There are generalized, focal (partial, local) and unclassified seizures (classification of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1981).

Generalized seizures include tonic-clonic, clonic, tonic, atonic, myoclonic seizures, as well as absence seizures, simple and complex (typical and atypical according to the EEG pattern). Clinically, generalized seizures are manifested by loss of consciousness (an obligate symptom), massive autonomic disturbances, and in some cases - bilateral convulsions, tonic, clonic or myoclonic. The EEG during a seizure reveals bilateral synchronous and symmetrical epileptic discharges.

Partial seizures are those whose clinical structure, as well as the EEG pattern, indicate pathological activation of an isolated group of neurons in one of the cerebral hemispheres. Partial seizures can develop into general - secondary generalized seizures. In the latter case, the partial discharge is the aura of the seizure. The clinical picture of partial seizures is characterized by symptoms of irritation (or loss) in one functional system: sensory, motor, autonomic, mental. There may be a disturbance or switching off of consciousness that occurs in various phases of the attack - complex partial seizures. Loss of consciousness is not an obligate manifestation of a partial seizure. Simple partial seizures are not accompanied by formal disturbances of consciousness.

Unclassifiable seizures cannot be described on the basis of the criteria adopted to distinguish the above-mentioned types of paroxysmal conditions. These are, for example, seizures of newborns with chewing movements, rhythmic movements of the eyeballs, hemiconvulsive seizures.

Seizures can be isolated, occur in series (temporarily increase their frequency, for example, up to six or eight times during the day), occur as status epilepticus (the debut of epilepsy, a special type of its course, a reaction to errors in anticonvulsant therapy, to high temperature and somatic diseases). Status epilepticus is a condition in which another seizure develops against the background of severe disorders associated with the previous one. The frequency of seizures during status is from 3 to 20 per hour (Karlov, 1990). In the status of generalized seizures, the patient does not regain consciousness.

Seizures are observed in epilepsy, in the clinical structure of current organic diseases of the brain - epileptic syndrome, and also as an expression of a nonspecific reaction of the body to extreme influences - epileptic reaction (Boldyrev, 1990). Epileptic syndrome (“symptomatic epilepsy” by some authors - H. G. Khodos, 1974) is observed in brain tumors, encephalitis, abscesses, aneurysms, hypertension and cerebral atherosclerosis, chronic mental diseases at remote stages of their dynamics, atrophic processes, parasitic diseases brain, metabolic disorders, chromosomal diseases. An epileptic reaction occurs in response to various factors: hypoglycemia, electrical trauma (a typical example is seizures during electroconvulsive therapy), intoxication (tetanus toxin), and medication, in particular Corazol. The cause of the epileptic reaction may be asphyxia. We have met teenagers who tried to induce euphoric states by mild asphyxia, and this was accompanied by seizures in some of them. One of the most common forms of epileptic reaction in children is febrile seizures (occurring against a background of high fever). Febrile seizures are more often observed in children (up to the age of five or six, there is a physiological increase in convulsive readiness). They occur during a high, especially “shooting” temperature reaction, are usually one-time, and do not have a focal component. In children suffering from epilepsy, seizures may become more frequent due to fever (this also happens in adult patients) or appear for the first time. Seizures of epilepsy are indicated by: their frequency, repetition with each rise in temperature, appearance at a low temperature (below 38°), the presence of a focal component, age over three or four years. Epileptic reactions occur especially easily with increased convulsive readiness. Their repetition can lead to the formation of epilepsy. Seizures of “reflex” epilepsy are also caused. The occurrence of a seizure is associated with sensory stimuli. The nature of the latter is reflected in the name of the attacks. Audiogenic seizures are triggered by sudden acoustic stimuli, while photogenic seizures are triggered by optical stimuli. Seizures can occur under the influence of tactile, proprioceptive and visceral stimuli (touching the body, sudden movement, pain). Rhythmically repeated stimuli can also lead to a seizure (flickering of oncoming train cars, electrical poles, zebra stripes on pedestrian sections of the road; images on a television screen - “television epilepsy”). Seizures are sometimes provoked by vegetative reactions (erection, defecation), complex but strictly defined actions (for example, a patient has seizures every time she goes to the sink, turns on the tap, and when the water starts to flow out, she loses consciousness). Sometimes seizures occur in connection with violent emotions - affective epilepsy. Probably similar to the latter are seizures associated with the perception of music - musicogenic epilepsy. Patients with reflex seizures can prevent, but sometimes, on the contrary, consciously cause them. Sometimes there are patients who experience an irresistible urge to cause seizures. This is due to affective disorders, auto-aggressive tendencies, or represents a special type of psychomotor seizure. Reflex seizures are more often observed in patients with epilepsy.

