase. At the moment of awakening, the EEG allows you to register the presence of sharp waves. The prognosis in terms of the disappearance of epileptic seizures and EEG changes is relatively favorable (by puberty), but cognitive impairment remains in children [3–6].

Frontal nocturnal autosomal dominant epilepsy

Refers to isolated epileptic syndromes. Debuts before the age of 20 (usually around 11 years of age). Seizures occur when falling asleep and/or waking up (in the form of short - up to 1 minute, episodes of hyperkinesis, with or without loss of consciousness); epileptic seizures are preceded by an aura (a feeling of fear, trembling or somatosensory phenomena). Secondary generalized seizures occur in 50–60% of patients; In about a quarter of cases, attacks occur while awake.

Ictal EEG studies record sharp and slow waves or rhythmic low-voltage fast activity in the frontal leads. In the interictal period, EEG data may be normal or periodically show peaks in the frontal leads [3, 5, 9].

Conclusion

Among the epilepsies that occur in children of any age (0–18 years), it is necessary to list Kozhevnikovsky epilepsy (chronic progressive partial epilepsy, or epilepsia partialis continua), the clinical manifestations of which are well known to pediatric neurologists, as well as localization-related forms of epilepsy (frontal, temporal , parietal, occipital) [3]. The latter belong to symptomatic and probably symptomatic focal epilepsies, in which a wide range of symptoms is determined by the localization of the epileptogenic focus.

Read the continuation of the article in the next issue.

Literature

- Brown T. R., Holmes G. L. Epilepsy. Clinical guidelines. Per. from English M.: Publishing house BINOM. 2006. 288 p.

- Mukhin K. Yu., Petrukhin A. S. Idiopathic forms of epilepsy: systematics, diagnosis, therapy. M.: Art-Business Center, 2000. 319 p.

- Epilepsy in neuropediatrics (collective monograph) / Ed. Studenikina V. M. M.: Dynasty, 2011, 440 p.

- Child neurology (Menkes JH, Sarnat HB, Maria BL, eds.). 7 th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia-Baltimore. 2006. 1286 p.

- Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence (Roger J., Bureau M., Dravet Ch., Genton P. et al, eds.). 4 th ed. (with video). Montrouge (France). John Libbey Eurotext. 2005. 604 p.

- Encyclopedia of basic epilepsy research/Three-volume set (Schwartzkroin P., ed.). Vol. 1–3. Philadelphia. Elsevier/Academic Press. 2009. 2496 p.

- Aicardi J. Diseases of the nervous system in children. 3rd ed. London. Mac Keith Press/Distributed by Wiley-Blackwell. 2009. 966 p.

- Chapman K., Rho JM Pediatric epilepsy case studies. From infancy and childhood through infancy. CRC Press / Taylor&Francis Group. Boca Raton–London. 2009. 294 p.

- Epilepsy: A comprehensive textbook (Engel J., Pedley T.A., eds.). 2nd ed. Vol. 1–3. Lippincott Williams&Wilkins/A Wolters Kluwer Business. 2008. 2986 p.

V. M. Studenikin, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Economics

FSBI "NTsZD" RAMS, Moscow

Contact Information

Diagnostics

Neurologists diagnose and treat epilepsy. Some of them specifically expand their qualifications in this area, which allows them to act even more effectively.

Examination of a patient with suspected epilepsy includes the following methods:

- collection of complaints and medical history: the doctor asks the patient in detail about the symptoms that bother him, finds out the time and circumstances of their occurrence; a characteristic sign of epilepsy is the appearance of seizures against the background of sharp sounds, bright or flashing lights, etc.; special attention is paid to heredity, past injuries and diseases, the patient’s lifestyle and bad habits;

- neurological examination: the doctor evaluates muscle strength, skin sensitivity, severity and symmetrical reflexes;

- EEG (electroencephalography): a procedure for recording the electrical activity of the brain, allowing one to see the characteristic activity of an epileptogenic focus; if necessary, the doctor may try to provoke overexcitation using flashes of light or rhythmic sounds;

- MRI of the brain: makes it possible to identify pathological areas and formations: tumors, fissures, ischemic areas, consequences of a stroke, etc.;

- angiography of the vessels of the head: injection of a contrast agent into the blood followed by radiography; allows you to see areas of vasoconstriction and deterioration of blood flow;

- Ultrasound of the brain (Echo-encephalogram): used in children of the first year of life whose fontanel has not yet closed; visualizes tumors and other space-occupying formations, fluid accumulation, etc.;

- rheoencephalography: measurement of electrical resistance of head tissue, which can be used to diagnose blood flow disorders;

- general examinations: general blood and urine tests, blood biochemistry, tests for infections, ECG, etc. for a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s condition;

- consultations with specialized specialists: neurosurgeon, toxicologist, narcologist, psychiatrist, etc. (prescribed depending on the suspected cause of the attacks).

