Migraine in women

Migraine is a disease that is significantly more common in the female population: the ratio of the prevalence of migraine among men and women of reproductive age is 1:2–1:3. Changes in hormonal status associated with menarche, pregnancy, lactation and menopause are often accompanied by changes in the nature and frequency of migraine attacks. Thus, female sex hormones determine strict correlations between headache frequency and the menstrual cycle.

Menstrual migraine

Menstrual migraine is a common form that occurs in more than 50% of migraine patients. Typically, menstrual migraine is characterized by more severe and prolonged attacks, lasting several days. This leads to significant maladaptation of young women: they cannot go to work or their performance is significantly reduced, they cannot devote enough time to family and personal interests. However, menstrual migraine is underdiagnosed by neurologists, gynecologists, and general practitioners. This is largely due to the fact that the patients themselves do not complain of headaches, as they consider it a manifestation of premenstrual tension syndrome.

The International Classification of Headaches distinguishes two types of menstrual migraine - true menstrual migraine without aura and migraine without aura associated with menstruation (Table). True menstrual migraine is observed in 7–19% of patients [9, 10].

The menstrual cycle and migraine

Normally, hormonal fluctuations associated with the menstrual cycle are regulated by the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Thus, the influence of the activity of the hypothalamus on the activity of the pituitary gland is carried out through gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GHR), the secretion of which is regulated by various neurohormonal substances - norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, endorphins, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), corticosteroids. It is known that norepinephrine has a stimulating effect in this case, and opioids, corticosteroids and CRH suppress the secretion of GnRH. GnRH, in turn, regulates the secretion of pituitary gonadotropins - follicle-stimulating and luteinizing hormones, which are necessary for the secretion of hormones by the sex glands. Androgens and estrogens are also involved in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion, providing a feedback mechanism. The development of menstrual migraine is associated with two factors:

- with an increase in the content of prostaglandins in the endometrium and systemic circulation in the luteal phase of the cycle with a subsequent increase during menstruation;

- with a sharp drop in estrogen and progesterone levels in the late luteal phase of the cycle.

A comparison of the profile of fluctuations in the level of hormones that determine the normal menstrual cycle and the onset of menstrual migraine convincingly proves that a drop in estrogen levels in the late luteal phase of the cycle is, if not the cause, then a powerful provocateur of the development of a migraine attack. This clinical observation is supported by experimental data. It was shown that the administration of progesterone in the premenstrual period delayed the onset of menstruation in women, but did not affect the occurrence of a migraine attack; on the contrary, the administration of estrogen did not affect the timing of the onset of menstruation, but significantly delayed the onset of a migraine attack [17, 18]. Thus, the key factor that ensures the onset of a menstrual migraine attack is a drop in estrogen levels.

A series of experimental studies have shown that both progesterone and estrogen can influence cortical hyperexcitability, the main pathophysiological mechanism of migraine, through activating neurotransmitters (glutamate) and inhibitory neurotransmitters (gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)). In particular, estradiol has been shown to increase the activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors and also reduce the synthesis of GABA [11]. Progesterone, on the contrary, has an inhibitory effect, potentiating GABA-mediated neurotransmission. Both estrogen and progesterone influence cortical spreading depression (SCD), which underlies the development of migraine attacks. Exposure to both hormones increases both the frequency and amplitude of RCD, whereas exposure to estrogen alone lowers the threshold for the occurrence of RCD. It is assumed that estrogen affects the activity of genes encoding molecules of substances that trigger and support the development of RCD [20].