Here is a description of some epileptic seizures, initially generalized.

Tonic-clonic seizures. In the first, tonic phase, there is a sudden loss of consciousness, tonic tension of voluntary muscles, a fall, accompanied by a loud cry. There is cessation of breathing, increasing pallor of the skin and mucous membranes, followed by cyanosis. The pupils are dilated and do not react to light. Possible bites of the tongue, lips, cheeks. The tonic convulsions phase lasts 30-60 seconds. In the second phase, tonic convulsions are replaced by clonic ones. Breathing is restored, becomes noisy, intermittent. Foam comes from the mouth, often stained with blood. Involuntary loss of urine, feces, and semen is possible. Consciousness is deeply darkened. The second phase lasts up to two to three minutes. In the third, phase of epileptic coma, muscle hypotonia, pathological reflexes, mydriasis, and lack of pupillary response to light are detected. Coma gradually gives way to stupor, followed by deep, sometimes prolonged sleep. After an attack, post-ictal disorders are often detected: signs of stunned consciousness, dysphoria, fatigue, headache, lethargy, drowsiness. Sometimes there are episodes of twilight stupefaction. There are no memories of seizures. Before a seizure, its precursors may be observed (they should not be identified with an aura). Several hours and even days before a seizure, disturbances in sleep, autonomic regulation, general sensitivity, appetite, sexual need, and mood (subdepression, hypomania, dysphoria) occur. Depressive mood swings with anxiety and fears can cause painful anticipation and fear of a seizure. Patients are also afraid of attacks, after which subjectively painful post-ictal disorders remain - headaches, depression, fatigue, memory impairment, impoverished speech (oligophasia), post-ictal twilight episodes. The combination of affective and painful precursors with the absence of post-seizure disorders may explain why some patients look forward to seizures as relief, what exactly makes seizures so desirable. Before primary and secondary generalized seizures, there is an increase in absence seizures and focal paroxysms, respectively.

Individual phases of a tonic-clonic seizure may be omitted. Such seizures are called abortive. These include tonic, clonic seizures and non-convulsive seizures of epileptic coma (atonic or syncope seizures). The latter may be mistakenly regarded as fainting. Infantile, childish spasm.

West syndrome or West syndrome, infantile spasm, infantile myoclonic encephalopathy with hypsarrhythmia is manifested by propulsive seizures: convulsions of the eastern greeting, lightning-fast shudders and attacks in the form of nodding and pecking. The convulsions of the eastern greeting (tik salaam) occur in series, usually during the day. During a seizure, the body slowly leans forward, the head drops down, and the arms move to the sides and forward. Lightning-fast shudders - there is a sudden and sharp shuddering of the whole body, the head falls down, the arms are moved to the sides. Nods and pecks - the head quickly falls down and after a few fractions of a second returns to its previous position. The spasm is often accompanied by screaming, crying, play of vasomotors, dilation of the pupils, trembling of the eyelids, and grimaces. In children older than 10 months, retropulsive seizures may also occur (the head leans back, the torso extends). Seizures occur mainly in the morning. Infantile spasms occur against the background of severe encephalopathy and have an unfavorable prognosis. At the age of three years, infantile spasms are replaced by seizures of a different type, and an increasing delay in intellectual and overall personal development is revealed. The prognosis is especially depressing in cases of combination of propulsive seizures with others - clonic, tonic-clonic. On the EEG, against the background of depression of the main activity, high-amplitude asynchronous slow activity, sharp waves and multiple peaks are detected.

