Epilepsy is a chronic disease of the central nervous system characterized by the occurrence of two or more epileptic seizures that begin suddenly and involuntarily, usually last a short period of time, and can sometimes be caused by bright and flickering flashes of light. Epilepsy ranks third in the structure of neurological diseases and is a pathology that can occur in both children and adults. In 1981, the International League Against Epilepsy created a unified classification of epileptic seizures, according to which there are partial (focal, local) and generalized seizures (GS). In this article we will look at what generalized epilepsy (GE) is.

GE is a type of epilepsy accompanied by signs of primary diffuse involvement of cerebral tissues with a pronounced increase in mental and motor activity. The following types of generalized seizures are distinguished:

- absence (typical petit mal and atypical);

- myoclonic;

- clonic;

- tonic;

- tonic-clonic (grand mal);

- atonic.

The essence of the classification is that it takes into account the subtle neural organization of the brain with specific functions that are localized in certain areas. GPs are characterized by the absence of a specific place of origin of the pathological focus of excitation; it can be generated in both hemispheres.

In addition to this classification, generalized seizures are divided into:

- idiopathic generalized (related to age-related characteristics);

- generalized cryptogenic and/or symptomatic;

- generalized symptomatic of nonspecific etiology (related to age-related characteristics);

- specific epileptic syndromes.

There are also partial (having a specific location of origin of the source of excitation in the brain, for example, temporal lobe epilepsy or parietal) seizures that can transform into secondary generalized ones (excitation passes to both hemispheres).

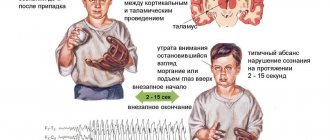

GP can be convulsive and non-convulsive (absence and atonic). Absence seizures are most common in children 4-8 years old. During an attack, which lasts a maximum of 10-20 seconds, they have no consciousness, any ongoing activity is interrupted, the child becomes like a statue with a blank look, he does not respond to anyone addressing him. Simple absence seizures can be repeated a large number of times a day, but the patient will not remember them - they are not felt by him at all. There are also complex absence seizures - they are simple absence seizures with the addition of bilateral motor phenomena (twitching, tension of facial muscles, nodding the head, moving the eyes to the side, etc.). An atonic attack occurs suddenly with loss of postural muscle tone, as a result of which the patient falls and there are no convulsions.

Convulsive seizures, in turn, are divided into tonic, clonic, myoclonic and tonic-clonic.

Tonic attacks are characterized by spasms of the muscles of the face and torso, accompanied by flexion of the arms and extension of the legs, impaired consciousness, and falling. The attack begins suddenly and also ends suddenly, after which the patient remains in a confused state for a short time.

Clonic seizures are repeated bilateral jerking of the limbs, usually irregular. The seizure also suddenly begins and ends; towards the end, the frequency of contractions decreases.

Myoclonic seizures are sudden, lightning-fast involuntary muscle contractions (blinking, head nodding) without loss of consciousness. They can be generalized (muscles of the trunk and limbs are involved) or limited (in the face or in one limb).

Tonic-clonic seizures are the condition most often shown in films or TV series and are the most frightening to witness. A generalized tonic-clonic seizure has characteristic features not found in other types, which makes diagnosis easier. Its occurrence is unexpected, the patient loses consciousness, emits an “epileptic cry” (due to contraction of the muscles of the diaphragm and pectoral muscles). After this, a tonic phase begins with tension of the whole body, followed by a clonic phase with generalized twitching and the release of reddish foam from the mouth as a result of biting the cheek or tongue. This is accompanied by facial cyanosis, severe tachycardia and increased blood pressure. Between the listed phases there is a relaxation phase, during which involuntary bowel movements or urination often occur. The attack lasts up to 2 minutes, but the patient can remain unconscious for up to 15 minutes. For a long time after the seizure, he will suffer from headaches, nausea and confusion.

Causes of GE

Epilepsy is a polyetiological disease that can be caused by any disease or injury to the central nervous system. Every structural damage to the brain causes an imbalance of inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters. Because of this, the neuron membrane becomes more permeable to Na+ and Ca2+ ions, and the number of channels for K+ and Cl-, on the contrary, decreases. As a result, neurons become hypersensitive to the discharges of other neurons, which leads to the formation of an epileptic focus.

Structural brain disorders can occur due to the following reasons:

- perinatal - viral infections of the mother during pregnancy (rubella, herpes), the mother's use of toxic drugs and medications prohibited for pregnant women, birth injuries;

- postnatal - concussions and other injuries, central nervous system infections (meningitis or encephalitis), tumors and hemorrhages.

If one of the parents has epilepsy, then the risk of it occurring in the child is no more than 10%.