The list of studies may vary depending on the patient’s age, type of attack, presence of chronic pathologies and other factors.

Forecast

The prognosis depends on the type of disease. Idiopathic epilepsy is characterized by a benign course, maintaining the usual level of mental activity and cognitive abilities. Sometimes it disappears spontaneously after puberty. In the symptomatic form, the outcome is determined by the underlying disease.

In the absence of serious cerebral changes, adequate selection of drug therapy makes it possible to completely eliminate attacks or significantly reduce their frequency. Significant improvement after surgery is observed in 60-70% of patients, complete recovery in 30%.

At the Leto clinic you can get qualified help for partial forms of epilepsy. High-quality diagnostics and competent medicinal support will allow you to solve the problem and return to a full life. Sign up by phone..

Treatment of epilepsy

Treatment is a long and complex process. Even with the correct selection of medications and the complete absence of any manifestations for a long time, doctors only talk about stable remission, but not about complete elimination of the disease. The basis of therapy is medications:

- anticonvulsants (phenobarbital, clonazepam, lamotrigine, depakine and others): taken continuously to prevent seizures;

- tranquilizers (phenazepam, diazepam): eliminate anxiety and relax the body;

- neuroleptics (aminazine): reduce the excitability of the nervous system;

- nootropics (piracetam, mexidol, picamilon): improve metabolism in the brain, stimulate blood circulation, etc.;

- Diuretics (furosemide): used immediately after a seizure to relieve swelling in the brain.

If necessary, the doctor may prescribe other groups of drugs.

If medications are not effective enough, doctors may resort to surgery. The choice of a specific operation depends on the location of the pathological focus and the form of the disease:

- removal of a pathological formation (tumor, hematoma, abscess) that caused the attacks;

- lobectomy: excision of the area of the brain in which the epileptogenic focus occurs, usually the temporal lobe;

- multiple subpial transsection: used when the lesion is large or cannot be removed; the doctor makes small incisions in the brain tissue that stop the spread of excitation;

- callosotomy: dissection of the corpus callosum, which connects both hemispheres of the brain; used for extremely severe forms of the disease;

- hemispherotopia, hemispherectomy: removal of half of the cerebral cortex; the intervention is used extremely rarely and only in children under 13 years of age due to the significant potential for recovery;

- installation of a vagus nerve stimulator: the device constantly stimulates the vagus nerve, which has a calming effect on the nervous system and the entire body.

If indicated, osteopathy, acupuncture and herbal medicine can be used, but only as a supplement to the main treatment.

Make an appointment

Treatment

Involves constant use of anticonvulsants: phenobarbital, levitiracetam, valproic acid derivatives. Etiopathogenetic treatment is aimed at eliminating or mitigating the underlying pathology. Neurometabolites, vascular agents, vitamins, antibacterial and antiviral drugs are prescribed.

Ineffectiveness of conservative therapy and resistance to pharmacological support are indications for surgery. The purpose of the intervention is excision of the pathological focus (tumor, cystic formation) or direct resection of the epi-focus. The effectiveness of surgical methods increases with clearly localized areas of epileptogenic activity.

Complications

The most serious complication of epilepsy is status epilepticus. This condition is characterized by consecutive attacks of convulsions, between which the person does not come to his senses. This condition requires emergency medical attention due to the high risk of cerebral edema, respiratory arrest and palpitations.

A sudden onset of epilepsy can cause a fall and injury. In addition, frequent attacks and lack of quality treatment leads to a gradual deterioration of mental activity and personality degradation (epileptic encephalopathy). This is especially true for alcoholic epilepsy.

Briefly about classification

- Depending on the course and clinical manifestations, mild and severe forms are distinguished.

- Depending on the location of the affected area, there are generalized (specific and nonspecific syndromes) and localized (temporal, frontal, parietal, occipital).

A separate group includes such varieties of focal (local) form as Kozhevnikov syndrome (found mainly in children), specific syndromes (audiogenic, photogenic, startle epilepsy, etc.).

First aid for an attack

If a person has developed a classic attack of epilepsy with loss of consciousness, tonic and clonic convulsions, those around them should:

- If possible, prevent injury from falling;

- lay the patient on his side;

- Carefully hold your head during convulsions.

It is strictly forbidden to place spoons, pencils and other hard objects in the patient’s mouth to avoid biting the tongue!

If the convulsions do not stop, or the attacks follow one after another, you must urgently call an ambulance.

Symptoms of focal epilepsy

A common symptom for all types of pathology is a focal attack of epilepsy. Moreover, seizures recur with varying degrees of frequency. They can be simple and complex. In the first case, seizures occur at moments when the person is fully conscious, but motor, sensory and somatic autonomic symptoms are observed. Complex ones are characterized by clouding of consciousness for different periods of time, and serious manifestations of a mental nature, hallucinations, etc. occur.