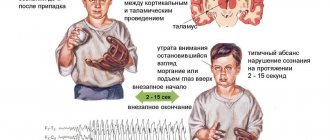

Absence

(minor seizure). Manifested by a short-term loss of consciousness. Clinically, simple and complex absence seizures are distinguished.

Simple absence is a short – up to 20 seconds – loss of consciousness. May be accompanied by paleness of the face and slight trembling of the eyelids. In isolated form, it occurs only in children. In childhood, absence seizures can occur in series - pycnolepsy or pycnoepilepsy, Friedman's syndrome. Seizure statuses are possible. It is observed between the ages of 4 and 10-11 years. During seizures of pycnolepsy, slight movements in the backward direction are sometimes performed - retropulsive seizures. The prognosis is favorable. There is no delay in mental development, although in some cases, upon reaching puberty, seizures do not disappear, but are transformed into others. On the EEG, against the background of normal bioelectrical activity, peak-wave complexes appear with a frequency of 3 discharges per second, as is typical for simple (typical) absence seizures.

Complex absence seizure is a short, in some types of attacks up to 1 minute, loss of consciousness, accompanied by the appearance of other disorders: hyperkinesis, changes in postural tone, autonomic disorders, and individual actions. In accordance with this, there are many types of complex absence seizures. Let's briefly describe some of them. Myoclonic absence - loss of consciousness is combined with shudders of the whole body in a rhythm of 3 discharges per second or myoclonic twitching of individual muscle groups. Consciousness may sometimes not be lost. Atonic absence (seizures of rapid fall) - loss of consciousness is accompanied by loss of muscle tone of the entire skeletal muscle or in individual muscle groups. The decline in postural tone can be gradual (slow subsidence of the body) or jerky at a rhythm of 3 discharges per 1 second or so. Such seizures are accompanied by a longer loss of consciousness—up to 1 minute—and are mistakenly regarded as short fainting spells. Akinetic absence seizure is a seizure with immobility, which can also result in falls. Hypertensive absence seizure (absence with tonic symptoms) - during an attack, an increase in muscle tone, retropulsive, rotational movements, flexion and extension of the limbs, etc. are observed. Absence with vegetative disorders: loss of urine, hypersalivation, paleness or redness of the face, etc. Absence with short-term elementary automatisms - individual simple movements are performed, actions started before the seizure are continued or completed.

The type of disturbance of consciousness during absence is, apparently, not established - there is no information in the literature on this matter, usually only the fact of switching off consciousness is indicated. Clinical data indicate, in our opinion, that the disturbance of consciousness during an absence seizure can be variable and ranges from mild stupor (nubilation) to stupor (for example, absence seizures with loss of urine). Clinically, a taxonomy of absence seizures depending on the depth of loss of consciousness would obviously be justified.

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (epilepsy with atypical absence seizures, myoclonic-astatic epilepsy). It manifests itself as atonic, tonic seizures and attacks of atypical absence seizures (triad of Lennox-Gastaut seizures). Observed between the ages of two and seven years, the disease is based on encephalopathy of unknown origin. Seizures (sudden falls, freezing, absences with automatisms, myoclonus) occur serially, lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 seconds. Delayed mental development, regressive symptoms (loss of previously acquired skills) are observed, and dementia is possible. The EEG picture is heterogeneous. After seven or eight years, the mentioned triad of seizures is replaced by generalized and complex partial seizures. Considered within the framework of secondary generalized epilepsy.