Based on their appearance, epilepsy is divided into idiopathic, symptomatic and cryptogenic. Idiopathic - epilepsy with a known or possible genetic predisposition. Such patients do not have a history of head injuries, no brain damage is detected during examination, and there are no mental disorders before the attack occurs. Symptomatic - seizures occur as a result of exogenous factors leading to brain damage (trauma, infection, hemorrhage, ischemia, etc.) with manifestation. Cryptogenic is characterized by the absence of any cause; the epileptic syndrome occurs spontaneously.

Expert opinion

Author: Olga Vladimirovna Boyko

Neurologist, Doctor of Medical Sciences

According to the latest WHO data, epilepsy affects 4-10 people per 1000 population. Currently, doctors are registering an increase in incidence. This is due to various provoking factors. It has been proven that epileptic seizures occur more often in residents of countries with a low or average level of development, however, in Russia the disease accounts for 2.5% of cases of neurological pathology. Epilepsy ranks first in the structure of disability: 30% of patients become disabled in groups 1 or 2.

Epilepsy can manifest itself against the background of other diseases - this type of pathology is called symptomatic. Doctors at the Yusupov Hospital perform thorough diagnostics to determine the causes of seizures. This is necessary to prescribe the correct therapy. The examination is carried out using European equipment. The diagnosis is made based on MRI, CT, and EEG data. In a modern laboratory, blood diagnostics are carried out. Symptomatic epilepsy requires an individual approach to treatment. Neurologists at the Yusupov Hospital are developing a personal treatment plan, including new drugs with proven effectiveness.

Epidemiology of childhood epilepsy abroad

Febrile seizures occur in 2-4% of young children in the United States, South America and Western Europe. Their frequency is higher in Asian countries. A number of large prospective studies have determined that in approximately 20% of cases, the first febrile seizures were complex (lasting more than 15 minutes, being focal, or occurring at least twice within 24 hours). Most often they occur during the second year of life. FS are somewhat more common in boys [28,44,45,47].

Long-term studies show that the incidence of a particular type of epileptic seizure also depends on age. Thus, myoclonic seizures are more often observed in the first year of life - 10-15/100,000. The incidence of generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the first year of life is 15 per 100,000, in 10-65 years - 10 per 100,000, after 65 years - 20 per 100,000 [29,32]. Partial (focal) seizures are observed with a frequency of 20 per 100,000 from 1 to 65 years, at older ages their frequency increases to 40 per 100,000. Absence seizures have a clear dependence on age and occur mainly before 10 years of age with a frequency of 11 per 100,000 [ 36].

According to the US Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, in the state of Oklahoma, the average incidence of epilepsy is 5-7 cases per 10,000 children per year from birth to 15 years of age [25].

According to studies of the epidemiology of infantile spasms (West syndrome) in children in Atlanta (USA), the incidence was 2.9 per 10,000 live births; in 50% of children the etiology could not be established (cryptogenic forms). Among 10-year-old children, the prevalence of epilepsy was slightly lower - 2.0 per 10,000, of which 83% of children had neurological pathology and had moderate mental retardation (IQ < 70), and 56% had profound mental retardation (IQ < 20) . Infantile spasms were quite rarely recorded in the general population, and were more common in children with neurological pathology [26].

Studies conducted in France (2004-2005) showed that the prevalence of childhood epilepsy was 115.4 per 100,000 [95% CI 106.7-124.0], the primary incidence was 99.5 per 100,000 in the age group 0- 14 years old [39].

Studies conducted in Italy (1968-1973) among school-age children revealed a high incidence of epilepsy - 4.91%, of which generalized forms - 30.8%, rolandic epilepsy - 23.9%, other types of focal epilepsies - 42.1%, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome - 3.2%. Over a 4-year observation period, 55% of sick children achieved complete recovery, 24% showed positive dynamics (a reduction in the frequency of attacks by more than 50%) [24].

In Finland, the prevalence of childhood epilepsy was 3.94 per 1000 children. According to researchers, the generalized nature of seizures was typical for children aged 0-6 years, and the focal nature - for children aged 6-15 years [33].

In Spain, 62.1 cases of various forms of childhood epilepsy are registered annually per 100,000 children. The highest rate of disease registration was observed in the first year of life (103.9 per 100,000). In early childhood, symptomatic forms of epilepsy accounted for 21.3%, and cryptogenic forms - 25.5%. In primary and senior school age groups, idiopathic epilepsy accounted for 25.6%, and cryptogenic epilepsy - 20.5%. In adolescence, cryptogenic epilepsies accounted for 21.1%, and idiopathic epilepsies - 18.4% [29].