Moreover, the effects of ovarian steroids on the trigeminovascular system have been shown. The fall in estradiol in the late luteal phase of the cycle leads to a significant increase in the expression of neuropeptide Y, which modulates both the conduction of pain impulses and vascular tone. A sharp change in the activity of neuropeptide Y, associated with a drop in estrogen levels, can trigger a migraine attack [13]. On the other hand, high estrogen levels correlate with higher pain tolerance. Thus, the administration of estradiol and progesterone to female rats after ovarectomy demonstrates a significant increase in pain thresholds in response to electrical stimulation [4]. The presence of a dense network of estrogen receptors in the cerebral cortex, limbic system, hypothalamus and other formations involved in the pathogenesis of migraine attacks: periaqueductal gray matter, monoaminergic nuclei and trigeminal nucleus of the brainstem, which determines the regulatory influence of estrogens on genomic, intracellular signaling and other processes of neuroplasticity. The stimulating effects of estrogens on the formation of growth factors (neurotrophins), primarily the brain-derived neurotrophic factor BDNF, are well known.

Estradiol has a modulating effect on neuronal excitability, changing the plastic properties of axon terminals and receptors. In particular, the administration of estradiol to experimental female rats is accompanied by an increase in the density of the spiny apparatus on the lateral branches of the apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus, populated by NMDA receptors, which increases the level of glutamatergic activity [1, 2]. Estradiol has the ability to activate glutamatergic transmission through allosteric stimulation of NMDA receptors. In addition, estradiol reduces the neuroinhibitory effect of GABA by inhibiting the activity of glutamate decarboxylase. Multiple effects of estrogen within the serotonergic system are known: an activating effect on the synthesis of serotonin and an inhibitory effect on its enzymatic metabolism [3].

These data are confirmed by clinical observations, where pain perception was studied in women with chronic pain syndromes over several menstrual cycles. A significant increase in pain perception was obtained in the first five days compared to other days of the cycle [6]. Healthy women also experience decreased pain thresholds during the premenstrual and menstrual phases of the cycle [14].

Clinical picture of menstrual migraine

Menstrual migraine is characterized by the development of migraine attacks, most often without aura, characterized by a duration of 4–72 hours (untreated), the presence of two of the following characteristics: unilateral localization, pulsating nature, moderate to severe pain intensity, worsening of headache after normal physical activity (for example, walking), as well as one of the accompanying symptoms (nausea and/or vomiting, sensitivity to light or sound). To make a diagnosis of migraine, at least five such attacks are required, as well as the absence of other causes causing these disorders.

In outpatient settings where time is a concern, practitioners may use a menstrual migraine screening questionnaire to assist in diagnosis. The patient is asked three questions:

- Do you have headaches associated with your menstrual cycle (occurring between two days before and three days after your period) most of your menstrual cycles?

- Are your cycle-related headaches significantly worse than usual?

- When you develop headaches related to your menstrual cycle, do lights irritate you more than usual?

Menstrual migraine can be suspected if the answers to the first question and one of the subsequent ones are positive. The sensitivity of this test is 0.94, specificity is 0.74 [19].

Unlike migraine not associated with menstruation, menstrual migraine is characterized by greater severity of attacks, longer duration, greater maladaptation and resistance to standard therapy.

Management of patients with menstrual migraine

A feature of the management of patients with menstrual migraine is the extreme importance of keeping a headache diary. The purpose of keeping a diary is to establish a connection between the development of migraine attacks and the onset of menstruation, to identify the frequency of attacks, and to determine the pattern of prescribing preventive treatment. For three months, the patient should fill in the diary for the days of menstruation (for example, with the symbol “0”), the days of migraine headache (for example, with the symbol “X”), the days of non-migraine headache (for example, with the symbol “+”) (Fig.).

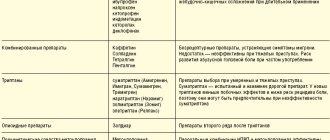

Treatment of patients with menstrual migraine consists of pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods and includes two areas - relief of attacks and their prevention. Relief of an attack of menstrual migraine is carried out according to the same principles as relief of an attack of non-menstrual migraine. To relieve an attack, drugs from the following pharmacological groups can be used:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): ibuprofen (400 mg), acetylsalecylic acid (Aspirin) (1000 mg), diclofenac (25–50 mg)). In the presence of nausea and/or vomiting, as well as to enhance the effect of NSAIDs, it is recommended to combine them with antiemetics (metoclopramide (10 mg), domperidone (10 mg)).