Propulsive epilepsy of Janz (myoclonic epilepsy of adolescents and young men). It is characterized by massive bilateral myoclonus (mainly in the muscles of the arms and shoulder girdle), primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures (sometimes secondary generalized, following myoclonus) and absence seizures, including complex ones. It is differentiated from Unferricht-Lundborg myoclonus epilepsy. Progressive familial myoclonus-epilepsy of Unferricht-Lundborg is characterized by a consistent complication of the clinical structure: nocturnal tonic-clonic seizures are joined by myoclonus after a number of years, then personality changes (intrusiveness, explosiveness, demandingness), and then muscle rigidity and dementia occur. Myoclonus is asymmetrical, irregular, disappears during sleep, intensifies with excitement and sensory stimulation, and its intensity varies from one day to the next. On the EEG, against the background of the absence of alpha rhythm, short paroxysms of sharp, slow waves, peak-wave complexes, symmetrical in both hemispheres, are recorded. Janz epilepsy is usually observed between the ages of 12 and 18 years. It's going well. There is no mental retardation, but a delay in personal development is possible - infantilism. The EEG shows spike-wave complexes of 3 per 1 second (typical absences), 1-2 per 1 second (atypical absences), polyspikes with a frequency of 4-6 per 1 second and subsequent slow waves are characteristic. With age, myoclonic paroxysms disappear.

Rolandic epilepsy. It manifests itself as pharyngeal seizures (swallowing, chewing, licking, hypersalivation in combination with paresthesia in the throat and tongue, a feeling of suffocation), as well as unilateral facial seizures. It is observed between the ages of 4 and 10 years. Seizures are rare, secondary generalization is possible, and often occur during sleep. The prognosis is favorable, the development of children is not impaired. On the EEG, against the background of preserved basic rhythms, peaks and high-amplitude sharp waves of central temporal localization are noted. Refers to focal epilepsy.

Landau-Kleffner syndrome. The typical onset of the disorder is between the ages of three and seven years. After a period of normal speech development, there is a gradual or very rapid loss of both receptive and expressive language skills. Some children become mute, others are limited to slang-like sounds, fluency of speech, articulation, and prosodic aspects of speech are impaired. At the same time, paroxysmal deviations in the EEG (in the temporal and other parts) and epileptic seizures are detected. The onset of seizures may precede speech disorders.

Rett syndrome. Begins between 7 and 24 months of age and has been described in girls. A period of normal early development is followed by partial or complete loss of manual skills, slowing of head growth, loss of intentional hand movements, handwriting stereotypies, and shortness of breath. Social and play development is delayed in the first two or three years, although social interests are partially preserved. In middle childhood, trunk ataxia, apraxia, kypho- or scoliosis, and sometimes choreiform hyperkinesis occur. Epileptic seizures are often observed in early and middle childhood, resulting in severe mental disability.

Riley-Day disease. Convulsive syndrome is combined with dry mucous membranes, paroxysms of hyperthermia, and the absence of fungiform papillae on the tongue. Occurs in patients of Jewish nationality. Epileptic foci of primary generalized seizures are localized in the brain stem.

Partial or focal seizures.

They manifest themselves as paroxysms of isolated disturbances of any functions - motor, sensory, autonomic, mental. In this case, stunned consciousness or confusion may occur, that is, complex focal seizures occur. The following types of seizures are classified as partial. Bravais-Jackson somatomotor seizures - paroxysms of clonic convulsions are observed in the muscles of the limbs and face on one half of the body. Clonic jerks most often occur in the orofacial muscles. Convulsions spread in different sequences. With their transition to the face, generalization of the attack into a general seizure is possible. Adversive seizures are a tonic convulsion with a rotation of the eyes, head and torso in the direction opposite to the localization of the epileptic focus. As a rule, it is accompanied by secondary generalization of the attack. Oculoclonic seizures are clonic abduction of the eyeballs (epileptic nystagmus). Oculotonic seizures are tonic abduction of the eyeballs (epileptic gaze convulsions). Version seizures are rotation of the body around its own axis. Somatosensory seizures are paroxysms of paresthesia on half the face and limbs opposite to the lateralization of the epileptic focus. More often they generalize into a general seizure. Speech or phonatory seizures are paroxysms of speech disorders (pronunciation of individual words, phrases, sometimes meaningful, their iterative repetition, sudden loss of speech) and phonation. Sensory seizures are paroxysms of elementary or simple hallucinations (auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, gustatory, vestibular) and senestopathic sensations. For the most part, generalization occurs into a general seizure. Somatosensory Jacksonian seizures are attacks of paresthesia on half of the body on the side opposite to the localization of the epileptic focus (postcentral gyrus). Autonomic seizures of isolated autonomic disorders (severe pain in the epigastrium, abdomen, heart area - “abdominal epilepsy”; “epileptic angina pectoris”; breathing disorders - “epileptic asthma”; dysuric disorders, vegetative-vascular disorders), observed when the epileptic focus is localized in cortical parts of the temporal lobe of the brain (orbitoinsulotemporal region). Autonomic seizures can only manifest as dilated pupils - “pupillary epilepsy.” Abdominal and epigastric seizures are more common in children aged three to seven years. They are accompanied by a deafening of consciousness, which makes memories of them unclear. General vegetative paroxysms, combined with stunned consciousness and tonic convulsions - diencephalic epilepsy - are distinguished from cortico-visceral vegetative seizures. It is not mentioned in modern classifications.