According to epidemiological studies in Pamplona (Spain) (2002 - 2005), the prevalence of epilepsy among the child population was 62.6 per 100,000, with a peak (95.3 per 100,000) during the first year of life. Idiopathic forms accounted for 45.5%, cryptogenic - 29.0%, and symptomatic - 25.5%. Focal seizures were noted in 52.9% of patients, and generalized seizures in 43.5%. Among infants, West syndrome accounted for 45.5%, its symptomatic forms 13.6%. In early childhood, symptomatic (22.7%) and cryptogenic forms (21.2%) of epilepsy and Duse syndrome (13.6%) predominated. Among school-age children, idiopathic benign (27.8%) and cryptogenic forms (18.5%) of epilepsy were more common. In adolescence - cryptogenic forms (26.6%) and idiopathic (23.4%) [30].

Similar studies were conducted in the province of Navarra (Spain): the primary incidence of epilepsy among the child population was 62.6 cases per 100,000 [95% CI 62.3-62.9]. The incidence among children of the first year of life (95.3 per 100,000) and gradually decreased towards adolescence (48.7 per 100,000). Focal epilepsy was registered in 55% of cases, generalized forms - in 42.9%. In infants, the most common forms were West syndrome (45.5%), symptomatic (27.5%) and cryptogenic (13.6%) epilepsies. In early childhood, symptomatic (22.7%) and cryptogenic (21.2%) epilepsies predominated, and Duse syndrome accounted for 13.6%. In school-age children, idiopathic (27.8%) and cryptogenic (18.5%) epilepsies predominated. In adolescents, cryptogenic (27.6%) and idiopathic (18.4%) epilepsies were more often recorded [31].

According to the morbidity registry in Stockholm (Sweden), the primary incidence of epilepsy was 33.9 per 100,000, and in the first year of life this figure was 77.1 per 100,000 [18].

The prevalence of childhood epilepsy in Norway in 1995 was 5.1 per 1000 children, with symptomatic and cryptogenic forms predominating in boys. Symptomatic epilepsy accounted for 46%, of which 81% of cases were drug-resistant [48].

In the coastal province of Cameroon, the prevalence of epilepsy is 105 per 1000 children: generalized forms - 35.3%, focal forms - 64.7% [41].

Epidemiological studies conducted in Okayama Prefecture (Japan) in 1999 showed that among children under 13 years of age, 2,220 had epilepsy (out of a total pediatric population of 250,997 children). The most common types of seizures were generalized tonic-clonic (40.7%) and infantile spasms (21.0%) [19]. The incidence of infantile spasms was 0.25-0.42 per 1000 live births per year. Among children under 10 years of age, the incidence ranged from 0.14 to 0.19 per 1000. The peak incidence of infantile spasms was between 4 and 6 months of age, with a higher incidence among boys [27].

In Singapore, the incidence of childhood epilepsy was 3.8 per 1000 children, and mortality reached 0.5 per 100,000 children [42].

The epidemiology of childhood epilepsy in the population of Chinese children (Hong Kong, 2001) is similar: the prevalence was 4.5 per 1000 children under the age of 19 years. Idiopathic epilepsy was observed in 42% of children, cryptogenic - 16.8%, symptomatic - 40.8%. The frequency of focal seizures was 48.5%, and generalized seizures - 46.9%. Moreover, generalized seizures were more common in children of the younger age group (under 5 years) [38].

Studies conducted in South India (1989 - 1994) identified 2531 cases of epilepsy among children, of which cryptogenic forms accounted for 48%, symptomatic - 62.9%, and idiopathic - 0.7% [40].

The prevalence of epilepsy in Pakistan is 9.99 per 1000 people, the highest rate among the population under 30 years of age, more often in rural areas. Idiopathic epilepsy predominated in children (76% of cases) [37].

Interesting epidemiological studies of childhood epilepsy in Arab countries, where 724,500 people suffer from epilepsy. The prevalence of epilepsy is 2 times higher in children and adolescents. In Qatar, the prevalence was compared with the average of 174 cases per 100,000 children, in Sudan - 0.9 per 1000 and 6.5 per 1000 in Saudi Arabia. Idiopathic forms of epilepsy accounted for 73.5-83.6% of cases. The main causes of symptomatic childhood epilepsy are cerebral palsy (CP) and mental retardation. In Sudan, one of the main causes of symptomatic epilepsy was infectious diseases of the central nervous system [23].

Studies conducted in the Republic of Tanzania (East Coast of Africa) revealed a prevalence of childhood epilepsy of 11.2 per 1000 [95% CI 8.3-13.9 per 1000], newly diagnosed epilepsy was 8.7 per 1000 [95% CI 6. 7-11 per 1000] [27].

The prevalence of epilepsy in Tunisia was 4.04 per 1000, with the highest rates in children and adolescents. In 93% of cases, generalized seizures were recorded, and the main etiological factor was cerebral palsy and mental retardation [21].