- Ergotamine preparations (Sincapton, Dihydrergot).

- Triptans are specific anti-migraine drugs, agonists of 5HT1B/1D serotonin receptors (sumatriptan (100 mg), zolmitriptan (2.5 mg), eletriptan (40 mg)).

When selecting a drug, the following recommendations must be taken into account: analgesics and NSAIDs should be used for moderate attacks, no more than 10 days a month. If drugs in this group do not stop the attack completely, then it is necessary to prescribe triptans or ergotamine drugs. It is necessary to avoid taking drugs from the group of combined analgesics, especially those containing opiates, barbiturates, and caffeine, since taking these drugs significantly increases the risk of developing drug-induced or abuse headaches. Numerous studies have shown that triptans are most effective for relieving menstrual migraines. It is necessary to recommend that the patient use drugs in an adequate dose and at the beginning of the attack, when the headache has not reached its maximum [3].

Prevention of menstrual migraine

Standard preventive pharmacotherapy can be used in patients with menstrual migraine in cases where there are also frequent attacks not associated with menstruation, as well as in cases of resistance. The following drugs can be prescribed: topiramate (100 mg/day), amitriptyline (100 mg/day), propranolol (40–80 mg/day), verapamil (40–80 mg/day). In addition to standard therapy, magnesium preparations (360 mg/day) can be used to prevent menstrual migraine.

Another form of prevention for menstrual migraines is hormone therapy. The effectiveness of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) and estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) is discussed. The use of COCs is most suitable for women who need contraception, as well as patients with heavy bleeding, severe dysmenorrhea, and endometriosis. It must be remembered that prescribing COCs to patients with migraine with aura increases the risk of stroke, therefore, before starting hormonal therapy, it is necessary not only to diagnose the form of migraine, but also to make sure that there are no other risk factors for stroke, and that the patient is not a smoker. As a rule, monophasic drugs containing 35 mg or less ethinyl estradiol are used (in most low-dose COCs, the estradiol content ranges from 20 to 35 mg). Patients who do not require contraception are prescribed low-dose estrogen at a dose of 0.9 mg/day, which can be in either tablet or transdermal form [7, 8].

Since with menstrual migraine it is almost possible to accurately predict the onset of the next attack, such a direction of therapy has appeared as short-term prophylaxis, which is prescribed two days before the expected menstruation for 5-7 days of daily use. For the purpose of short-term prevention, drugs of several pharmacological groups are used: NSAIDs, estrogen-containing drugs, triptans.

Non-pharmacological methods of treating menstrual migraine include psychotherapy (cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, feedback), patient education, correction of risk factors (diet, sleep hygiene, external factors, increasing stress resistance). Various methods of physiotherapy can be used - acupuncture, therapeutic exercises, massage. General recommendations may be the choice of a qualified specialist to carry out non-drug treatment, while the patient must be motivated to carry out such therapy; these methods can be used as basic methods or in addition to medication.

Pregnancy, lactation and migraine

According to clinical observations, 60–70% of women suffering from migraine note a significant improvement in the course of the disease during pregnancy, especially in the second and third trimesters, which is apparently associated with stabilization of estrogen synthesis. In a menstruating woman, the corpus luteum synthesizes progesterone and estradiol for 14 days. At 10–12 weeks of pregnancy, the placenta secretes progesterone and estradiol in concentrations sufficient to support pregnancy. There is a clear relationship between the increase in estrogen levels during pregnancy and a decrease in the frequency of attacks: in the first trimester, a decrease in migraine attacks is observed in 47% of patients, in the second trimester - in 83%, in the third - in 87%. Complete remission occurs in 11% of patients in the first trimester, in 53% in the second and in 79% in the third [15]. It should be noted that this pattern is typical for migraine without aura and does not apply to migraine with aura [5].