In addition to the above, focal seizures with various psychopathological phenomena (“mental equivalents”, “paroxysmal epileptic psychoses”, “mental epileptic seizures”) are observed. The epileptic focus is most often found in the temporal lobes of the brain - “temporal lobe epilepsy.” Epilepsy, manifested by isolated mental equivalents, is also referred to as “larved” or “masked” epilepsy. The question of the differences that exist between mental seizures and acute psychoses in epilepsy is not very clear - where is the border separating them from each other, or at least what is the duration of the seizure itself. If we accept that the cycle of a generalized seizure (precursors - attack - post-seizure disorders) lasts up to 6-7 days, then we must agree that the duration of mental paroxysm can fluctuate within the same limits. We use the term “mental equivalents” not in its original meaning, but in a conventional sense and rather out of habit.

Various clinical variants of mental equivalents are observed: attacks of stupefaction, psychomotor seizures, paroxysms with affective, delusional, hallucinatory and ideational disorders, as well as special states of consciousness.

Attacks of clouding of consciousness are manifested by twilight, oneiric and delirious paroxysms. Twilight states (see “Disturbances of consciousness”). Attacks of epileptic delirium develop and end suddenly, accompanied by more extensive amnesia than usual. Seizures of epileptic oneioid also occur suddenly, without the change in individual stages of development established for schizophrenia. An ecstatic state, hallucinations of mystical content, stupor, detachment from reality or its illusory perception, in tune with the mood, are observed.

Psychomotor seizures are characterized by aimlessly performed actions, the nature of which is determined by the depth of the disturbance of consciousness and the immediate environment in which the patient is at this time. Depending on the degree of complexity and type of actions performed, the following types of psychomotor seizures are distinguished.

Fugues are attacks of rapid flight, rotation around the axis of the body or running in a circle (so-called manege actions), lasting for several seconds.

Outpatient automatisms - attacks with automatisms of walking. Patients wander around the city, go to unfamiliar places, and when they wake up, they do not remember where they were or how they got here.

Trances are multi-day attacks during which patients travel long distances using modern types of transportation. Patients attract the attention of others, perhaps only by increased drowsiness, taciturnity, absent-mindedness, as if immersed in some kind of reflection, but in general, external behavior remains orderly. It seems that in trances ancient, in Jung's terminology, archetypal nomadic complexes are released.

Gesture automatisms are short-term seizures during which patients perform isolated and incorrect actions: rubbing their hands, moving furniture from place to place, taking contents out of pockets or putting everything that comes to hand there, undressing, pouring water on themselves, urinating in plain sight. everyone has. Thus, one of the patients, a pathologist by profession, broke instruments and cut telephone wires during seizures. During the autopsy of the corpse, he separated pieces of tissue and ate them. He opened the car doors and tried to get out at full speed.

Speech automatisms - phrases, monologues, curses are pronounced, poetry is recited. Seizures with speech automatisms are similar to partial speech seizures; it is hardly possible to differentiate them clinically, as are some other psychomotor and motor seizures.