In a comparative study of the epidemiology of epilepsy in Pakistan and Turkey, researchers showed that the prevalence of epilepsy in Pakistan was 9.98 per 1000 (14.8 per 1000 in rural areas, 7.4 per 1000 in urban areas) and 7.0 per 1000 in Turkey (8.8 per 1000 in rural areas, 4.5 per 1000 in cities). The average age of onset of epilepsy in Pakistan was 13.3 years, and in Turkey it was 12.9 years. The distribution by seizure type in Pakistan and Turkey was respectively: generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) - 80.5 and 65.4%, focal - 5 and 7.4%, tonic and atonic - 5.8 and 3.7% , myoclonic - 5.8 and 1.2% [22].

The annual incidence of epilepsy in the pediatric population in Ethiopia is 64 per 100,000 [95% CI 44–84]. The frequency of GTCS is 69%, focal – 20%. In 22% of cases, a family history of epilepsy was noted [46].

The first signs of GE

Attacks of generalized epilepsy are completely sudden and impossible to predict. But there are some signs that have manifestations similar to epilepsy, but are not it. They are a consequence of the action of some exogenous factor that adversely affects the functioning of the central nervous system.

- Involuntary muscle twitching, including those that sometimes occur when falling asleep (so-called physiological twitches). Usually at this moment you dream that you stumble or fall from a small height, after which you suddenly wake up, sometimes even screaming.

- Sleep disturbances - nightmares, sleepwalking (sleepwalking) or sleep talking.

- Migraine and accompanying symptoms. It can begin with an aura, during which various perception disturbances occur: visual distortions (atrial fibrillation, flashes, distortion of objects, photopsia, narrowing of visual fields, temporary blindness, etc.), distortion of smell and taste (odors that actually no, a metallic taste appears in the mouth without visible bleeding of the oral mucosa), auditory hallucinations, nausea, numbness/tingling of the extremities.

- Characteristic manifestations of a panic attack are a feeling of fear, a feeling of approaching death, tachycardia, heavy rapid breathing and the feeling that you are watching what is happening as if from the outside.

- Atrioventricular block can be complicated by the occurrence of Morgagni-Adams-Stokes syndrome - fainting caused by a sharp decrease in cardiac output and brain hypoxia, resulting in breathing problems and convulsions.

- The following signs are characteristic of epilepsy - involuntary urination and biting the tongue during sleep. It is possible that the very first attack of generalized epilepsy occurred in a dream.

Epidemiology of childhood epilepsy in Russia

Epidemiological studies conducted in Moscow (1980–1981) showed that 4.4% of children had at least one convulsive episode; in 5.4% of cases, epilepsy was accompanied by mental retardation and mental retardation. The onset of the disease in 29.3% of cases in children is under 3 years of age, including 20.3% under 1 year. In the case of a malignant course of the disease in patients with mental retardation, seizures under the age of 3 years occurred in 44.9% of cases (up to 1 year - 37.3%). In 95.78% of cases, FS was observed in children in the first 5 years of life, of which 41.4% occurred under the age of 1 year [14].

The incidence of epilepsy in St. Petersburg was 1.56 per 1000 children. In children with epilepsy, the genetic nature of the disease was established in 81.9% of cases [6].

In the Novosibirsk region, a high incidence of epilepsy among children of primary and secondary school age is shown: 14.8 per 1000 children aged 7 to 13 years. The frequency of occurrence among boys prevailed over girls (61.1% versus 38.9%). The incidence of idiopathic epilepsy was 3.4 per 1000 children. FS was registered in 7.5% of children, more often in boys. The prevalence of cryptogenic and symptomatic forms has been noted [4].

The prevalence of childhood epilepsy in Saratov was 2.7 per 1000 children. Focal forms of epilepsy were diagnosed in 55% of cases, generalized - in 45% of cases. Among the symptomatic focal forms, temporal lobe (23.8%) and frontal (16.7%) epilepsy predominated. Among the idiopathic focal ones is rolandic epilepsy (60%). The leading risk factors for epilepsy in children were: hereditary burden, perinatal hypoxic-ischemic damage, cerebral dysgenesis. Cryptogenic forms accounted for 57.3% [7].

The prevalence of epilepsy in rural areas of the Volgograd region was 2.84 per 1000 children (among males - 3.4 per 1000, among females - 2.36 per 1000). Etiological factors: perinatal pathology (46%), traumatic brain injury (20.7%), family history of epilepsy (11.%), neuroinfections (6.7%). Focal seizures were recorded in 56.0% of cases, generalized seizures - 39.4% [3].

The incidence of epilepsy in the Republic of Tatarstan was 1.0 per 1000 population of children from 0 to 14 years old and 1.1 per 1000 adolescents from 15 to 18 years old. The prevalence of epilepsy among children aged 0 to 14 years was 5.4 per 1000 population of the corresponding age and 7.0 among adolescents. In the structure of epilepsy and epileptic syndromes, focal ones predominated - 55.5%; generalized - 43%, unclassified forms of epilepsy - 1.5%. Idiopathic epilepsy was registered in 21.25%, symptomatic - 32.0%, cryptogenic - 46.75% [13].