For practicing physicians, the question is always important what medications for the prevention and relief of migraine attacks can be recommended to patients with migraine during pregnancy and lactation. When selecting therapy, it is always necessary to remember that any prescribed pharmacological drug (with the exception of iron and folic acid supplements) may carry a potential risk for the fetus and newborn. However, there is evidence of the relative safety of low therapeutic doses of the following drugs:

- in the first trimester: paracetamol, ibuprofen, Aspirin, domperidone, metoclopramide, propranolol;

- in the second trimester: paracetamol, ibuprofen, aspirin, domperidone, metoclopramide, propranolol, amitriptyline, verapamil;

- in the third trimester: paracetamol, domperidone, metoclopramide, propranolol, verapamil;

- during lactation: paracetamol, ibuprofen, domperidone, metoclopramide, propranolol, verapamil.

When managing patients with migraine during pregnancy and lactation, the emphasis should be placed, first of all, on non-drug treatment: patient education with elements of psychotherapy, control of provocateurs, adherence to diet, sleep, rest and physical activity.

Migraine and menopause

During the perimenopausal period, most migraine patients also experience a change in the course of their migraine. During menopause, the secretion of progesterone and estradiol by the ovaries stops, and a period of hormonal stabilization begins [16]. In 67% of patients, the frequency of migraine attacks decreases by half or more, in 9% the frequency of attacks increases, in 24% the pattern of migraine does not change [12]. Treatment of migraine during the perimenopausal period follows the same principles as migraine in general, with the exception of the possibility of prescribing hormone replacement therapy.

Literature

- Tabeeva G.R. Menstrual migraine // Ross. honey. magazine 2008, vol. 16, no. 4, p. 195–199.

- Tabeeva G.R. Gromova S.A. Estrogens and migraine // Neurological journal. 2009. No. 5, p. 45–53.

- Tabeeva G. R. Menstrual migraine // Materials of the All-Russian scientific and practical conference with international participation “Headache 2007”. pp. 19–30.

For the rest of the bibliography, please contact the editor.

Yu. E. Azimova , Candidate of Medical Sciences G. R. Tabeeva , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

First Moscow State Medical University named after. I. I. Sechenova , Moscow

Contact information for authors for correspondence

general information

According to statistics, at least every tenth person on the planet suffers from migraine.

Women get sick approximately twice as often as men. This is associated with cyclical hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle. Typically, the disease makes itself felt before the age of 30-35; cases of the pathology occurring in childhood have also been described.

The biomechanism of the development of the disease is not precisely known. There are several theories about the occurrence of pain and accompanying symptoms, the most popular of which is neurovascular. According to this point of view, migraine begins against the background of activation of the trigeminal nucleus, which first causes spasm and then dilation of cerebral vessels. As a result, the tissue around the arteries becomes swollen, which leads to pain. In addition, the pathological process is associated with impaired serotonin metabolism.

Some scientists believe that pain occurs solely against the background of a sharp spasm and subsequent relaxation of blood vessels, resulting in tissue swelling (vascular theory). It has been clearly proven that the risk of developing the disease is significantly higher in women, as well as in people whose parents or close relatives also suffered from migraine.

Make an appointment

Causes

Migraine occurs against the background of various external and internal causes (triggers), each of which can cause another attack:

- mental and psycho-emotional stress;

- constant severe stress;

- sleep disturbances, insufficient rest at night;

- chronic fatigue (mental and physical);

- smoking;

- previous head injuries (even many years ago);

- excessive physical activity for a particular person;

- hormonal surges: puberty, menstruation (“menstrual migraine”), pregnancy;

- consumption of foods containing tyramine (chocolate, coffee, citrus fruits, nuts, cheese, smoked meats);

- drinking alcohol, especially low-alcohol drinks;

- sharp fluctuations in atmospheric pressure, changes in air temperature;

- overstrain of the senses: sharp sound, bright light, strong unpleasant odor, etc.;

- staying in a hot or stuffy room, etc.

Each person has his own “dangerous” factors. Most of them can be calculated and, if possible, avoided in the future.

Symptoms

A migraine attack follows a standard scenario, consisting of several successive stages.