Automatisms of expressive actions - during a seizure there is senseless, wild laughter (“fits of crazy laughter” by Jackson), sobs, screams, singing, dancing, grimacing, poses expressing joy, fear.

Complex automatisms are seizures during which complex, seemingly meaningful and appropriate actions are performed. There are reports according to which patients during such attacks are able to perform complex work and even creative work: create a work of art, pass an important exam, solve a mathematical problem, etc.

Along with the above, paroxysms of affective disorders may occur: dysphoria, manic and depressive states. Dysphoria is attacks of melancholy and angry mood against the background of clear consciousness. Mania and depression, also occurring paroxysmally, resemble circular affective shifts. For epileptic mania, ecstatically enthusiastic elation is more characteristic, for depression - a gloomy shade of mood and the possibility of the appearance of impulsive desires.

Special states of consciousness (similar paroxysms are described under other names: psychosensory seizures, dream-like states, temporal pseudoabsences) differ from absence seizures in their relatively slow onset and termination, longer duration (minutes, tens of minutes), and the presence of various psychopathological symptoms. The phenomena of autometamorphopsia (macrosomia, microsomia, etc.), metamorphopsia (macropsia, micropsia, porropsia, etc.), disturbances in the perception of time, derealization, the phenomena of “already seen, heard, experienced” and “never seen, heard, experienced” are observed. ", disturbances in the perception of color quality, isolated hallucinations, fragments of fantastic dream-like delirium, fear, melancholy, confusion, massive vegetative disorders. During the attack and after it, an understanding of the painfulness of the condition remains. Memories of subjective experiences of this period are quite complete, but memories of external events are fragmentary or absent. Amnesia is possible for part (at the beginning, in the middle, at the end) of the attack, which is associated with stunned consciousness. In this case, the seizure, according to currently accepted terminology, is designated as a complex partial seizure. Attention should be paid to the fact that in their reports patients sometimes only mention “outages,” which can create a false impression. absence seizure Complex partial seizures differ from absence seizures in their structural complexity, duration (several minutes, up to 10 or more), and the absence of typical discharges on the EEG - three peak-wave complexes per second.

Ideation seizures are attacks of violent flow or stopping of thoughts and memories. Amnestic seizures reflect limbic disorders and are manifested by short episodes of loss of memory for past events. Ecmnestic seizures are hallucinatory, violent memories of the real past.

Temporal seizures can occur in isolation, but their secondary generalization into a major attack is possible, after which the psychosis is self-limited. With high convulsive readiness, very rapid generalization occurs, the psychotic episode does not last long and, as already mentioned, is the aura of a seizure.

The above list probably does not exhaust the variety of mental attacks. In addition, it shows that there is no satisfactory classification. The taxonomy of mental seizures, according to the literature, is based on psychological criteria and is mostly carried out from the position of structuralist psychology. This implies both the terminology (“cognitive”, “emotional” seizures, seizures with disturbances of perception, etc.), as well as the inevitable difficulties with this approach in distinguishing between different paroxysms and the static nature of assessments. Modern psychopathology in the taxonomy of mental disorders uses a syndromic, that is, clinical-pathogenetic approach. It does not appear to have been applied to mental attacks. The resulting idea is that mental seizures can be classified according to the severity scale of productive mental disorders. Thus, it becomes possible to arrange seizures depending on the depth of damage to mental activity, to establish hierarchical relationships between them; perhaps identify yet unaccounted for types of paroxysms, or even suggest their existence; determine the severity and direction of the course of temporal lobe epilepsy, the effectiveness of drug therapy, based not only on quantitative criteria (frequency), but also on an analysis of the clinical structure of paroxysms; in cases of gradual development of an attack, evaluate the stages and “march” of pathological conditions that change during the attack.