In the Krasnoyarsk Territory, the prevalence of epilepsy is 2.8 cases per 1000 population: among children - 5.1 per 1000, adolescents - 6.1 per 1000, and among adults - 2.3 per 1000. Etiological forms of epilepsy: cryptogenic epilepsy (46 .2%), symptomatic (42.5%), and idiopathic (7.4%) epilepsy [15].

According to the results of research work carried out in the Republic of Tyva, which belongs to an area with a high prevalence of epilepsy and epileptic syndromes in children and adolescents, it was revealed that the incidence of onset of epileptic seizures occurred mainly in the age range from newborn to 5 years. The average standardized prevalence of epilepsy among the child population of the Republic of Tyva was 3.2 ± 2.9 [95% CI: 0.96 – 4.63] per 1000. Among the risk factors for childhood epilepsy, the most significant were: perinatal pathology, family history, neuroinfections [17].

Symptoms of generalized epilepsy

Based on the previously described types of GE, the following characteristic symptoms can be identified:

- convulsions of varying amplitude and frequency (from simple blinking to spasm of the whole body, followed by twitching of the limbs, with tongue biting and head injuries due to uncontrolled contractions of the neck muscles);

- absence seizures (blackouts);

- disorder of consciousness and memory - with simple seizures, some patients can describe their sensations during an attack, but in other cases they do not remember them. The more often the attacks occur, the faster dementia will occur;

- vegetative manifestations - redness of the face, increased breathing and increased blood pressure;

- the appearance of a migraine-type aura, as described earlier (which is more typical for secondary generalized epileptic seizures).

Diagnosis of generalized epilepsy

The Yusupov Hospital has a complex of modern equipment for a complete and in-depth examination of each patient who contacts our specialists with neurological pathologies. At the beginning of the diagnostic search, the hospital's neurologists will carefully collect anamnesis to determine the causes and nature of the attack. A single seizure does not constitute epilepsy, but its presence increases the risk of epilepsy. Throughout their lives, 11% of people have had at least one episode, but only 2-3% have epilepsy. The patient is asked whether there has been brain injury, infection, poisoning, seizures or cancer. It is important to know whether close relatives suffered from epilepsy or other neurological disorders. The doctor asks questions about cases where the first symptoms described above appear. An extremely important instrumental diagnostic method is electroencephalography (EEG), thanks to which epileptic activity can be detected. The most common options for displaying them:

- sharp waves;

- peaks (adhesions);

- “peak-slow wave” and “sharp wave-slow wave” complexes.

High-amplitude peak-wave complexes with a frequency of 3 Hz are quite often recorded during absence seizures. An EEG is done during the interictal period and, if possible, at the time of the attack.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is valuable in diagnosis, thanks to which it is possible to see the foci of brain damage that cause an epileptic attack. These could be tumors, aneurysms, or areas of sclerosis.

Institute of Child Neurology and Epilepsy

Issues associated with the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) in adults were studied in 114 adult patients. IGE accounted for 9.5% of all forms of adult epilepsy. The structure of IGE included the following forms of epilepsy: juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) - 42% (n = 48), juvenile absence epilepsy - 12% (n = 14), childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) - 8% (n = 9), IGE with an unknown phenotype - 38% (n = 43). Late diagnosis of IGE (maximum 68 years) was noted in 1/3 (n = 32) of patients. The main reasons for the late diagnosis of IGE were ignoring absences and myoclonic seizures (n = 21), and erroneous diagnosis of focal epilepsy (n = 16). The majority of patients in the study group received treatment with carbamazepine. This was the main reason for ineffective treatment and severe course of IGE. Drug-resistant epilepsy was diagnosed in 10% of patients. 75% of patients were in remission of epilepsy for 5-13 years, but continued to take antiepileptic therapy. Treatment was discontinued in 46 patients. The best results were obtained in patients with DAE (recurrence of attacks in one out of 6 patients). The least favorable results were obtained in patients with IGE with an unknown phenotype (recurrence of attacks - 60%). Satisfactory treatment results in adult patients with IGE (achievement of clinical remission) were obtained in 70% of cases, but discontinuation of treatment in these patients remains a serious problem.

Key words: idiopathic generalized epilepsy, adults, diagnosis, treatment.