- Prodromal (initial) stage. A person’s mood begins to change, yawning and drowsiness appear, or, conversely, insomnia. Some report sensitivity to noise and bright light. Sometimes there is a slight numbness in one of the hands. For most patients, these symptoms are enough to know that a full-blown migraine attack is on the way. The duration of the prodromal stage ranges from several hours to several days; it is not present in all patients.

- Aura. Occurs against the background of cerebral vascular spasms. Most often it manifests itself in the form of visual disturbances (flashes in the form of spots, zigzags or lightning in front of the eyes, distortion of the contours of objects, loss of individual fields of vision). Less common are taste or hearing disorders, problems with coordination of movements, etc. Aura is not observed in all patients.

- Actually a migraine attack. In most cases, it manifests itself as a unilateral headache that is pulsating in nature. It starts with slight discomfort and gradually gains strength, becoming simply unbearable. Movements, changes in body position, bright lights and loud sounds intensify the sensations, which is why patients try to spend this time lying in a darkened room. Against the background of a headache, many patients report nausea, vomiting, soreness in the muscles of the neck and shoulders, nasal congestion, lacrimation, chills and even fever. The duration of the attack is individual and ranges from 2-3 hours to several days.

- Resolution stage. At this time, the headache goes away on its own or after taking medications. Many patients fall asleep at first, but within 24 hours after the attack they may feel weak, lethargic, dizzy, and depressed. Increased sensitivity to light, sounds and smells also does not go away immediately. Less common is the opposite type of resolution stage, in which patients note increased activity.

Types of pathology

Migraines are most often classified according to the presence of an aura and its type. The following types of disease are distinguished:

- classic migraine: before an attack of pain, a typical aura occurs with visual, auditory, olfactory and other disturbances;

- migraine without aura: symptoms appear suddenly against a background of relative well-being; the rest of the clinical picture is characteristic of the disease.

Depending on the predominant symptoms, the following types of migraine are distinguished:

- ocular (ophthalmic): accompanied by classic visual impairments: glare, flickering, flare in certain areas of the visual field;

- retinal: the disease manifests itself as complete or partial loss of vision in one eye due to impaired blood circulation in the vessels of the retina;

- ophthalmoplegic: manifested by double vision, visual distortions, drooping of the eyelid;

- basilar: accompanied by dizziness, ringing in the ears, unsteadiness when walking, blurred speech;

- hemiplegic: characterized by loss of sensation and impairment of motor function of one arm or arm and leg on one side;

- cervical: occurs against the background of impaired blood flow in the vertebral arteries and is accompanied by a very severe headache;

- aphasic: pain is accompanied by speech disorders, as with a stroke;

- abdominal: additionally manifests itself as severe pain throughout the abdomen, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting; this form is very common in children;

- “decapitated”: the patient does not feel a headache, as a rule, only visual disturbances are noted, while the prodromal period and aura occur typically.

Migraine status stands apart. This is a severe condition in which two or more attacks occur in a row with less than 4 hours between them. This type also includes pain that lasts for more than 3 days. Against the background of migraine status, the patient experiences repeated vomiting, which does not allow him to eat, drink, or take medications normally.

No seizures

Hormonal therapy helps make attacks less frequent and milder, but does not always completely eliminate headaches.

Therefore, the treatment regimen also includes specific migraine medications - triptans. They suppress an attack by acting on the very mechanism of its development. Today these are the most effective remedies for migraines.

Despite the fact that medicine has many other painkillers - simple and combined analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs - they are not able to cope with menstrual migraine.

Article on the topic

Pain, I will eat you! What foods have pain-relieving properties?

Diagnostics

The patient's headache has characteristic features that immediately suggest a migraine. For diagnosis, the doctor uses the following methods:

- collecting complaints and medical history to determine the nature of the pain; special attention is paid to: the time of onset and end of the attack;

- provoking factors;

- nature of pain;

- the absence or presence of an aura, its symptoms;

- well-being after an attack;

If necessary, additional examinations and consultations with specialists are prescribed. The diagnosis of migraine is made by exclusion when no other causes of headache have been identified.

Make an appointment