Partial seizures with mental pathology, if you follow the syndromic principle, can be located in the following sequence (presentation is in order of increasing severity):

1. Seizures with symptoms of a psychosomatic level: disturbances of sleep, desires, general sensitivity, activity, autonomic regulation. These are seizures with episodes of drowsiness, reminiscent of narcoleptic paroxysms, attacks of epileptic dreams, paroxysms of sleepwalking and sleep-talking. Further, these are cortical vegetative paroxysms, seizures with various disorders of general sensitivity, in particular, senestopathies, drives (bulimia, increased libido).

2. Seizures with affective pathology - dysphoria, manioform and depressive paroxysms.

3. Seizures with symptoms of a neurotic level: depersonalization and derealization, mental anesthesia, obsessive, hysterical phenomena. Hysterical seizures can probably be actually epileptic, and in this case it is not advisable to distinguish them from seizures of epilepsy. Another thing is their difference from convulsive seizures. Hysteriform paroxysms in patients with epilepsy differ from actual hysterical (neurotic) seizures in greater severity: the absence of photoreaction of the pupils - Redlich's symptom, less contact between patients, and decreased responsiveness to external influences. It is more difficult to modify and abort the seizure. There may be biting of the cheeks, loss of urine, minor bruises, seizures are more stereotypical, last longer and leave behind fewer memories. Hysteriform seizures can also be combined with tonic-clonic ones or develop into the latter. Classic differential diagnostic tables of signs distinguishing hysterical and epileptic seizures seem to be built on a comparison of different classes of phenomena, and therefore have rather academic significance. As for hysteriform seizures in patients with epilepsy, they have been known for a long time and are described under different names (subcortical, intermediate, hysteroepileptic, severe hysterical seizures). The main difficulty in differential diagnosis is that they are phenomenologically similar to functional seizures.

4. Seizures with delusional-hallucinatory symptoms - delusional, hallucinatory, paranoid, hallucinatory-paranoid, paraphrenic. Perhaps there are epileptic paroxysms with catatonic symptoms.

5. Seizures with disturbances (confusion) of consciousness: oneiroid, delirium, twilight stupefaction, motor, expressive automatisms (fugues, trances, ambulatory automatisms).

Along with seizures, during which productive psychopathological symptoms occur, paroxysms with negative symptoms are observed. These are, for example, seizures with stunning seizures (absences, complex partial seizures), stupor and coma (non-convulsive seizures), amnestic seizures, and Sperrung-type seizures. This probably does not exhaust all the variants of “negative” epileptic paroxysms.

Institute of Child Neurology and Epilepsy

Many of us have seen how people have epileptic seizures in public places, which most often make a frightening impression on others.

The reactions of most surrounding people are divided into two types: some simply pass by, while others get scared, begin to panic and often suggest methods of influence that can be dangerous. There is another persistent prejudice that during an attack there is no need to provide assistance. Indeed, most epileptic seizures stop spontaneously after a few minutes. However, during an attack, the patient still needs the help of others.

The degree of trauma to the patient and the timeliness of calling qualified medical assistance if necessary depend on the calm and thoughtful actions of those nearby. An epileptic seizure, even if it has not occurred for the first time, is a fairly strong stressful situation both for the patient himself and for those around him (family, friends, colleagues, etc.)

We present to your attention several reminders that we have developed directly for patients suffering from epilepsy, as well as for people who are ready to help in such situations. We hope that this information will help the patient partially protect himself from injury, and help those around him not to become confused in the event of an attack and to provide timely and correct assistance.

Memo No. 1. Patient

1. Always carry an identification bracelet with you (in emergency situations, information about the form of epilepsy, types of seizures, medications used, as well as contact numbers can be useful to people helping you).

2. Make sure that your family members, close people, perhaps one of your work colleagues to whom you trust information about your illness, are aware of what actions to take in the event of an attack.

3. If you have frequent attacks, avoid potential dangers in your home (moving mechanisms, sources of fire, hot objects, bathtubs and swimming pools filled with water, etc.)

4. Also avoid sports that are potentially dangerous for you - swimming, gymnastics, rock climbing, motorcycling, horse riding, etc. Activities such as cycling, hockey, kayaking, canoeing, etc. may sometimes be acceptable with full protective gear. When playing any sport, it is better to always have a person nearby who is able to provide you with the right help in case of an attack. If you decide to engage in this or that sport, it is recommended to first notify your doctor and listen to his opinion on this matter.