The study of idiopathic generalized epilepsies (IGE) included 114 adult patients. The share of IGE cases was 9.5% of all forms of adult epilepsy. The structure of IGE was as follows: juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) - 42% (n= 48), juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE) - 12 (n= 14), childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) - 8% (n= 9 ), IGE with indefinite phenotype -38% (n= 43). Late diagnosis IGE (tach. - 68 years old) was identified for 1/3 (n= 32) of patients. The main causes of late diagnosis of IGE were a failure to recognize absences and myoclonic seizures (n= 21) or missed diagnosis of focal epilepsy (n= 16). The main cause of noneffective therapy or severe seizures was therapy with carbamazepine. Pharmacoresistant epilepsy was diagnosed in 10% of patients. Remission of 5 to 13 years was detected in 75% of patients, though those patients had still taking drugs (AED). The therapy was discontinued for 46 patients and best results were achieved in patients with CAE (seizures relapse appeared in 1 of 6 patients). The worst results were observed in patients with IGE indefinite phenotype (seizures relapse in 60% of cases). In general, satisfactory results of AED therapy (seizure remission) were achieved in 70% adult patients. However, discontinuation of AED therapy for those patients with IGE remains a problem.

Key words: idiopathic generalized epilepsy, adults, diagnostics, treatment.

As age increases in the population of patients with epilepsy, the proportion of patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsies (IGE) decreases, the absolute majority of which are characterized by an age-dependent onset; At the same time, the proportion of people suffering from partial symptomatic and cryptogenic forms of epilepsy (SPE) is increasing. Most forms of IGE have a favorable prognosis and high effectiveness of valproic acid preparations [1, 4, 5, 7, 8]. That is why the ratio of IGE/SPE, which is 40/60 in the pediatric population of patients, in the adult population changes in favor of the latter, amounting to 10-20/80-90, according to various data, which may be explained by the greater resistance of partial seizures to treatment, i.e. e. less likely to achieve remission [2]. However, a certain range of problems associated with IGE, often not resolved in a timely manner, persist for many years, sometimes for life.

In accordance with the data obtained during the work of the epileptology office of the KDO MONIKI, the proportion of patients with IGE from the total number of patients with epilepsy for the adult population of the Moscow region is 9.5%: a total of 114 people (48 women and 66 men) aged from 18 to 68 years with disease duration from 1.5 to 60 years (on average -16 years). Active epilepsy is observed in 30% (o = 38) of them, the remaining patients have drug remission of varying duration. The ratio of IGE forms is as follows: JME is 42% (o = 48), DAE - 8 (o = 9), juvenile absence epilepsy - 12 (o = 14), IGE with an unidentified (variable) phenotype - 38% (o = 43). The most common problems in this cohort of patients: unusually late onset of IGE, inadequate diagnosis of epilepsy in childhood, long-term inadequate therapy, pharmacoresistance of seizures, relapses of the disease after discontinuation of therapy, differential diagnosis with non-epileptic conditions.

Unusually late diagnosis of childhood and juvenile forms of epilepsy after 20 and even 30 or more years was noted in more than 30% of observed patients. Some of them actually had a relapse of a previously undiagnosed disease after a long spontaneous remission that lasted more than 5 years (n = 11).

Clinical example

Patient A., 30 years old. Complaints of repeated attacks within one year, with a frequency of 1-2 times a month, in the form of loss of consciousness and convulsions, occurring in the morning after waking up; an attack of convulsions is usually preceded by trembling of the hands. History of short, infrequent episodes of hand shaking at age 19-20 during military service, which spontaneously resolved without treatment. When conducting video-EEG sleep monitoring, typical changes characteristic of JME were revealed during falling asleep and awakening in the background: generalized high-amplitude flashes of peak- and polypeak-wave complexes with a predominance on the left appear, lasting from 1.5 to 3 s. Prescribed therapy with Depakine Chrono at a dose of 25 mg/kg led to a stable electro-clinical remission observed for 1 year. Perhaps, in this and similar observations, long-term clinical remission was not true, since the patient was not monitored for a long period of life, including EEG was not recorded. According to Panayiotopolus et al. (1991), despite clearly developed criteria for JME, the percentage of diagnostic errors remains high due to insufficient attention on the part of the patient and doctors to myoclonus and the variability of EEG patterns of this disease. The nonspecificity of EEG changes in JME in many cases and the characteristic identification of focal changes are emphasized by many researchers [1, 2, 5, 8].

Another part of patients with late diagnosed IGE (o = 32) are those cases where active epilepsy proceeded for many years and even decades under the guise of another form of the disease. In particular, typical generalized seizures (absences and myoclonic paroxysms) were often regarded and treated as partial. The main reason for this was the absence in the medical history of patients suffering from long-term IGE of differentiation into forms of epilepsy and types of seizures, the dominance of the wording “epilepsy” or “episyndrome”, “absence seizures”. The most ignored type of seizures by both patients and doctors were myoclonic seizures: arm myoclonus (n = 16) and eyelid myoclonus (n = 5) as part of JME and Jeavons syndrome. Almost all case histories contained defects in EEG recording and interpretation, or an EEG study was not conducted at all, or the EEG recordings were lost. Most patients in this group were treated with carbamazepine drugs in monotherapy or polytherapy, which is not only not justified, but can provoke attacks in IGE [1, 5, 8]. All this explains the unjustifiably late diagnosis of IGE, the lack of a differentiated approach to antiepileptic therapy, its inadequacy and, as a consequence, long-term persistence and the formation of intractable seizures.