By the way, complex seizures can begin as simple ones and are aggravated by loss of consciousness. The third type of pathology is non-malignant, that is, it does not lead to global impairments in speech, memory, and motor activity during the period of remission. If a child or teenager has symptomatic focal frontal lobe epilepsy, it may be accompanied by mental and psychological development. The clinical picture of the pathology directly depends on the location of the lesion and its size:

- Temple. The attack can last up to a minute, while an aura and automatism appear, in some cases there may be a loss of consciousness.

- Forehead. Characterized by serial attacks, absence of aura, turns of the head and eyes, and involuntary movements of the limbs. In this case, an attack can occur even in a dream.

- Back of the head. Prolonged seizures lasting up to 13 minutes, accompanied by visual hallucinations.

- Darkness. A rare pathology that occurs against the background of tumor processes. It is characterized by sensorimotor paroxysms, Todd's palsy, and impaired speech functions.

Most often there is one focus. It is the so-called epileptogenic zone. Under some conditions, activity is not limited to it, but spreads to the nearest sections, thereby causing characteristic disorders. In a number of situations, the development of secondary generalized paroxysms is allowed.

The hereditary disease is most often accompanied by generalized paroxysms and has a characteristic age of onset. In some cases, once a certain age is reached, the episodes stop. In such a situation, the use of antiepileptic medications is completed. On the other hand, forms have been identified in which drug therapy is lifelong.

Prevention and diet

Prevention of epilepsy is a healthy lifestyle. Doctors recommend:

- avoid stress and overwork;

- promptly treat any infections and inflammatory processes, including caries;

- minimize (or better yet, completely eliminate) intoxication, including alcohol and smoking;

- maintain body mass index within normal limits;

- regularly engage in sports at an amateur level, take more walks;

- get enough sleep and rest.

The diet for already diagnosed epilepsy, as well as an increased risk of its development, should comply with the principles of proper nutrition:

- sufficient quantity and correct balance of macro- and micronutrients (vitamins, minerals), as well as water;

- fractional meals in small portions;

- exclusion or sharp reduction of spices, coffee, black tea, carbonated drinks, etc.

Some forms of epilepsy can be corrected using a ketogenic diet, characterized by a minimum amount of carbohydrates, a medium amount of protein and a high amount of fat (up to 80% of all calories). The transition to this style of nutrition should only be carried out with the permission of a doctor and take place under his strict supervision.

Classification

The following types of partial (focal) epilepsy are distinguished:

Symptomatic. Formed as a result of other diseases. It is possible to determine the causes of development and detect corresponding changes based on neuroimaging data.- Cryptogenic. Presumably caused by another pathology, but the morphological basis is not revealed using imaging techniques.

- Idiopathic. There are no provoking diseases. The causes are disorders of brain maturation, hereditary membrane or channelopathies.

Advantages of the clinic

The Health Energy Clinic works to make quality medical care accessible to everyone. Our advantages are:

- doctors of various specialties who regularly improve their knowledge and skills;

- modern diagnostic equipment;

- the whole range of laboratory tests;

- comprehensive health screening programs;

- individual approach to the selection of therapy;

- own day hospital;

- affordable prices for all services.

Epilepsy is a disease that forces a person to live in constant fear of a new attack. Take control of your illness and sign up for Health Energy.

Signs of certain types of localized symptomatic epilepsy

Seizures in symptomatic temporal lobe epilepsy are characterized by the following symptoms:

- hallucinations;

- frozen look;

- feeling of fear and panic;

- speech and orientation disorders;

- thoughtless hand movements.

Seizures with symptomatic frontal lobe epilepsy typically have a sudden onset and abrupt end, and their duration rarely exceeds 30 seconds. Postictal confusion is usually absent.

Epileptic exacerbations can occur with:

- gestural automatisms, sometimes imitating sexual movements;

- visual hallucinations;

- inhibition or stopping of speech;

- involuntary urination.

Exacerbations occur frequently, including during sleep, and are characterized by a tendency to develop into generalized ones. Sometimes they are preceded by an aura - pallor, increased heart rate, difficulty breathing, difficult to control the urge to urinate.

Seizures in the parietal form occur with:

- pathological increase or, conversely, decrease in tactile sensitivity;

- sensation of “phantom” body parts;

- hypertrophied sexual desire;

- a tingling feeling (sometimes compared to an electric shock);

- visual hallucinations;

- dizziness;

- speech disorders.

Seizures with symptomatic occipital epilepsy are accompanied by:

- illusions;

- rotation of the head, eyes, twitching of the eyelids;

- dizziness;

- speech disorders;

- disorientation;

- severe headache (in intensity similar to a migraine).