5. Keeping a diary of attacks will help you more accurately navigate their frequency and time of occurrence, as well as identify provoking factors. This is very important for the attending physician.

Memo No. 2. Persons providing assistance for a generalized seizure.

1. Remove all objects located in the immediate vicinity of the patient that could harm him during an epileptic attack (sharp, hot objects, glass, etc.).

2. Place a soft, flat object (pillow, folded sweater, bag, package) under your head.

3. If possible, ease the pressure on the neck of clothing that may impede breathing (unbutton your collar or untie your tie), you can also loosen your waist belt.

4. Until the convulsions stop, transfer the patient to a position lying on his side, carefully hold him until the end of the attack. It is not recommended to forcefully hold patients during an epileptic attack to avoid causing accidental injuries.

5. Record the time of onset of the epileptic seizure to determine its duration.

6. Do not put any objects in the mouth (tablets), and do not attempt to open the patient’s jaws (with a spatula, spoon, your hand, etc.) - this can knock out teeth or injure the jaw. These actions can lead to the entry of solid objects (tablets, teeth) or blood into the respiratory tract and even to the death of the patient.

7. Do not feed, do not give water or tablets until the patient fully regains consciousness.

8. There is no need to perform artificial ventilation and chest compressions during an attack. This is necessary in cases where the patient did not breathe on his own after an attack.

9. If the attack happened to a stranger, look in his things for documents confirming a possible illness or an identification bracelet.

10. Always remain with the patient until he is fully conscious. Make sure there are no breathing problems and consciousness is restored. Remember that vomiting is possible after an attack; give the patient a comfortable position (on his side) that will prevent vomit from entering the respiratory tract.

11. Be patient with the patient, inform him that he was having an attack, reassure him if necessary. Ask a few simple questions, the answers to which will help you assess your level of consciousness (What is your name? Where are we located? What date and day is it today?).

12. Urgent medical care is not mandatory if the patient is diagnosed with epilepsy and at the same time:

- the patient reported that similar types of attacks had been observed before, his health was close to normal, he was calm and answered questions adequately

- the epileptic seizure lasted no longer than 5 minutes

- the patient was not injured during the attack

If there is no need to provide qualified medical care, offer your help to the person after an attack - call relatives, friends, or take them home.

If necessary, call emergency medical assistance by calling 03 or 112.

It is important to know the situations in which it is necessary to resort to qualified medical assistance.

These may be the following cases:

- an epileptic attack occurred for the first time in life;

- the duration of the attack is more than 5 minutes;

- the patient has respiratory dysfunction;

- regaining consciousness after an attack is slow, confusion is noted;

- the next attack occurred immediately after the previous one (serial attacks);

- an epileptic attack occurred in water;

- the attack occurred in a pregnant woman;

- there are doubts that it was precisely an epileptic attack;

- there is evidence of diabetes mellitus, neuroinfections, poisoning, high body temperature, head injuries;

- The patient was injured during an epileptic attack.

Memo No. 3. Absences and focal (partial) seizures.

| Type of seizures | Recommended Actions |

| Absences (episodes of freezing with complete loss of consciousness for 3-30 seconds) | 1. Carefully observe the child and his subsequent actions. 2. Say a few numbers and ask your child to repeat. If there is an answer, this will help estimate the duration of the episode. 3. Calm your child if he is scared or confused after a seizure. 4. Record the duration of the episode and the frequency of attacks. 5. If possible, record it on video, for example, using a mobile phone. |

| Partial (focal) attack | 1. Give the child a comfortable position, gently holding him. 2. Carefully observe the child and his subsequent actions. 3. Ask simple questions - this will help assess the child’s level of consciousness. 4. Reassure your child if they are scared or confused after a seizure. 5. Record the duration of the episode and the frequency of attacks. 6. If possible, record it on video. Actions during the transition of a partial attack to a generalized one - see memo No. 2. |