Clinical example

Patient P., 31 years old. Onset of epilepsy at the age of 13 years with a generalized convulsive seizure (GSE), which developed suddenly after waking up. When visiting a doctor, a diagnosis of “epilepsy” was immediately established and treatment with finlepsin was prescribed, which was carried out continuously until the age of 31 with periodic adjustments of the drug dose (the maximum dose was 600 mg per day). Stereotypical GSPs were repeated exclusively after awakening with a gradual increase over time: from 1 time per month at the onset of the disease to dozens per month, and periodically - until daily attacks by the age of 29, when the patient turned to the Monica Children's Clinical Hospital. Upon examination, no disturbances in the mental, somatic and neurological status were noted. The presented EEGs—several short routine recordings (no more than 5 minutes)—did not contain typical patterns of epileptiform activity. The MRI of the brain corresponded to the normal variant. When conducting video-EEG monitoring during night sleep, normal background activity was recorded in combination with single short generalized high-amplitude peak-, double-peak and polypeak-slow wave discharges, which in the morning hours formed in more regular and prolonged bursts of up to 1.5 with a frequency of 3 Hz At the 1st and 2nd min. hyperventilation, synchronously with flashes, 2 episodes of upward eyeballs with rapid blinking were recorded (a typical absence pattern with a myoclonic component) (Fig. 1). At 20 minutes after awakening, a generalized convulsive attack of GSP developed synchronously with the EEG pattern of GSP.

Rice. 1. EEG of patient P., 29 years old. Against an unchanged background, periodically occurring bursts of generalized bilateral synchronous peak-slow wave activity with a frequency of 3-3.5 Hz, an amplitude of 250-300 μV and a duration of 3-5 s are recorded - a typical absence pattern.

Thus, the clinical picture and EEG characteristics were consistent with the diagnosis of JAE, which was manifested by DBS and typical absence seizures; The patient did not know about the presence of the latter. Finlepsin therapy was carried out for 16 years, which led to the formation of severe, intractable epilepsy. During therapy carried out for two years (first, Depakine Chrono at a dose of up to 3000 mg/day in monotherapy, then Depakine Chrono 3000 mg/day in combination with topiramate 300 mg/day), stable remission was not achieved. Against the background of the latest combination of AEDs (Depakine Chrono in combination with topiramate), rare GSPs remain, absence seizures are not observed.

We classified 13 (10%) cases as intractable or drug-resistant IGE (JAE - 2, JME - 3, IGE with an unknown phenotype - 8). As is known, a feature of IGE is the high sensitivity of attacks in all forms of epilepsy without exception to valproic acid drugs, with treatment of which remission is achieved in 70-75% and significant improvement in 20% of cases in patients of childhood and adolescence [1, 3, 4 , 5, 6]. For the treatment of intractable epilepsy with insufficient clinical effectiveness of valproic acid drugs used at the maximum dose, we used combination therapy, including valproate and topiramate (at a dose of 200-400 mg/day in 8 patients), valproate and levetiracetam (at a dose of ~ 3000 mg/day). day in 5 patients). The first combination made it possible to effectively control resistant myoclonic and heralized convulsive seizures, the second - all three types of seizures. It should be noted that the achievement of clinical remission in 7 patients of both groups did not correlate with electrical remission, which in most forms of IGE is often associated with an unfavorable prognosis and a high probability of seizure recurrence after discontinuation of antiepileptic therapy [1, 2, 8]. In three patients, a significant reduction in attacks was noted, but complete remission could not be achieved. The majority of patients with IGE (n = 75) who consulted an epileptologist had long-term clinical drug remission (more than 5 years, maximum 13 years), continuing to constantly take the prescribed therapy. An attempt to cancel treatment was made in most of them. The dose of valproate was reduced no faster than 250-300 mg once a month under the control of routine EEG recording. Unfortunately, it was not possible in all cases to conduct video-EEG monitoring before discontinuing therapy. We associate this with the recurrence of attacks in some patients who apparently did not have electro-clinical remission. There was no significant relationship between the stability of clinical remission after discontinuation of therapy and the duration of drug remission in various forms of IGE. The best results were found in patients with DAE. Relapse of HSP occurred in one of 6 patients when the dose of valproate was reduced by 50% of the original dose. Of the 8 patients with JAE, two had seizures resume in the first 6 months, and one - after 14 months. after discontinuation of treatment. In the remaining patients with an established diagnosis of JME and IGE with an undetermined phenotype, in 60% of cases, complete withdrawal of AEDs could not be achieved due to the resumption of seizures or the appearance of epileptiform activity on the EEG, recorded during the process of treatment withdrawal or in the first months after its completion. On average, the best results were achieved in patients in whom the presence of electro-clinical remission was confirmed by many hours of EEG monitoring. Our experience confirms that discontinuation of antiepileptic therapy in adult patients with IGE requires more careful EEG monitoring with step-by-step EEG monitoring both in the process of choosing therapy and when deciding to discontinue therapy and when gradually withdrawing drugs. Sometimes there was a need for differential diagnosis of IGE with somatic diseases.

Clinical example

Patient S., 68 years old. Diagnosis: childhood absence epilepsy. Status course of absence seizures. From the anamnesis it is known that at the age of 8-9 years generalized convulsive seizures debuted, which subsequently dominated the clinical picture of the disease throughout life. There was no indication of absence seizures in the anamnesis (perhaps the patient did not remember them). The frequency of attacks in adulthood was high - up to 7 or more attacks per month. For many years, the patient received treatment with diphenin (300 mg/day) and phenobarbital (300 mg/day). After 60 years, side effects (according to the patient) of antiepileptic therapy appeared in the form of disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, and therefore the dose of AEDs taken was halved and carbamazepine was added to the treatment at a dose of 300 mg/day. The frequency of HSP gradually decreased with age to 1-2 per year (it is possible that attacks occurred more often, but since the patient lived alone, they could go unnoticed). However, conditions appeared during which the patient became lethargic and lethargic for several days (from 3 to 7), practically did not get out of bed, did not eat, and contact with her was difficult. The conditions were regarded as manifestations of dyscirculatory encephalopathy. The prescribed vascular therapy was ineffective. The states were interrupted suddenly, just as they developed. After the patient contacted an epileptologist at KDO MONIKI, an electroencephalographic study was performed, which revealed almost continuous generalized bilateral synchronous high-amplitude peak-wave activity with a frequency of 3 Hz - a pattern of typical absence seizures (Fig. 2) . Remission of absence seizures was achieved during therapy with Depakine Chrono at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day.

Rice. 2. EEG of patient S., 68 years old. Throughout the entire recording epoch, frequent and almost continuous (every 3-5 seconds) bursts of generalized bilateral synchronous peak-slow wave activity with a frequency of 3-3.5 Hz are recorded in the background - a pattern of the status of typical absence seizures.

In general, IGE therapy in adult patients, despite the transient difficulties and shortcomings of previous treatment, can be assessed as highly effective. Satisfactory control of attacks is achieved in 70% of cases, however, the prognosis regarding the prospect of discontinuation of therapy in most cases remains quite serious.

Bibliography

1. Mukhin K.Yu., Petrukhin A.S. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy: systematics, diagnosis, therapy. – M.: Art-Business Center, 2000. – P. 285-318. 2. Mukhin K.Yu., Petrukhin A.S., Glukhova L.Yu. Epilepsy. Atlas of electro-clinical diagnostics - M.: Alvarez Publishing, 2004. – P.202-240. 3. Petrukhin A.S. Epileptology of childhood: a guide for doctors. - M.: Medicine, 2000. – P. 44-62. 4. Janc D. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy // In: Dam M., Gram L. (eds). Comprehensive epileptology - New York: Raven Press, 1991. - P. 171-185. 5. Loiseau R. Childhood absence epilepsy // In: Roger J. et at (eds) Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence - London: Libbey, 1992. - R. 135 -150. 6. Panayiotopolus S.R., Tahan R., Obeid T. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: Factors of error involved in the diagnosis and treatment // Epilepsia - 1991. - Vol. 32. - R. 672-676. 7. Panayiotopolus S.R. The epilepsies. Seizures, syndromes and Management. - Blandon Medical Publishing, 2005. - P.271-349. 8. Thomas R. Genton R. Wolf R. // In: J. Roger et al. (eds) Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence - London: Libbey, 2002. - R. 335-355.

Prognosis of generalized epilepsy

Epilepsy is still a particularly important pathology that radically changes the life of the person diagnosed with it. At our level of medicine, a cure for this disease has not yet been found; a number of restrictions are imposed on the patient: he cannot drive a vehicle, he should avoid places with unexpected flashes of light. The ability to work of these individuals depends on the frequency and timing of attacks. It is prohibited to work near fire, at heights, in burning workshops, near moving machinery, as well as activities that require quick reaction and attention.

No less important is the problem of stigmatization. Correct therapy with antiepileptic drugs increases the interictal period. The prognosis depends on the form of GE. Idiopathic is the most favorable, since it is not accompanied by mental disorders. Symptomatic completely depends on the disease that caused it. But with the right therapy, it is possible to significantly improve the patient’s quality of life and minimize the number of seizures.

The Yusupov Hospital has many years of experience in treating this disease, which will help choose an individual approach to each patient with epilepsy so that he can lead a normal life even with such an illness. It is necessary to follow all instructions from your doctor and not skip medications to avoid worsening the condition.